PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

This collection published 2009 Copyright Rohini Chowdhury 2009 The moral right of the author has been asserted ISBN: 978-0-143-10054-6 This digital edition published in 2016.

PREFACE

Imagine sitting down to write the story of your life.

PREFACE

Imagine sitting down to write the story of your life.

Where would you begin, what incidents and experiences would you promote, which dark moments would you conceal, and how would you make your tale appealing to readers from times and places unknown? Such a task would challenge any writer, and most of us today would begin by scouting around to see how others had done it beforelooking for a model to follow, an example to emulate. But imagine undertaking such a task if there was no model, when nobody had done it before (at least, in a language that you could read), and where all that lay before you was the blank page; how would you set about tracing the contours of your life with nothing but your memories as guides? These questions are meant to emphasize the novelty of Banarasidass chosen narrative mode of autobiography in a literary tradition which rarely thought in terms of personal histories; but they are foolish questions, because they take no account of the differences in outlook between our lifetime and that of Banarasi nearly four centuries ago. He probably shared few of the motivations that might tempt a 21st-century author into autobiography: certainly, the cult of the individual that features so prominently today would have seemed almost as exotic to Banarasi as our blithe expectation of a continuously smooth progress down the path of everyday life. Being, among many other things, a theologian with works of Jain metaphysics to his credit, Banarasi perhaps saw his own life story as nothing more or less than a convenient source of illustrations to help explain the meaning of human existence and to illustrate the interplay of suffering and contentment in the world. Though he has moments of proud introspection in which he lists his achievements as a scholar, or describeswith almost palpable reliefhis return to the Jain fold after a period in a personal wilderness, his primary intention is not to promote himself, but rather to observe how a man must suffer the effects of his own past deeds, riding out storms in times of trouble and avoiding complacency in times of calm. Almost everyone who writes about Banarasi mentions his candour, for he was as quick to confess the mistakes and follies of his life as he was to boast of his accomplishments.

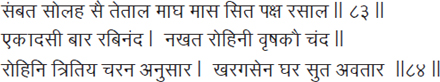

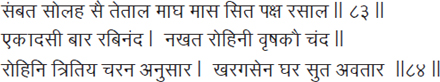

Ever the businessman, he offers a neatly balanced tally of faults and merits at the end of his tale, leaving the reader satisfied that the account is settled and has been told with honesty and a certain objectivity of viewpoint. But a close reading of Banarasis poetry shows also that his many gifts included a certain slyness, a skill at leaving things implied between the lines. An example of his deliberate and knowing deployment of facts in the narrative is his account of his own birth.  In Samvat 1643,

In Samvat 1643,

In the bright half of the month of Magh,

On the eleventh day, a Saturday

When the Moon was in Taurus and the reigning nakshatra Rohini

Was in the third quarterin Kharagsens house a son was born. Such an account, especially when ripped from its context in the body of the poem, may at first seem unremarkable: after all, it is a commonplace of Indian dating systems that individual days be specified not only in terms of the annual (solar) calendar but also the monthly (lunar) one. Following this convention, therefore, Banarasi declares that he was born on the eleventh day of the bright half of the winter month of Magh, the phrase bright half sita paksha indicating the fortnight when the moon was waxing, growing brighter.

But the poet goes beyond the bare outline of these conventional dating data by adding further astrological informationa rare level of detail in literary calendarsand in so doing builds up a prolonged crescendo climaxing in the triumphant announcement a son was born! Elsewhere in the Ardhakathanak, Banarasi describes many life-cycle events such as births and deaths: but nowhere else does he give us such an elaborate anticipation as this one celebrating his own appearance in the world. And he is not finished yet: in a further detail that may escape a hurried reading of the text, Banarasi locates the day of his birth in verse 84, cleverly alluding to one of the most sacred numbers in Indian numerology and thereby bringing a very special aura to the description of his incarnation (avatara) on earth. There are many other such literary tricks up the poets sleeve. In another beautiful allusion that also goes unnoticed by the commentators, Banarasis uniquely appealing account-sheet of qualities and faults that concludes the text is a delightfully cunning use of the literary trope known as solah shringara listing of the sixteen adornments which conventionally describe the plural perfections of the idealized literary heroine. While the qualities of such a lady may be lovingly listed in references to a set of physical attributes (such as lotus-eyes, slender waist, broad hips) or abstract ones (sensitivity, musicality of voice, tenderness of character), Banarasi distinguishes himself with a

In Samvat 1643,

In Samvat 1643,