Table of Contents

An Amaltas tree in full bloom in Delhi summer Photo: Rachit Dhawan

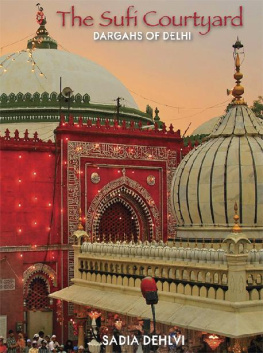

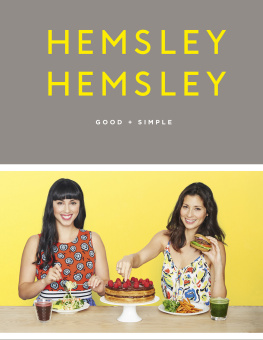

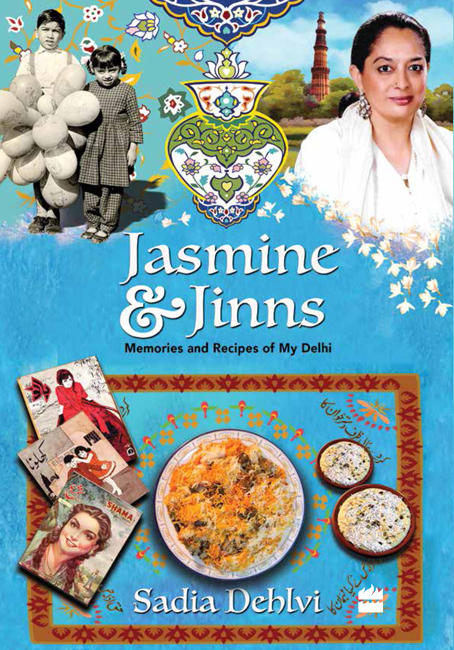

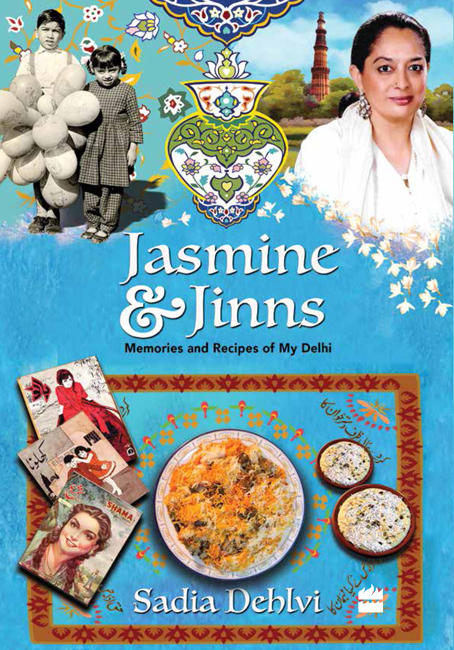

JASMINE AND JINNS

Memories and Recipes of My Delhi

SADIA DEHLVI

Photographs

Omar Adam Khan

For

Amma, Abba, Nani, Daddy, Ammi, Apa Saeeda, Mamoo Abdullah

and my extended Dehlvi family

and all those for whom Dehli is a way of life

Photo: Mayank Austen Soofi

Contents

An iftaar at the dargah of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya

In the name of Allah Most Merciful Most Compassionate

The best amongst you are those who feed others and offer greetings of peace to those whom you know and those whom you do not know.

Prophet Muhammad

Traditionally, family recipes were never shared with outsiders but just passed on from mother to daughter. Some of my aunts took offence on being asked for recipes. Decades ago, I remember a guest insisting that my aunt tell her the recipe of the nihari she had served. Avoiding the request, she offered to send the family the preparation whenever they wished. The lady remained adamant, saying it would not be right to impose frequent requests. Reluctantly, my aunt gave the recipe, which the lady hurriedly noted. After the visitor left, I expressed surprise at her large heartedness. With a mischievous smile she retorted, I am not so foolish. I did not reveal one main ingredient! She can never make it taste the way I prepare nihari.

Withholding a key ingredient is a standard trick deployed by many women and professional cooks. In yesteryears, a womans worth was pretty much valued by housekeeping skills, and cooking played a large role. When the menfolk went to work, womens lives revolved around the kitchen.

Initially, I anticipated problems in getting my aunts to share their cooking secrets. Instead, I found them willing and excited. Age has caught up with them and some are no longer around. Fortunately, they have passed on their culinary secrets to their daughters, and some to their daughters-in-law. Given the modern sharing culture, the younger lot happily gave me some of these recipes.

I had a wonderful time writing this book as it connected me to relatives whom otherwise one meets mostly at family weddings and funerals. I enjoyed visiting the homes of aunts and cousins, and they all fed me their delicious specialties.

Jalebi: A popular Indian sweet

I am particularly grateful to my amazing cousins Qurratulain, Farah, Asiya and my aunts Khala Rabia and Choti Auntie Ameena for helping me with recipes over the years. When cooking something that I wasnt confident about, I sought their advice. God bless the souls of Amma, Abba, Nani, Mamoo Abdullah and Apa Saeeda, from whom I learnt much more than just about food. I remain indebted to Ammi, my mother, for her constant criticism and I hope someday she approves of my cooking! I am sharing these recipes as an effort to preserve my Dehli that is fading away.

I cooked all the recipe dishes which were photographed at home. Apart from the goolar, kachnar bharta and sangri salan, which I made for the first time, all other dishes are cooked regularly in my kitchen. I hope you try these recipes and that they bring cheer to your table.

All the new photos unless specified otherwise have been taken by Omar Adam Khan. I thank him for these wonderful photographs that make this book as much his as mine. Thank you Sidrah Fatma Ahmed for helping with all the photo shoots.

I thank Vaseem, my brother, and Himani, my sister-in-law, for their indulgence and support. Immense gratitude to Mayank Austen Soofi, the official taster at home, for his suggestions at various stages of the manuscript. Thank you Jojy for typesetting all my books and helping design the pages. I thank Shreya Punj of HarperCollins for her dedication. Thank you Shaaz for your tireless efforts in creating the cover. I remain grateful to Karthika V.K. for accompanying me on my journey as an author. From the depths of my heart, I thank all those who bless my table by sharing meals at my home.

Khari Baoli Spice Market in Delhi

Little is known about Delhis food culture before the arrival of the Delhi sultans in the twelfth century. These sultans belonged to warrior clans of Central Asia, where food was more about survival than sophistication. The refinement in their cuisine came through interactions with local Indian communities and the abundance of fruits, vegetables and spices available here. The tables of Qutubuddin Aibak, Iltutmish and Razia Sultan consisted of meat dishes, dairy products, fresh fruits and varieties of local vegetables.

The fourteenth-century poet and historian Amir Khusrau wrote of the tables of Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq which consisted of about 200 dishes. The royal kitchen fed about 20,000 people daily. In his famous Persian Mathnawi Qiran us Sadain, the epic poem that later came to be known as Mathnavi dar Sifat-e-Dehli for its glorification of Delhis culture, Khusrau writes, The royal feast included sharbet labgir, naan-e-tanuri, sambusak, pulao and halwa. They drank wine and ate tambul after dinner. He describes the addition of two varieties of bread, naan-e-tunuk, a lighter bread, and naan-e-tanuri, bread baked in a tandoor. In addition, Khusrau mentions delicacies such as sparrow and quail, along with a variety of sharbet made from roses, pomegranates, oranges, mangoes and lemons.

In the Travels of Ibn Battuta in Asia and Africa, translated by Gibb, Ibn Battuta describes a royal meal at the table of the early fourteenth century Sultan Ghiyasuddin at Tughlaqabad as a lavish spread comprising thin round bread cakes; large slabs of sheep mutton; round dough cakes made with ghee and stuffed with almond paste and honey; meat cooked with onions and ginger; sambusak that were triangular pasties made of hashed meat with almonds, walnuts, pistachios, onions, and spices placed inside a piece of thin bread fried in ghee, much like the samosa of today; rice with chicken topping; sweet cakes and sweetmeat for dessert.