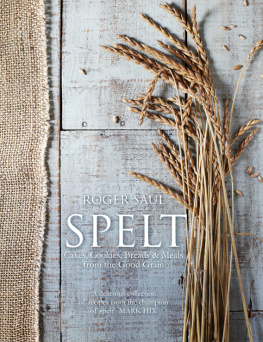

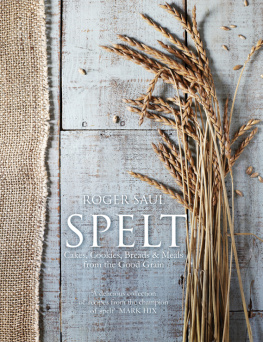

SPELT

SPELT

CAKES, COOKIES, BREADS & MEALS FROM THE GOOD GRAIN

ROGER SAUL

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Why dont you grow spelt? suggested my sister Rosemary as we sat in the kitchen of Sharpham Park. It was 2003, and my wife Monty and I had just bought the farmland around our lovely old abbots house, where we had lived for 26 years, and were trying to decide what we should grow.

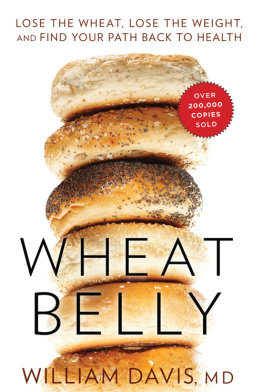

Rosemarys doctor had advised spelt as a gentle but nourishing alternative to conventional wheat. She was undergoing cancer treatment at the time and wanted to find foods that would boost her health and support her fragile body during treatment. What she said made me curious, and I set about researching the grain on the internet.

Spelt, I discovered, has ancient beginnings and potentially significant health benefits. It was virtually unheard of at the time, and my visits to health-food stores turned up small, dense and dull-tasting loaves on the top shelf, and some only slightly more tasty crackers. There were no growers in the UK at the time, so I set out to find and buy seed in France, Italy and Germany (my trading languages coming in handy from my days establishing and running the Mulberry designer brand!). In French, spelt is called lepeautre, in Italian, farro and to the Germans, it is known as dinkel.

I found out that spelt had been grown for some 4,000 years in the area that we live in, since the Bronze and Iron Ages. Carbonized grains of spelt had been found in food remains in the Glastonbury Lake Village excavations. Researching Sharpham Parks history, I learnt that it had a rich and varied farming background, stretching back centuries. The land is first mentioned in ad 978 when King Edwig of Wessex gave it to the thegn Aetholwold. It then passed in and out of the hands of the abbots of Glastonbury for the next 500 years. By 1300 it had been enclosed as a deer park by the abbots, land that would have provided every kind of food for the monks table, with tenant farmers growing a variety of different crops, which would, without doubt, have included spelt.

The business part of my brain knew that to create a whole new Sharpham Park brand I would need a certain something to be the hero product. Instinctively, I knew I had found it. You might ask, why would someone whose background was in fashion design and marketing even contemplate farming? Well, as a small boy I would stay on my grandparents Suffolk farm during the long summer holidays, and whether I was helping to feed the pigs or riding the combine harvester, I was always in seventh heaven. To have a farm of my own was both thrilling and terrifying in equal measure. But also, in a strange way, it felt like coming home.

Our first steps in organic farming were both educational and an eye-opener. We were told by our Soil Association adviser that it would be wise to convert half our landholding to organic status first, so we could get used to the process. The first lesson was salutary. We watched as our lovely team sprayed the conventional wheat crops with fertilizer, pesticides, weedkillers and even growth inhibitors so that the wheat would grow to exactly 39cm/15in for the ease of the combine harvester. These fields looked impressive. Our organic spelt, by contrast, looked a bedraggled mess, full of weeds, nettles and flowers. I started to think, what have I done? But then the spelt began to grow through, and went on growing until it was 1.5m/5ft tall. Since then, weve never looked back.

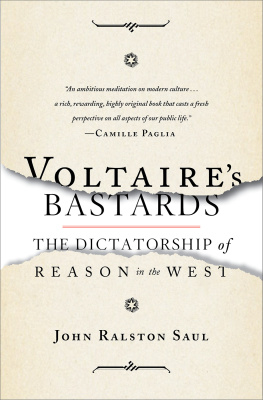

Above: Painting of Sharpham Park and Glastonbury Tor, Rev. W.W. Wheatley, 1843

That year of farming both conventionally and organically was the best thing we ever did. It helped us to understand that the efficient bug-killing regimes that have their place in mass food production (but are banned in organic growing) can and do destroy the insect lifecycle so vital not only to natural bug control but also to the birds and wildlife dependent on them for food. These sprays break down natural immune systems and have done untold damage in destroying the micro-organisms in our soils. We felt that it was time to change all that, and we embarked upon a cycle of organic crop rotation, a system that is used to restore the essential nitrogen, potassium and other minerals in the soil so that crop yields are kept naturally high.

In our first spelt trial, we grew three different types, and found that a hardy old German variety was the best for our soil type and climate. Dehusking the grain presented a real challenge, as one of spelts natural features is its extra-strong outer husk. Luckily, we found a wonderful local watermill, and the owners kindly agreed to have a set of millstones put back into production, especially for our organic spelt.

Finally, when we had our first flour all bagged up, we told the story to Tamasin Day-Lewis, food writer for the Daily Telegraph. She wrote our very first press story about the rebirth of spelt. We were inundated with readers enquiries. Each person had their own tale to tell, often of sensitivity to ordinary wheat, and were desperate to know where they could buy our spelt.

We went on to build our own mill, the only one in the world milling solely stone-ground organic spelt, which was kindly opened by Sophie, Countess of Wessex, in June 2007.

SO WHAT IS SPELT?

Spelt is a member of the grain family, but it has certain properties that make it quite different from wheat, barley, oats or rye. It is a hybrid of emmer wheat and goat grass, and has a distinctive, nutty flavour. There is plenty of evidence that spelt was cultivated by early civilizations, such as in Mesopotamia in the Middle East, around 9,000 years ago. In Britain it is first known to have existed as a main crop in 2000 bce. Later, it came to be known as the Roman armys marching grain. According to legend, warriors in the area now known as Germany ate spelt before going into battle. The Roman legionaries who fought them were so impressed that they added spelt to their diets, too. They would cover vast distances, transporting this vital fuel, sustained by its slow-release energy. Known as farrum, it was used to create a leavened bread that consisted of spelt flour, olive oil, salt, yeast, water and honey.

With the major migrations from Europe to America in the late 1800s, spelt moved with them, and by 1910 more than 600,000 acres of spelt were harvested annually. By the 1970s, however, production in the USA had almost died out with the advent of modern farming techniques and the hybridization of wheat, which meant more efficient harvests. The same trend happened in Europe old-fashioned grains like spelt, which has a husk that protects it from the ravages of both insect and weather, fell out of fashion. The husk is difficult to remove and, once it has been, the yield is 40 per cent lower than wheat. Modern wheat has been bred to lose its husk during harvesting.

Next page