ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This collection of memories would have not been possible without the efforts of numerous individuals and organizations that have collected and safeguarded the images and stories of these Central American immigrants. I am indebted to all my friends who enthusiastically guided me and connected me with others. I am grateful to those, my new friends, who opened their homes to me, trusted me with their cherished memories, and dedicated time to this project.

I would like to thank the following people for sharing their stories and for their insight and guidance: Roberto Alfaro, Pedro Arias, Isabel Cardenas, Francisco Carias Mndez, Omar Corletto, Juan Carlos Cristales, Rony Figueroa, Mario Gee Lopez, Alfredo Gonzalez y Aguilar, Victor Grimaldo, Jose E. Gutierrez, Sandra Gutierrez, Sergio Lewis, Fred Lugo, Elio Martinez, Andres Montoya, Guillermo Palencia, Roland Palencia, Salvador Sanabria, Carmen Suazo, Teresa Tejada, Silvano Torres, Leoncio, Velasquez, Nestor Villatoro, and to all of those who shared their photographs to make this book possible.

I would also like to thank the first people that I sought for support, who embraced this idea, including Stephen Mulherin and Ester E. Hernandez, and especially those who were willing to support me during the initial plans of this book, including Marvin Andrade, Gilda L. Ochoa, Nicolas Orellana, and Horacio N. Roque Ramirez.

I am grateful to Jerry Roberts for believing in this project and for his desire to publish this book and to Arcadia Publishing for providing the opportunity to publish the story of Central Americans.

My appreciation goes to Wayne Goto and Tad Keyes for their expertise in digitizing the images used in this book, photographers Joaquin Romero and Remberto Diaz for their enthusiasm and support, artists Ricardo OMeany and Pehdro Kruhz for their valuable knowledge and referrals, geographer Angie Saldivar for her maps, and professor Beth Baker-Cristales for taking the time to read this text and for her opinion.

Special appreciation goes to POT, who has always respected my work, encouraged me, and given me uplifting words. I am also especially grateful to my friend Rochelle MacAdam, who helped me proofread and gave me her motherly support; I could have not done it without you.

My final gratitude and love goes to Fernando for his support and caring; and lastly to Dinorah for being there when I needed her.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, James Paul, and Eugene Turner. Changing Faces, Changing Places: Mapping Southern Californians . Northridge, CA: California State University, 2002.

Avalos, Hector. Introduction to the U.S. Latina and Latino Religious Experience . Boston, MA: Brill Academic Publishers, 2004.

Chinchilla, Norma Stoltz, and Nora Hamilton. Seeking Community in Global City: Guatemalans & Salvadorans in Los Angeles . Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2001.

Moore, Joan and Raquel Pinderhughes. In the Barrios, Latinos and the Underclass Debate . New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1993.

Ochoa, Enrique, and Gilda Ochoa. Latino Los Angeles Transformations, Communities, and Activism . Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2005.

Waldinger, Roger, and Mehdi Bozorgmehr. Ethnic Los Angeles . New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1996.

Weaver, Frederick Stirton. Inside the Volcano, the History and Political Economy of Central America . San Francisco: Westview Press, 1994.

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

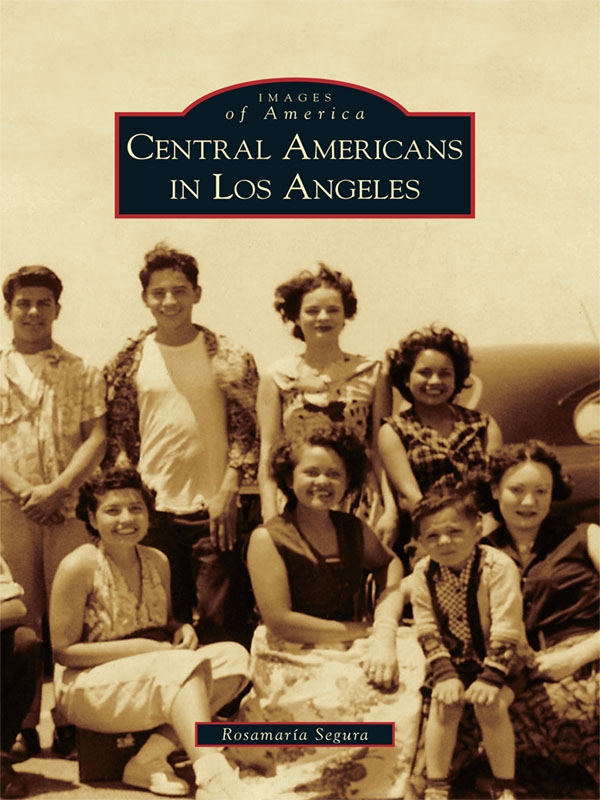

CENTRAL AMERICAN IN LOS ANGELES

As early as the 1930s, Central Americans belonging to coffee growers elite families traveled to California for vacations and business trips. When the global depression of the 1930s hit the coffee market, it affected the regional economies of these countries. Later, small numbers of upper class and middle-class people immigrated to San Francisco and Los Angeles. By the 1940s and 1950s, another small group of Central Americans came to Los Angeles. This time it was the immigrants from the working class; a number of them came with work permits to fill vacant jobs in a variety of industries. Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, additional immigrants traveled to Los Angeles. Some came to study or to visit relatives and later returned to their native countries, and others stayed and integrated into the working and social life of Los Angeles. After the late 1970s, most Central American migration was related to the civil wars in some countries and the resulting economic devastation.

In general, when Central Americans came, many of them ended up living in the Westlake and MacArthur Park neighborhoods, better known as Pico-Union. These neighborhoods are located in the urban core of Los Angeles south of the Hollywood Freeway and north of the Santa Monica Freeway but west of the Harbor Freeway and east of Hoover Street. The area is surrounded by Silverlake and Echo Park to the north, the West-Adams district to the south, Koreatown to the west, and the downtown district to the east. The neighborhood was at its greatest development in the 1930s; it had a predominately white population, and it was a bedroom community for those who worked downtown. With the proliferation of the automobile, whites began to move west to newly developed suburbs. At the same time, Mexicans and Mexican Americans, who were displaced from agricultural land that had been taken for new suburban development, moved to the Pico-Union area. Since then, it has become a transient neighborhood for recent Latino immigrants, starting with many Mexicans who later moved to other areas, such as the already well-established Boyle Heights and East Los Angeles. For the newly arrived Central Americans, the neighborhoods around Pico-Union have always been attractive because of the abundant multifamily residential buildings and the already established Latino community.

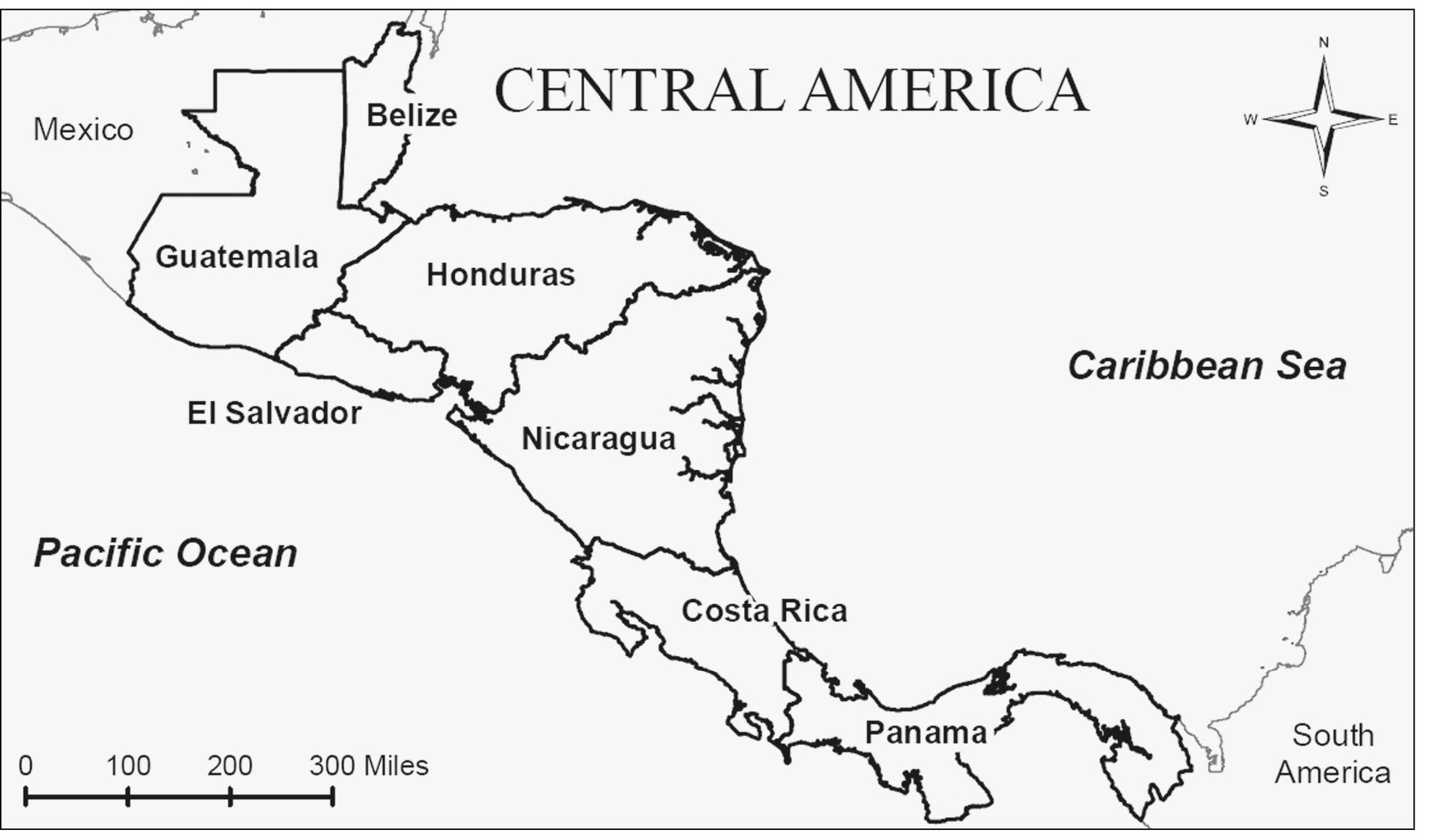

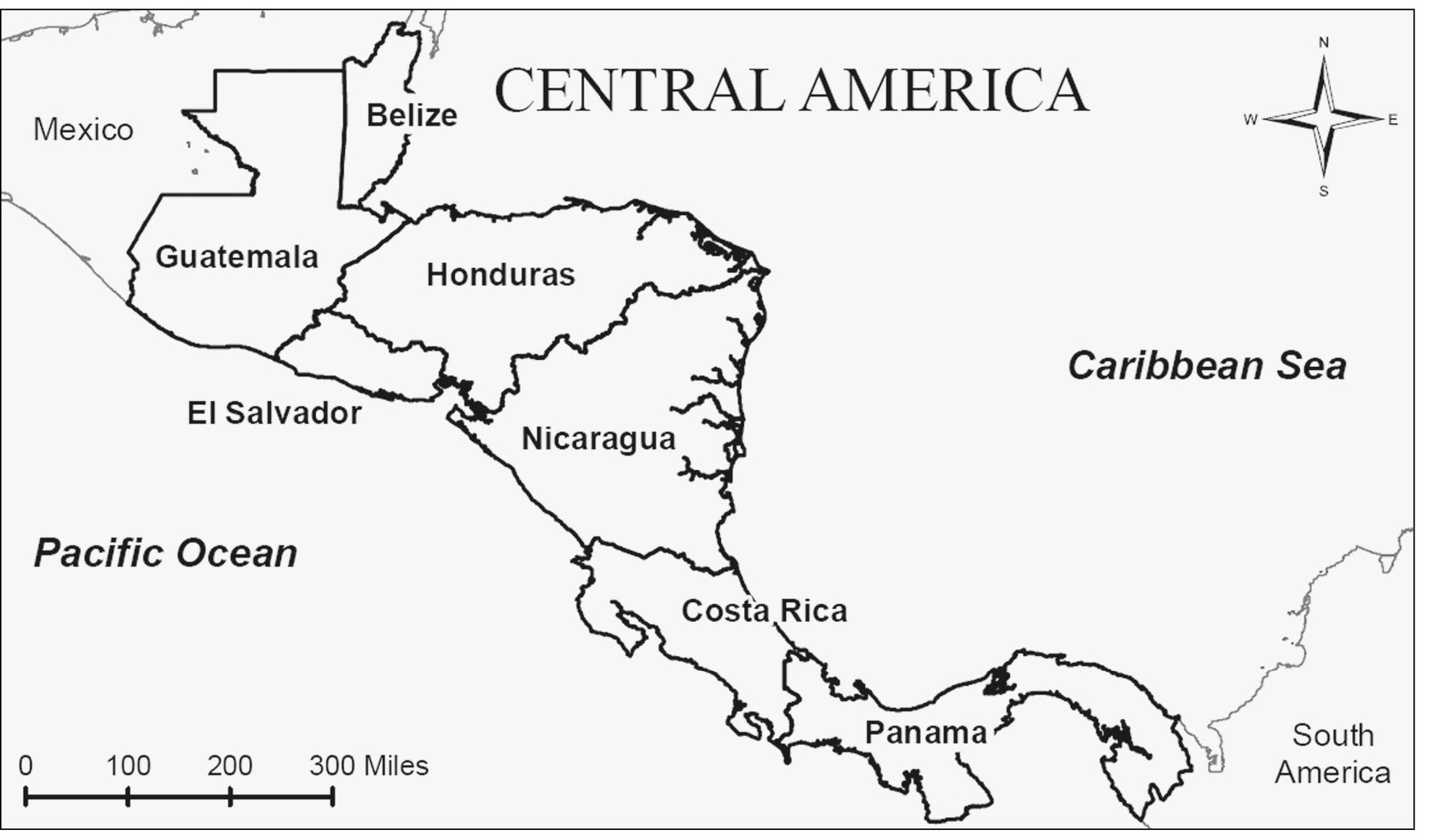

The Central American region is of relatively small size in contrast to the rest of the continent; however, its geographic location plays a significant role because it is like a bridge linking North and South America and therefore its peoples. The total area of Central America is 523,780 square kilometers, as compared to the United States, which has approximately 9,826,675 square kilometers. The region, in spite of its small size, has numerous political, economic, and cultural complexities. The pre-Columbian period coincided with Mesoamerican civilization, which occupied much of the northwestern areas from Guatemala through Honduras, Belize, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. Mesoamerican and Andean cultures met somewhere between Costa Rica and Panama; however, this unity was mostly cultural rather than political. The postChristopher Columbus discovery period was dominated by Spains influence for nearly 300 centuries until each of these countries won independence from Spain in 1821, with the exception of Belize, which was part of the British Empire and did not become independent until 1981. After the Central American region gained its independence, there were several attempts to unite the region as whole country; however, to this day, each country remains separate, independent entities. (Courtesy of Angie Saldivar.)