INTRODUCTION

My familys farmhouse sits on a hill right below the medieval town of Gradara, a quaint bouquet of houses famous for its top-quality restaurants, its romantic candlelit alleys, and the massive, elegant Gradara Castlea storied landmark that was destroyed and rebuilt after a war between two families in the 1500s.

I spent my childhood immersed in this fairy talelike scenery. We have lived on a quiet road on the outskirts of Gradara for generations. Our house, a large ocher building with wooden blinds, is surrounded by fruit and olive yards, almond and walnut trees, and a large field that once hosted a vineyard, which died along with my great-grandfather. From our farmhouse, you can see the Adriatic Sea stretch far at each end of the scenery, from the southern hilly coast of Le Marche, carpeted in woods and green fields, to the flat Emilia-Romagna region in Northeastern Italy.

Gradara is right on the border between these two distinct regionseach with its own dialect, history, and cuisine. A few miles to the west, Emilia-Romagna is famous for its iconic dishes and ingredients. Much of what people think of as Italian food comes from here: Parmigiano-Reggiano, Bolognese sauce, prosciutto di Parma. Italians agree, as much as we can agree on anything related to food, that Emilia-Romagnas cuisine is one of the greatest in all of Italy. South of our farm is the Marche region, an unspoiled, rural region between the Apennine Mountains and the Adriatic coast. Le Marche is filled with medieval villages and the land is hilly, gradually sloping toward the sea. Its cuisine is lesser-known than Emilia-Romagnas but just as delicious, bristling with the flavors left behind by thousands of years of invasions.

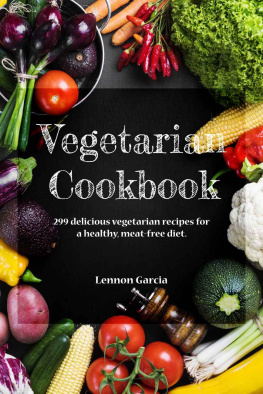

Meat features strongly in the cuisine of both areas. A typical meal starts with salami and a selection of cured meats, followed by pasta served with sausage or filled with a mixture of ground beef, pork, and charcuterie. Sauces are made with chicken giblets or browned chicken liver. Pork and chicken are prevalent in the mountains, and seafood dominates on the coast.

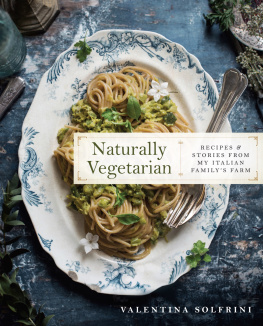

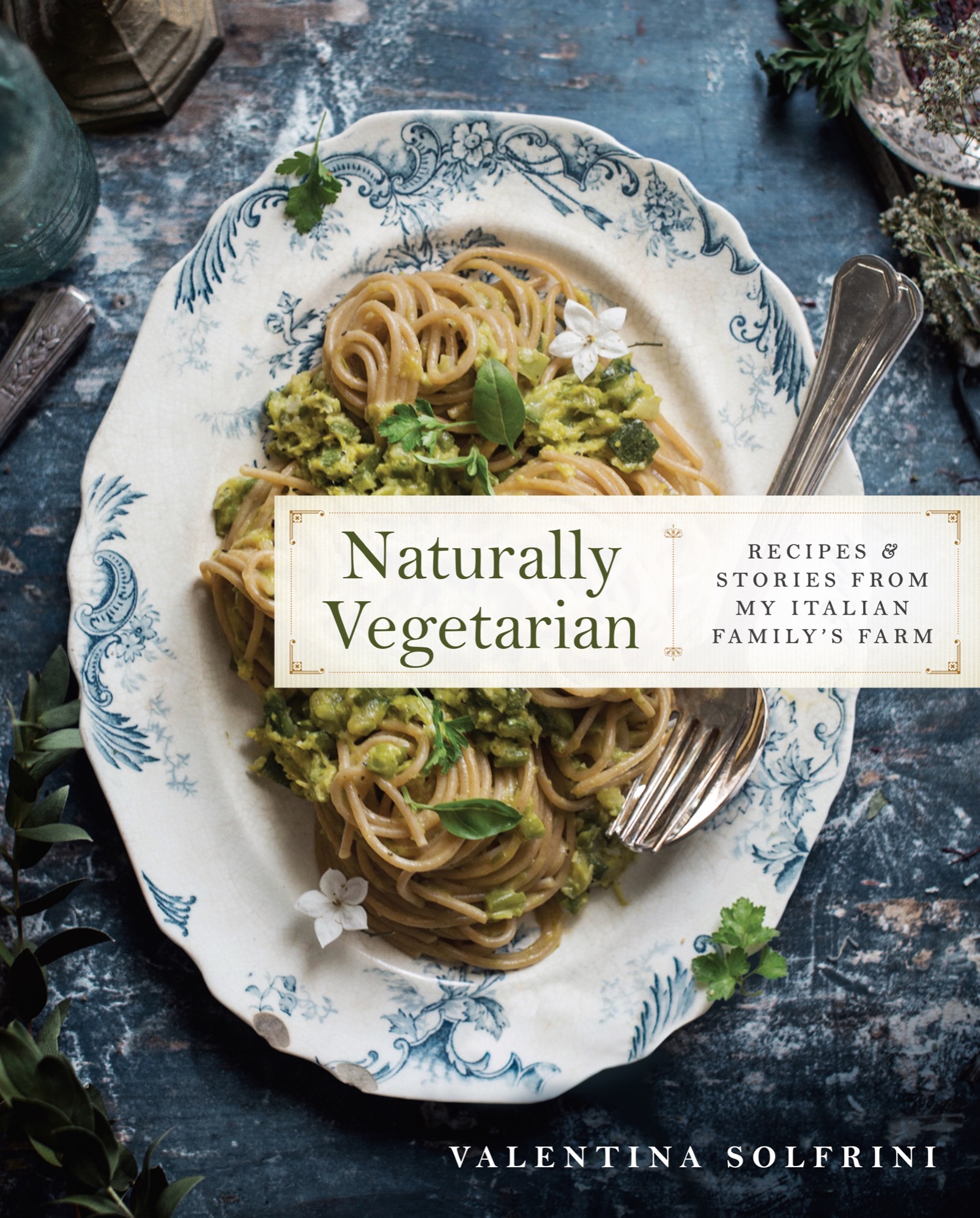

Yet its from the intersection of these regions that I cook and write about plant-based food. In a back room of our farmhouse, in an unused space filled with old furniture and beautiful light, I photograph and write my blog, Hortus Cuisine.

How did I become a standard-bearer for vegetarian Italian cuisine? Quite by accident. I am not a trained chef, and still today I do enjoy the occasional local seafood and traditional cheeses, which makes me more of a supporter of a mostly plant-based way of eating rather than a full vegetarian.

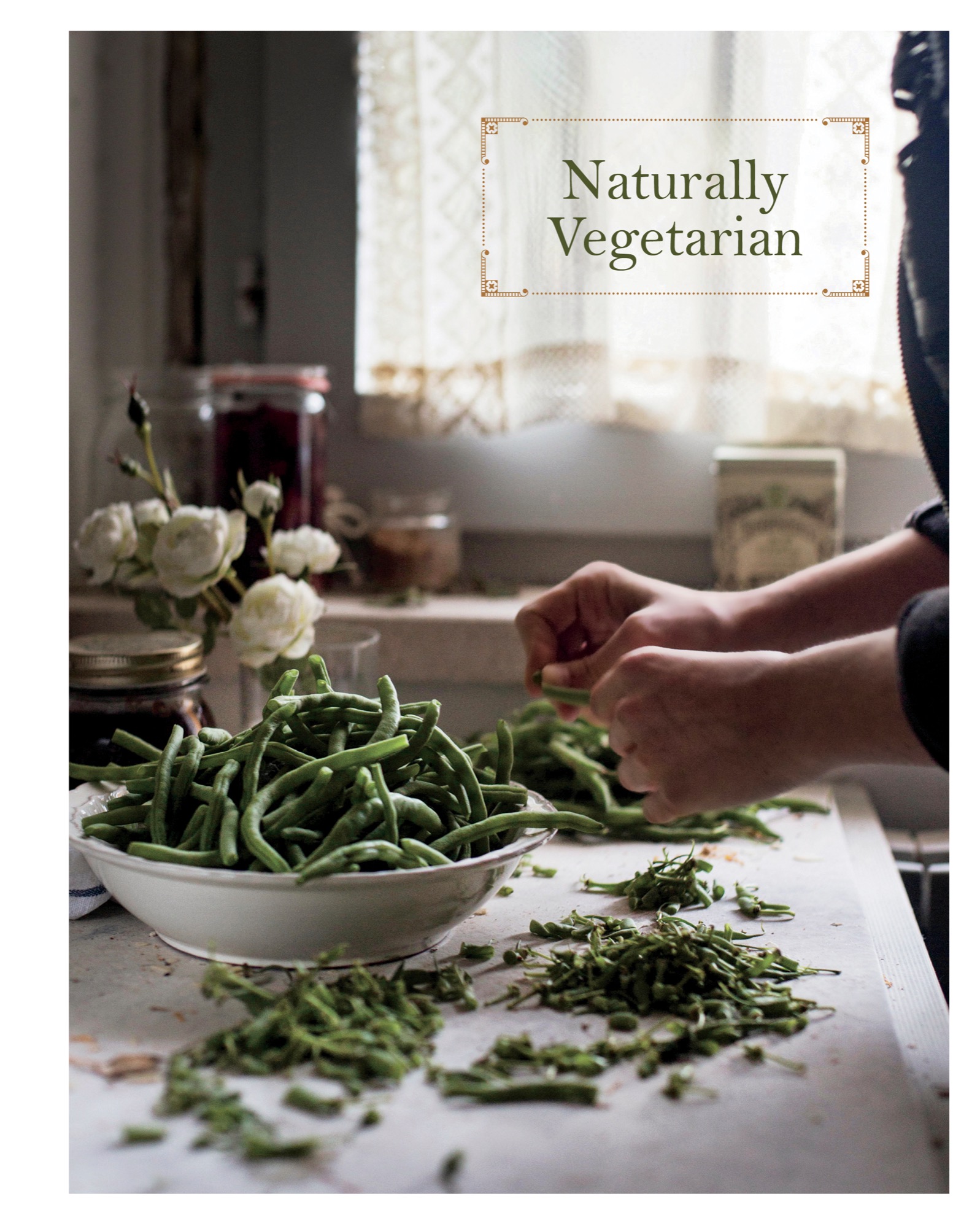

As the daughter of a farming family, I grew up eating the seasonal, fresh food prepared by my mother and grandmother, who were both professional cooks. My life was filled with homemade food and cooking, and it was not often that we set foot in a restaurant. My grandmother and my mother alike didnt really trust other people to prepare their food.

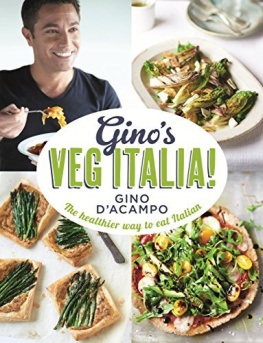

My grandma worked as a pasta maker at Bolognas fairs, and she could roll a sheet of dough out thin like no one else. Shed say that if you make pasta in Bologna, it has to be thin enough that you can see St. Peters Cathedral through it. Likewise, my mom has worked as a cook in restaurants and hotels all her life. She started out at eleven in a pastry shop where she could not even reach the counter and had to stand on a little stool. With two women like that in the house, it was no wonder I would learn a thing or two about cooking! It was such a basic and everyday part of life.

But it was all something I took for granted. My passion wasnt food but art. For years, I studied design and illustration. My teachers said I had promise and encouraged me. When I graduated, I wanted to experience the vibe of a big city, to discover new things for my art and my future. So I packed my bags, said good-bye to my family, and moved to New York. What city could possibly be better?

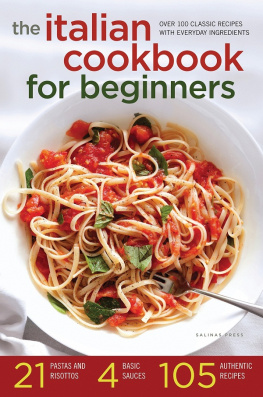

I loved the chaos, the people, and even the smells. And I was amused by the American idea of Italian cooking: Garlic powdera flavor I had never really experienced, was liberally used in every tomato sauce I came across. I found cheeses everywhere in supermarkets labeled as Italian that did not taste one bit Italian, and everyone thought Alfredo sauce was actually a real thing, when in Italy it is not. I remember how I told an American food-lover I met that I thought garlic powder was a distinctly American flavor. He said, Thats funny. People here think garlic powder is a distinctly Italian flavor! I face-palmed myself. It was a seemingly endless, yet incredibly fun, learning process and window into the way other cultures try to translate a cuisine.

One of the things that struck me the most about the city was that cooking was largely seen as a task rather than a pleasure. It surprised me how little the average New Yorker cooked at home. But in this new place with all new influences, I finally had a chance to test my own cooking. I experimented in my tiny kitchen in a 270-square-foot apartment in Yorkville for a few hours most evenings after a long day of work. I visited every hidden and known food shop I could possibly find in both Brooklyn and the city, and walked up and down the seemingly endless cookbook aisles in bookstores. I found some authentic preparations of Italian dishesgnocchi and ravioli, doused in truffle and cheese sauce or fried in butter and sageand I learned that Italian wines, pecorino cheeses, and