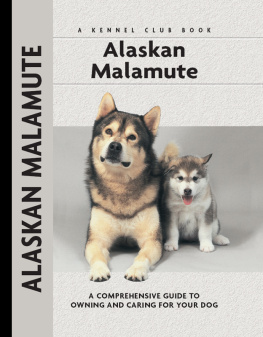

The Alaskan Malamute is one of the oldest and most admired Arctic sled dogs. These powerful working dogs are native to the northern regions of North America and were first bred by a tribe of Inuits in the late 1800s. The dogs were primarily used to haul heavy sleds across long distances in extremely harsh winter weather. The breed gets its name from a distinguished group of Eskimos that were known as the Mahlamuits or Mahlemuts. This native Inuit tribe was believed to have first settled along the shorelines of the Kotzebue Sound, located in the upper western section of Alaska. The Eskimo people of this region greatly depended on the dogs for survival. The dogs were used to haul food, supplies and other necessary provisions.

The development of the sled that was headed by a working team of Alaskan Malamutes was essential for moving meat from the original hunt location back to the Inuit home base. The unfavorable weather conditions of the Arctic often forced the Inuit people to travel great distances to find the food and supplies essential for their survival. During this time, the Arctic was one of the most difficult areas in which to reside. The subfreezing temperatures, unrelenting snow and lack of resources in the area made the Alaskan Malamute extremely valuable. The breeds strength, endurance, obedient nature and sled-dog qualities made it a vital component of the Eskimo peoples survival.

Besides their ability to transport heavy loads of freight across long trails of snow and ice, Alaskan Malamutes were also valued for their superb hunting ability. It was not uncommon for them to hunt polar bears, moose, wolves, walruses and any other large, fierce predators that attempted to interfere with their long journeys or were needed for food. The combination of the breeds wolf-like appearance and its ability to work as a team in the killing of large predators is the likely origin of its wolf-dog nickname. Even more probable, the name wolf-dog was common because some believed the breed had been crossed with wolves. Some reports even indicate that Alaskan Malamutes assisted the Inuit Eskimos by locating blow-holes where air-seeking seals were situated.

PART OF THE PACK

The Alaskan Malamutes admiration of and fondness for family companionship and the breeds love of children were apparent from the very beginning. During extremely cold nights, the dogs were often used as an excellent means of warmth and comfort. It wasnt uncommon to see a pack of Alaskan Malamutes snuggling and sleeping with small Eskimo children.

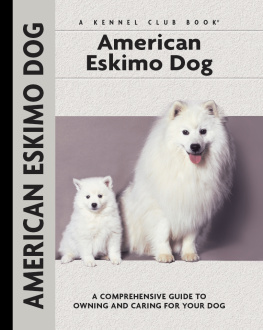

Other Arctic breeds included the pure-white Samoyed, also revered for its people-loving temperament. This abundantly coated breed is also a popular pet due to its outgoing, happy nature.

Many dog historians are confident that the Alaskan Malamute is related to some of the other Arctic breeds, such as the Siberian Husky, Samoyed and other similar Eskimo dogs of Greenland and Labrador. Like these relatives, the Malamute was valued for its ability to survive under harsh weather conditions and on minimal amounts of food.

Early specimens of the breed varied in type and conformation depending on conditions to which they were exposed. The type of terrain, amounts of snow and how the dogs were used and treated profoundly affected how they looked and performed. The dogs coats differed in length and texture, and the length of head, muzzle, legs and other distinctive features also varied from dog to dog.

P HOTO BY K ENT AND D ONNA D ANNEN.

Dog sledding is a popular sport derived from the Eskimos practice of using dogs for over-the-snow transportation of people and goods.

THE POPULARITY OF DOG SLEDDING AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE BREED

Dog sledding has been very popular for quite some time. The Alaskan Gold Rush of the late 1800s and early 1900s attracted working teams from all of Alaska and the Yukon. Although there were other Arctic breeds represented in the working sled-dog groups, the Alaskan Malamute was quickly recognized for its many fine characteristics. The breeds thick coat, durability, intelligence and ability to work soundly under adverse conditions made it far superior to its Arctic canine relatives as team leaders. During this time, people flocked from all over the United States to the Alaskan region in search of gold, which was first discovered in 1896 in Bonanza Creek in the Klondike. The demand for the breed became overwhelming and the stock was quickly exhausted.

When the mushers (sled-dog drivers) of the gold rush era werent out looking for riches, they participated in sled-dog racing as their favorite pastime. Sled-dog racing quickly became the premier sport, and gambling on these events was very popular in the local bars. So popular, in fact, that in 1908 the Nome Kennel Club was formed, and this organization was responsible for hosting a 408-mile All-Alaska sled dog race. Individuals from all over Alaska and the vicinity gathered together their sleds and the swiftest dogs they could find to take part in the sweepstakes. The winners of these events obtained tremendous recognition and prize money and became instant celebrities both within and outside the region.

IDITAROD

The Iditarod, also called the Last Great Race, is run each year in February from Anchorage to Nome. The dogs travel a distance of over 1,000 miles.

Very much like todays recognized sports heroes and celebrities, the sled-dog stars of this period became well-known in both the United States and Alaska (before its statehood). Scotty Allen, John Johnson and Leonhard Seppala were just a few of the finest sled-dog drivers and trainers of this time. Scotty Allen was particularly important to the sport. He was instrumental in organizing the first official sled-dog race, which was the All-Alaska Sweepstakes.

EXPANSION AND BREED RECOGNITION

The Byrd Expedition, headed by Richard E. Byrd, was one of the greatest geological sled-dog expeditions of the early 1900s. Byrd was a naval aviation officer and was interested in becoming the first person to fly over the South Pole. During his expedition, he would need a group of sled-dog teams to transfer equipment across nine miles of icy terrain. Arthur Walden was the head dog-driver of Byrds team, and many top dogs from different locations were gathered for the event. The dogs carried food, coal and other important supplies for geologists and other expedition participants. Byrds complete trip totaled 1,600 miles, and he returned home to a warm welcome. This geological expedition would go on to help the breeds recognition even further, and was the first of many expeditions to follow.

TOOTH TACTICS

The teeth of the Alaskan Malamute were often pulled entirely or filed down. Frequently the dogs would chew through their harnesses in an attempt to set themselves free. The filing or removing of teeth not only prevented them from chewing but also lessened the chance of injury if a fight were to break out among the pack.

Some years later, Admiral Richard Byrd would conduct a second Antarctic expedition. Once again Byrd would fund most of the trip himself; its purpose was similar to the first voyage, focusing on scientific research and the study of Antarctic weather patterns. Captain Michael Innes-Taylor was designated chief dog-driver for this event.

Next page