CONTENTS

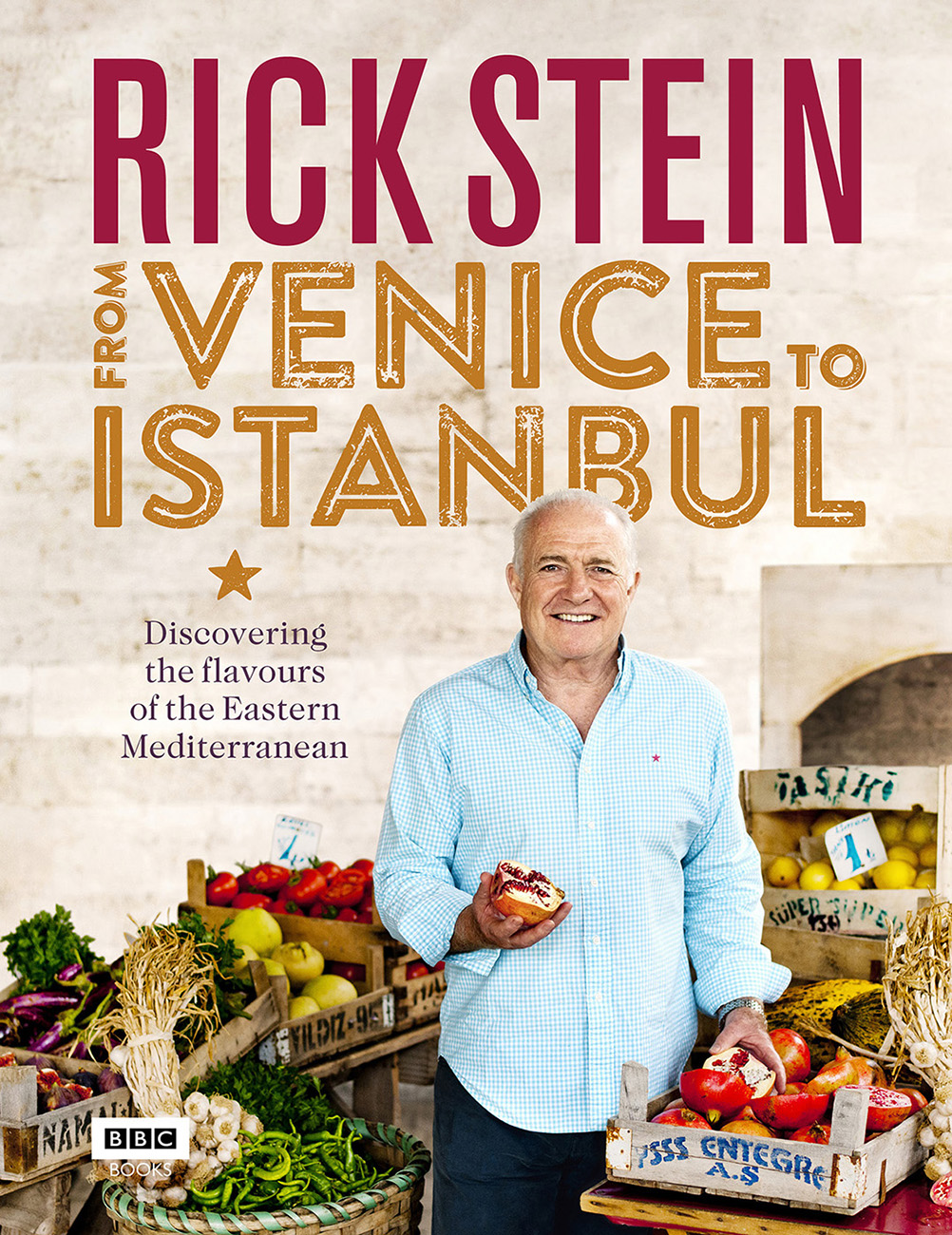

ABOUT THE BOOK

This is a memorable food odyssey: journeying through an ancient landscape discovering great food, and creating dishes from recipes that have lasted the course of time.

From the mythical heart of Greece to the fruits of the Black Sea coast, from lesser-known Venetian and Croatian flavours to the spices and aromas of Turkey and beyond the cuisine of the Eastern Mediterranean is a vibrant melting pot brimming with character.

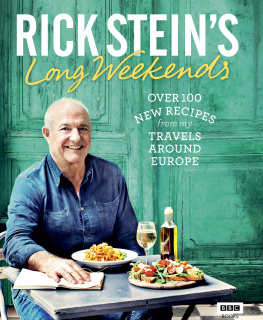

Accompanying the major BBC Two series, Rick Stein: From Venice to Istanbul includes over 100 spectacular recipes discovered by Rick during his travels in the region: the ultimate mezze spread of baba ghanoush, pide bread and keftedes, mouthwatering garlic shrimps with soft polenta, heavenly Dalmatian fresh fig tart.

Packed with stunning photography of the food and locations, and filled with Ricks passion for fresh produce and authentic cooking, this is an inspiring collection of delicious recipes to evoke the magic of the Eastern Mediterranean at home.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

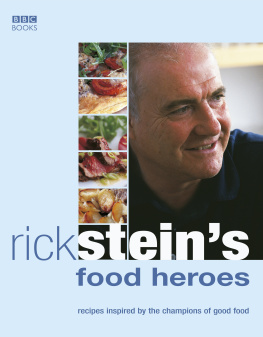

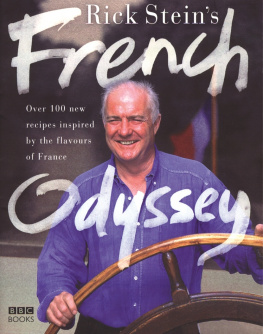

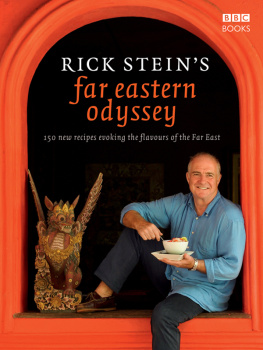

RICK STEINS passion for using good-quality local produce and his talent for creating delicious flavour combinations in his books and restaurants have won him a host of awards, accolades and fans. As well as presenting a number of television series, he has published many bestselling cookery books, including French Odyssey, Coast to Coast, Far Eastern Odyssey, Rick Steins Spain and Rick Steins India.

Rick has always believed in showcasing local seafood and farm produce in his four restaurants in Padstow, Cornwall, where he also has a seafood cookery school, food shops and a pub in the nearby village of St Merryn. In 2003 Rick was awarded an OBE for services to West Country tourism. He divides his time between Padstow and Australia, where he also has a seafood restaurant in Mollymook, NSW.

This book is dedicated to Ed, Jack and Charlie and Sas, Zach and Olive

INTRODUCTION

To fit in with work at the restaurant I write my recipes in the morning. I start at ten thirty and the thought of lunch becomes a growing pleasure as I get hungrier. Its around then that my heart turns fondly to thoughts of the Eastern Mediterranean, the olive oil, the tomatoes, the red onions, the wild oregano, the lemons, the sweet fish, the lean lamb, the wine, the olives, the capers and the garlic. It turns, too, to potatoes so waxy that frying them in wedges in olive oil makes the best chips in the world. I forget the richly spiced dishes of my last journey to India and I think instead of the lightly aromatic quality of a simple fish stew of John Dory and rascasse from Pylos in Greece, made just with onions, garlic, white wine, potatoes and lots of olive oil. I sat down with my friends at the restaurant there, having ordered a Greek salad and some bread, which clearly came from the bakery in the square, and a bottle of white wine that was a blend of Chardonnay and Gewrztraminer. It was lovely. Up to then, I had been ordering retsina, but somehow its scent of pine resin didnt carry the same shock of strangeness as it did in the 1970s. In those days, there was nothing else other than a white called Domestica, which had the same effect on serotonin levels as a British beer called Whitbread Tankard you drank it, but felt there had to be a better way. The Greek salad had changed for the better, too. There was a whole slab of feta on top of the peeled cucumbers, tomatoes, onions and olives, which had been sprinkled with oregano. The olive oil and vinegar came in separate bottles: profligate with the oil and miserly with the vinegar is my take on a dressing, then salt and black pepper, and break up that gorgeous crumbly feta into the salad.

The fish stew was nothing remarkable but the potatoes were warm and earthy, the fish straight out of the bay, the bread still warm, the wine cool, tart and aromatic. That night we went filming in a hillside village called Messochori. Its restaurant, Trixordo, is famous for rebetiko: urban poor peoples music, like the blues, about the harsh realities of living under the radar. Music as the anthropologist Elias Petropoulos said, of the jail and the hash den; songs of meraki, kefi and kaimos love, joy and sorrow like the dance in the film Zorba the Greek. When Zorba dances, you dance it said on the poster of the film when it was released in the 1960s. I read the book, by Nikos Kazantzakis, on a long sunny voyage in a caique to the island of Kalymnos. I remember the continual presence of death in the novel, but also the sun, the serenity, the wine-dark sea, the white houses and, as we sailed, the thrill of blue distant islands, hills of goats and olive groves, limestone rocks and beaches all around and the scent of mountain herbs on the breeze. The book combined the darkness of death with a joy, too, in Zorbas affirmation of life. You might as well dance, it said to me.

That night the spirited rebetiko dancers promised to us by the restaurant owner, our fixer, Mr Karalis, failed to show up. It turned out they had already started the summer season working in the beach bars of Kavos on Corfu. Mr Karalis prepared a lamb and potato stew with olive oil and lemon in the wood-fired oven in the garden. It was plain he didnt do it very often, but his lamb turned out deliciously lemony and salty. At the same time the cook at the restaurant made a pile of pancakes, each one sprinkled with grated mizithra cheese, pungent and salty. Thats going to be tasteless, I thought, but it wasnt. I was almost looking for things not to be good, only to be proved wrong each time.

There was one rebetiko dancer who didnt exactly look as though he possessed a fiery soul like an artist of flamenco, which rebetiko so resembles. The musicians, playing bouzouki, guitar and baglamas, all looked like music teachers, but they entered into the spirit of the thing and the dancer clearly knew the dance. A few English and Germans got up and I joined in. We all started holding hands and swaying, kicking our feet and clicking our fingers, with me thinking about the shared humanity of flamenco, blues or rebetiko, and how a rubbish dancer like me can suddenly dance if the music is that soulful.

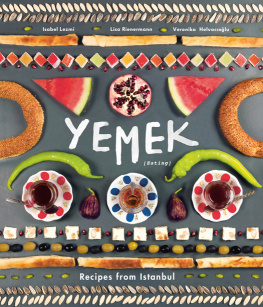

How can we know the dancer from the dance? wrote Yeats. It was thoughts from another Yeats poem, Sailing to Byzantium, that accompanied me on this culinary journey from Venice to Croatia, Albania, Greece and Turkey. Byzantium, as Istanbul was known in ancient times, represented to him the artistic imagination; he thought of it as a place of fabulous colour and brightness. The thought of finishing in Istanbul filled me, too, with a sense of ending in one of the worlds great cities, where the food in its opulent complexity would match the images of golden mosaics, and a fabulous former cathedral, Hagia Sophia, would put The fury and the mire of human veins into perspective.

Even in Venice the shapes and colours of Byzantine art and architecture pointed the way. A lunch at Locanda Cipriani on the island of Torcello in the lagoon necessitated a return to the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, there to gaze at the sublime mosaic of the Virgin and Child, her expression one of mystic piety as she points with her delicate long fingers to the infant Christ as the source of the salvation of mankind. The gold background, the towering figure in blue and the infant with the face of someone much older are like a portal into a different world, one that is echoed to me by the food from this part of the world. So often in Turkey I kept thinking of how the flavours were as if from a parallel universe: the sharpness of yogurt, common in so many dishes, and its affinity with lamb; the lemony favour of sumac; the spiciness of red pepper paste; the plethora of fruit, nuts and cinnamon in rice dishes; the fondness for aniseed-flavoured drinks and smoky aubergines. The acidic and salty cheeses from sheep and goats milk, some matured in goat skins. Salads made from boiled wheat, grains flavoured with pomegranate molasses, pies made with crisp filo pastry filled with the same tart cheese and wild greens gathered from the hillsides. The hot menthol flavour of wild oregano. A flatbread sandwich of cold lambs brains, red onion, tomato, parsley and chilli flakes, sold with a sour drink, algam, of fermented and salted purple carrot juice. I often found myself struggling to take in the many new and strange flavours thrust on me, tastes that would eventually fill my memory with nostalgia.