To the brave women who came with their men into the Appalachian wilderness, who planted the gardens and raised the children, who cooked and laid by and never wasted, and who made one-room cabins into loving homes, the author extends his heartfelt gratitude.

Thank you, Mother, thank you Grandma, and thanks to the many who came before.

Mention Appalachian cuisine to an experienced cook from Flag Pond, Tennessee, or Spruce Pine, North Carolina, and youll likely receive a blank stare in response. Most of the folks who live in the mountainous regions of eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina continue to prepare dishes that have been enjoyed here for generations. Its just home cooking, theyll saynot cuisine.

But if you look closely, youll discover how the influences of southern Appalachias traditions, long isolation, and climate have molded its foodways, distinguishing them from the recipes of the Carolina Low Country, Creole and Cajun foods of Louisiana, and the soul food of the Mississippi Delta. At the same time, Appalachian cooking reflects hints of all of these cuisines. We cook our greens with ham hocks, but theyre more likely to be turnip greens than collards. Black walnuts, rather than the pecans of Georgia, lend flavor and crunch to our desserts. We eat a lot more pinto beans than black-eyed peas. We make corn bread and biscuits to serve with nearly every meal, and we do love barbecue, but we dont do it the same way they do in other places. Cooks from western North Carolina dont make barbecue like their neighbors in the eastern reaches of the state, and East Tennessee barbecue masters have a different approach than their counterparts in Memphis.

In fact, the similarities between the barbecue prepared on either side of the mountains reflects the long, shared history of the mountain people. Its not that other regional cuisines are badfar from it. We just have our own way of doing things here in the mountains, and weve found no reason to change. Once you become familiar with the flavors of this region, you might just understand why thats true.

Where Mountains Are Kings

The Appalachian Mountains were formed in a geologic event that began some 400 million years ago. Running from Maine to Georgia, the mountains reach their loftiest heights in the peaks that lie between North Carolina and Tennessee. The easternmost range, the Blue Ridge, includes the highest peak east of the Mississippi River, Mt. Mitchell at 6,684 feet, and numerous other peaks within the Appalachians that rise above 6,000 feet. Approaching the Blue Ridge from the east you will realize why its abrupt ascent from the Carolina piedmont presented a formidable obstacle to anyone who hoped to traverse it and reach the sprawling American heartland to the west.

The southern Appalachians were never covered by the great ice sheets that crept southward from the Arctic and then retreated about 15,000 years ago. Thus, they served as a refuge for many plants and animals that are now found mostly in northern latitudes. When it comes to spotting varieties of plants and species of animals, traveling from a low valley in the Appalachians to the summit of one of the taller peaks is much like taking a tour up the eastern seaboard to the maritime provinces of Canada.

The mountains have nurtured abundant life throughout their long history. Whole groups of salamanders evolved here, for example, and 100 species of trees are found in the Great Smoky Mountains National Parkabout as many as are found in all of Europe, according to information compiled by the National Park Service. When the earliest hunter-gatherers arrived here millennia ago, they found an abundance of game, fish, fowl, nuts, berries, fruits, roots, herbs, mushrooms, and invertebrates without equal elsewhere in the temperate zone. From the first tender, nutritious shoots of pokeweed to the rich, smoky black walnuts in their rock-hard shells to the sweet, spicy, frost-kissed persimmons, the woods provided a bountiful harvest nine months of the year. About 2,000 years ago, the people known as the Woodland Indians began to cultivate crops, including those brought into the region from elsewhere, such as the corn, sunflowers, and squash plants endemic to Mesoamerica, as well as grapes and other native food plants.

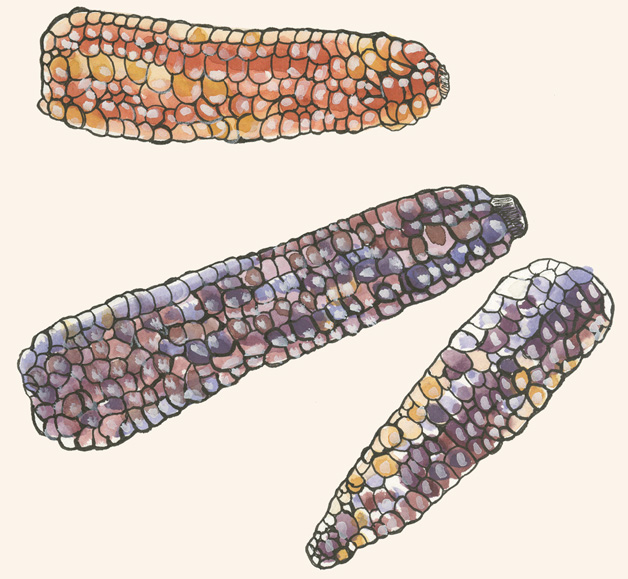

The Tennessee Valley region is the cradle of agriculture in the Southeast. Around 1000 CE, the culture of the Mississippian Native Americans flourished throughout eastern North America. The Mississippians built extensive cities, and their often-beautiful artifacts suggest a thriving economy capable of supporting artisans who created objects with more than purely utilitarian design. During the next 500 years, these people perfected the cultivation of corn.

The Mississippians were the first Tennesseans to recognize the value of the areas broad river bottoms for agriculture. They began to construct villages just outside the floodplain, which permitted clearing of large tracts for corn cultivation. They also learned to cultivate the other two crops of the Three Sisters, squash and beans. Nevertheless, wild foods continued to form a significant part of the Mississippian diet.

The abundance of food led to an increase in population, and gradually, a complex and sophisticated culture emerged. The Mississippian culture was strong in 1500 CE, but with the arrival of Europeans, everything changed.

In the early 1500s, Europeans made isolated forays into the mountains of the South in search of gold. Finding none, they apparently lost interest in the mountains and the people who inhabited them. The earliest recorded European contact with the Mississippian people was in 1540 between the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto and the villagers of Chiaha, about where Dandridge, Tennessee sits today.

Unfortunately, the Spanish brought Old World diseases, including smallpox, that devastated the Mississippians and provoked wars among the various factions that existed within their society. The Cherokee people, who inhabited the Tennessee Valley at the time white settlers began to arrive, were the remnants of a nation driven from its ancestral homeland in the areas now known as Ohio and West Virginia after a long series of wars with the Delaware tribe. The Cherokee had barely established towns along the major rivers of the region when the Europeans began moving in. On the North Carolina side of the mountains, the Catawba tribe continued to dominate, but they too were slowly pushed aside by the relentless onslaught of new arrivals from teeming colonies along the Atlantic coast.

It was not until the 1730s that settlement in the overmountain region began in earnest. Colonists began to arrive in western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee from Virginia, and others came north from the Carolina Low Country. The isolation and hardships imposed by the topography there shaped, through both direct and indirect means, the mountain culture and traditions. The mild climate, fertile soils, and plentiful rainfall of the area, combined with its abundance of wild game and fish, influenced the cooking of the region in ways that remain to this day.

Early European settlers in the region included the Dutch, English, and Germans, as well as many (although by no means the majority, as is sometimes claimed) Scotch-Irish people. Between 1710 and 1775, some 200,000 settlers emigrated from Ulster to the American colonies. They were mostly Presbyterians who were seeking freedom from attempts by the British Crown to force them to join the Church of England. The majority arrived in Pennsylvania, and from there they migrated to Virginia and ultimately North Carolina and Tennessee; at the time, the latter was known only as North Carolinas western frontier.