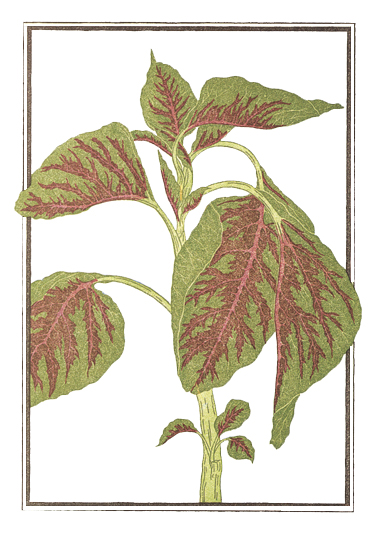

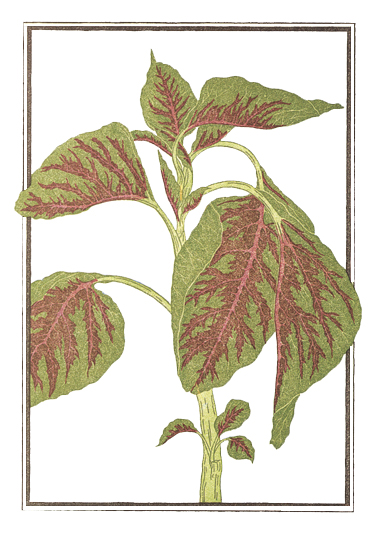

Season: Spring through fall

Amaranth is a new vegetable to many of us, although it has been eaten for centuries just about everywhere in the world. There are a great many species of amaranth, all of them annual and mostly tropical plants that are related to a common weed known as pigweed. The cultivated varieties are grown mostly for their edible greens, which have a distinctive, appealing flavor somewhat like spinach. The weed amaranths are very common, sprouting up in the cracks of sidewalks and in vacant lots, and taste much like their domesticated cousins; there are also amaranths grown for grain and ornamental amaranths with strikingly beautiful flowers.

The leafy amaranths come in an enormous range of sizes, colors, and shapes. Most cultivated varieties belong to the species Amaranthus gangeticus. Leaves can be almost round or lance-shaped, from two to six inches long. Green-leaved varieties are sometimes called tampala, their name in India. There are also red-leaved varieties (the kind favored in China), variegated varieties (one called Josephs Coat has leaves streaked with yellow, red, green, and brown), and very pale green varieties. Older, larger leaves tend to have a stronger flavor than small ones.

We have never cooked with amaranth grain at Chez Panisse, but we use the greens in much the same ways as other salad and cooking greens and have been pleased with the results. We make salads of small red amaranth leaves to accompany seared tuna and salmon tartare, and cook the larger leaves both alone and combined with other greens to serve in pasta dishes.

Unless the leaves are of the tiny beet-colored variety just picked from the garden, amaranth is better cooked. Use the stems as well as the leaves, although thicker stems may need peeling and you may not want to bother. The big, splashy leaves and stems of late-season amaranth sometimes need a preliminary parboiling. Spring and early summer amaranth needs no more than the routine washing and grooming before you get on with the cooking. You will notice that amaranth does not cook down as much as spinach.

Local farmers markets in our part of the country often have amaranth greens for sale. The best are the ones that look the freshest and healthiest. Amaranth greens wilt quickly, so eat them as soon as possible.

The amaranths are easy to grow; seed catalogs often have a wide selection of varieties. They make a speedy and attractive addition to your kitchen garden. The Rodale Press, publishers of Organic Gardening, has made something of a crusade on behalf of the native American grain amaranths, one of the very few grains that are feasible for home growing. Curious gardeners are encouraged to investigate.

Amaranth is such an interesting green that a favorite approach is to cook it quickly, although its robust flavor and texture stand up to long cooking as well. You can proceed along two lines. Sizzle a few slivers of garlic in olive oil, follow with a healthy pinch of salt, and then add the greens. Cover for a minute to let the greens wilt down, then keep tossing until the leaves and stems are tender and no longer taste raw. A second, pan-Asian treatment is to use peanut or corn oil, into which you toss finely sliced or shredded ginger, either alone or with a few slivers of garlic; a dry red chili or two; and then the salt and greens, proceeding as before.

Season: Spring and early fall

Artichokes are the edible, immature flowers of a cultivated thistle that was introduced to America by Italian immigrants who settled near Half Moon Bay in California around the turn of the century. Italians have been practicing artichoke cultivation for at least two thousand years, and to this day they have a more highly developed expertise in its use than most Americans. For example, in Venice, in the spring, it is routine for fresh artichokes to be sold in the market already pared down to their hearts, or bottomslarge globe artichokes expertly turned by hand, as on a lathe, all the leaves cut off, leaving just the thick disk of the flower base and the immature fuzzy flowerets which form what is known as the choke. Experienced market folk turn out these hearts in seconds flat; the leaves get discarded, and the raw white artichoke bottoms are tossed in buckets of water acidulated with lemon juice.

There are artichokes shaped like truncated cones; artichokes that are almost perfectly round; and artichokes with nasty thorns. There are green artichokes, green and violet artichokes, and purple artichokes. They are prepared at Chez Panisse in a great many ways, both raw and cooked, depending on their size and relative maturity. Larger ones are steamed whole and served with aoli (with the leaf tips snipped off if they are very thorny); quartered, stewed, and served in salads; or cut into wedges, browned with tiny new potatoes and small, round spring onions, and finished with a persillade. Artichoke hearts are sliced very thin and baked in a gratin with thyme, cream, and Parmesan. Artichokes are trimmed and stuffed la Provenalwith bread crumbs, parsley, garlic, and anchoviesor with onion, sausage, and mushrooms.

Especially delicious are the tender young buds of artichokes picked before their prickly chokes have developed: simmered at a low temperature in olive oil until soft, then fried at a higher heat so that the leaves open out, flowerlike, and sprinkled with persillade and lemon juice; cooked rapidly in olive oil with white wine, a few thyme sprigs, and garlic slivers until quite soft, a few drops of lemon juice and Parmesan shaved over; or sliced very, very thin and tossed, raw, with olive oil, shavings of Parmesan, and shavings of white truffle. Young artichokes can also be simmered in oil and spices, including a little hot pepper, and preserved in the same oil for an antipasto. Risotti with young artichokes, accompanied by young peas or fava beans, whole or pured, with Parmesan grated over, breathe springtime. So does a ragout made with the same ingredients.

Artichokes produce two crops a year. After the first harvest in the spring, a second crop is ready in the early fall. The artichokes quality varies dramatically over its life cycle. Immature flower heads are crisp and dense, but late in the season they become chokey, and start to open, a sign of overripeness. An artichoke should be harvested and eaten only in the bloom of its youth, never in its maturity. Therefore look for artichokes in the market that are unblemished, tightly closed, entirely unopened, and vibrant in color whether lime-green or bright green and purple. Look at the stem end. The scar should tell you something about how recently it was cut. Buy artichokes as fresh as you can, and dont keep them long before cooking them. Experiment with unusual varieties if you see them in your market; different varieties have distinctly different flavors.

To prepare large artichoke hearts, tear off any small leaves attached to the stem or base, and cut crosswise through the leaves where they begin to taper in toward the top, about an inch and a half above the base; younger artichokes can be cut higher up to preserve more of the tender leaves in the center. Put the artichoke cut side down and carefully trim the leaves (actually scales or bracts) away, leaving just their pale green centers. Pare away the deep green part of the head and stem. You will have only the heart left, with a length of stem still attached. Cut off all but an inch or so of the stem. With a soup spoon or a teaspoon scrape and scoop out the choke from the heart. Fresh artichokes are crisp enough so that this is an easy and simple task, and with a little practice can be done in one motion. Have ready a bowl of acidulated water into which you can immediately drop the artichokes as they are trimmed, to reduce browning from oxidation. Or lightly rub the artichoke hearts with some olive oil. The hearts are now ready for however they are to be cookedsliced, sauted, boiled, stuffed and braised, and so on.