Table of Contents

TRANSITIONS: ASIA AND ASIAN AMERICA

Series Editor, Mark Selden

Our Land Was a Forest. An Ainu Memoir, Kayano Shigeru

The Political Economy of Chinas Financial Reforms: Finance in Late Development, Paul Bowles and Gordon White

Reinventing Vietnamese Socialism: Doi Moi in Comparative Perspective, edited by William S. Turley and Mark Selden

FORTHCOMING

Privatizing Malaysia: Rents, Rhetoric, Realities, edited by Jomo Kwame Sundaram

The Politics of Democratization: Vicissitudes and Universals in the East Asian Experience, edited by Edward Friedman

City States in the Global Economy: Industrial Restructuring in Hong Kong and Singapore, Tai-lok Lui, Stephen Chiu, and Kong-chong Ho

The Origins of the Great Leap Forward, Jean-Luc Domenach

Japanese Labor and Labor Movements, Kumazawa Makoto

Unofficial Histories: Chinese Reportage from the Era of Reform, edited by Thomas Moran

The Middle Peasant and Social Change: The Communist Movement in the Taihang Base Area, 1937-1945, David Goodman

Twentieth-Century China: An Interpretive History, Peter Zarrow

Moving Mountains: Women and Feminism in Contemporary Japan, Kanai Yoshiko

Workers in the Cultural Revolution, Elizabeth Perry and Xun Li

The Chinese Triangle and the Future of the Asia-Pacific Region, Alvin So and Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao

Foreword

THIS IS AN ABSORBING ACCOUNT of Ainu life written by an Ainu striving to preserve his peoples cultural heritage and sense of nationhood. Unlike many accounts by outsiders, which impose predetermined socio-anthropological categories on indigenous cultures, Kayano Shigeru offers a living testimonial to the history, ethos, customs, beliefs, hopes, and aspirations of a people whose way of life has been undermined by successive waves of invasion of their homeland by the Japanese.

The authors candid account of the history of three generations of his family, and through them of a people, draws us into the world of the Ainu, enhancing our understanding of and empathy for a way of life that prizes the harmony of human society in nature. It vividly reveals the tribulations that the Ainu endured as the Japanese occupied their home (mosir, the quiet land) and barred them from the subsistence hunting and fishing that provided the foundations of society and culture.

The process of encroachment began hundreds of years ago with incursions by Japanese warlords. The loss of land and livelihood accelerated with the establishment of the Meiji state, which brought the Ainu homeland under ever more stringent control and sought to Japanize the Ainu while incorporating Hokkaid within the purview of an expansive empire.

Our Land Was a Forest recounts the story of a remarkable Ainu leader raised in an impoverished but culturally rich family, who ended his formal education after graduating from elementary school and as a youth earned his living as a forester. Eventually, drawing on cultural traditions he absorbed from the ballads his grandmother sang and the ancient legends she recounted, he dedicated his life to preserving Ainu heritage, values, language, arts, crafts, and customsincluding dance, song, folklore, and literatureand to restoring the land and rights of his people. As a writer, as founder-curator of an important Ainu museum, and as a political activist, he has played a central role in the rebirth of Ainu consciousness. Kayano Shigerus story is an invaluable record of a people and culture at the edge of extinction striving to preserve their integrity and their culture.

Mikiso Hane

Knox College

Translators Note

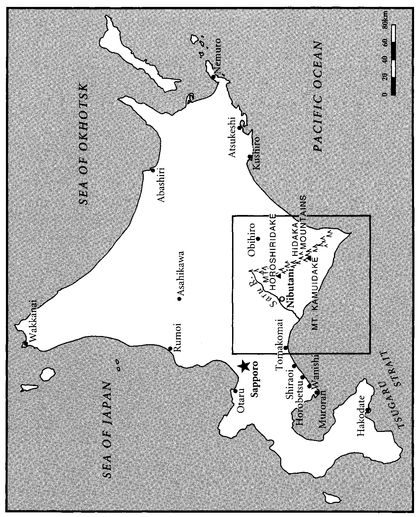

THIS PROJECT WAS UNDERTAKEN at the suggestion of Matsuzawa Hiroaki, then of Hokkaid University and presently of the International Christian University. Jane Marie Law of Cornell University read the entire manuscript with painstaking care and greatly improved the translation. Sasha Vovin of the University of Michigan assisted with romanization of the long quotations in Chapter 12. Kozaki Shinji checked the Ainu-language portions throughout the book and kindly provided romanization of all Ainu language portions of the text as well as syllable by syllable explanation. Sakurai Shin drew the two maps of Hokkaid and the illustrations of the family insignia of the authors ancestors who settled in Hidaka county. In the fall of 1992 and 1993, students in the third-year Japanese reading course at Cornell read excerpts from Chapter 6 in the original and added to the spirit of the translation. Alice Colwell and Michelle Asakawa of Westview Press refined the language and format of the book. The author, Kayano Shigeru, extended warm support from Nibutani and provided a new epilogue and photographs, including a treasured original portrait of his grandparents. Suzusawa Shoten, Tokyo, kindly granted us the use of eight drawings from their Ainu no mingu (1978).

In the text and Glossary, Japanese names are given in the Japanese style, with family names first. In Matsuura Takeshir, for example, Matsuura is the family name, Takeshir the personal name. The Ainu portions of the text were translated from the Japanese translations provided by Kayano Shigeru in the original version of the book; hence the translation may sometimes lack line-to-line correspondence with the Ainu. Minimal punctuation was added to prose sections of the originally unpunctuated Ainu text.

Kyoko and Lili Selden

The island of Hokkaid

Our Nibutani Valley

THE AZURE HORIZON spreads in all directions, not a cloud in sight. The pine grove on the opposite shore of the Saru River is dark, but everything else in the vast landscape is pure white, covered with snow. The first time southerners see this Hokkaid winter scene, they are likely to feel it would somehow be wrong to step into it. I myself felt such reluctance when I first went south and faced the grass that everywhere made the earth green.

Surveying the strikingly clear sky and the distant, dark pine grove across the river, I made my way over the bright snow to pay a visit to the ailing Kaizawa Turusino.

Standing in front of the old womans house, I noticed a hureayusni decorating the upper right corner of the entrance. Hureayusni, or a branch of raspberry, was used as a charm to ward off colds. When I was a child, if word spread that a cold was making the rounds of a nearby village, every Ainu family put up raspberry branches either at the entrance of their reed-thatched home or by a window.

Turusinos house, like all Ainu homes these days, was a modern cement-block building that resists the cold. Yet this woman in her nineties was unhesitatingly carrying out this long-forgotten custom. The sight of that single branch carried me back forty years to my childhood.