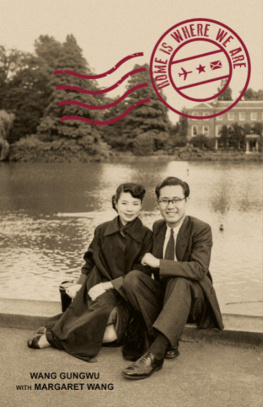

To my wife Margaret

Our children

Shih-chang (Ming), Lin-chang (Mei), Hui-chang (Lan)

and our grandchildren

Lisheng (Sebastian), Yisheng (Katharine), Kaisheng (Ryan)

and Feisheng (Samantha)

Why Tell

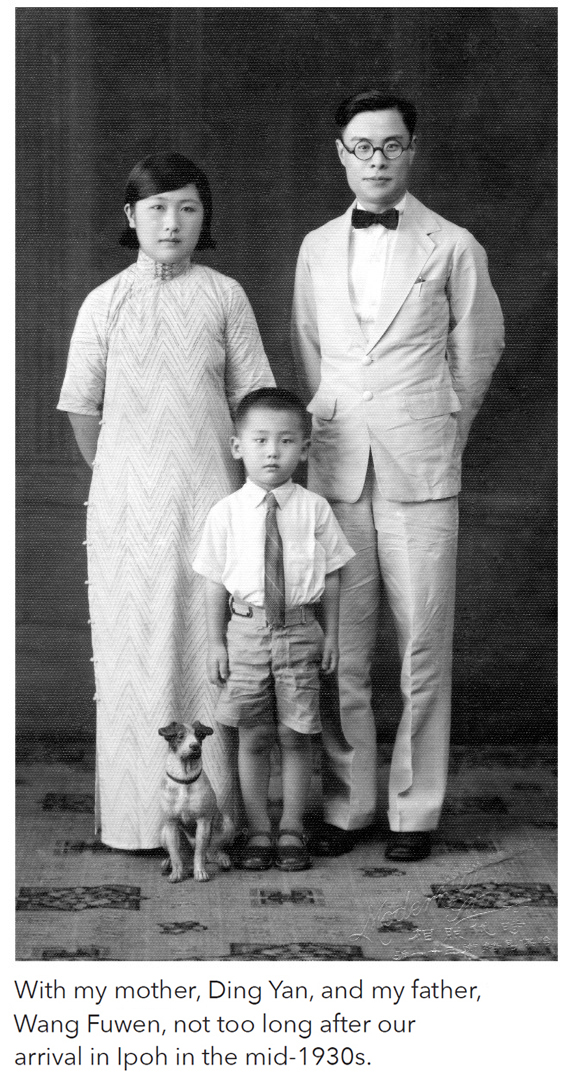

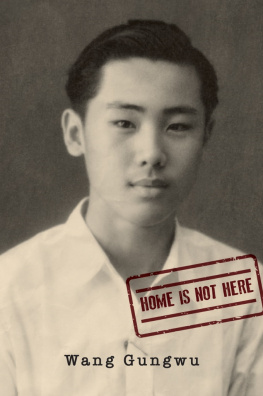

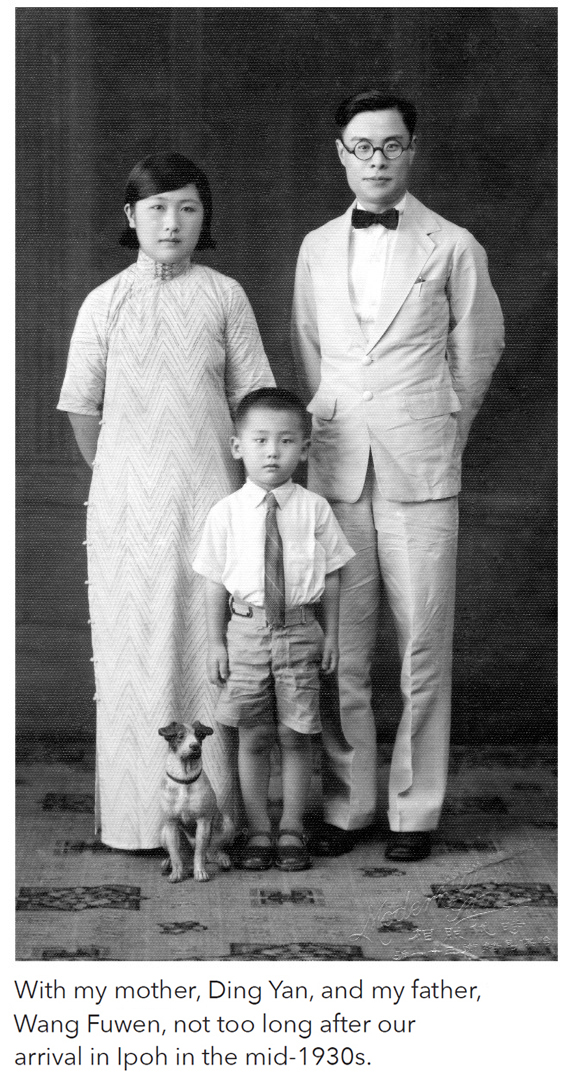

SOME YEARS AGO, I started to write the story of growing up in Ipoh for my children. I knew it was also for myself as I tried to remember what my parents were like. My childhood until I was nineteen, with the exception of nine months in 1948, was the only time when I lived with them in the same town. I thought I should tell my children how different my world was before I left home so that they would understand what has changed for them as children and for us as their parents. My wife Margaret knew my story and agreed that I should tell it while I could.

My decision to publish this story came about when I met a group of heritage activists in Singapore. They made me more conscious of the personal dimensions of the past. As someone who has studied history for much of my life, I have found the past fascinating. But it has always been some grand and even intimidating universe that I wanted to unpick and explain to myself and to anyone else who shared my desire to know. Even when I read about the lives of people high and low, I looked from a critical distance in the hope of learning some larger lessons from them. In time, I realized how partial my understanding of the past was. I was using a platform that was dominated by both European historiography and elements of my Confucian self-improvement background.

My heritage friends reminded me that, while we talk grandly of the importance of history, we are insensitive to what people felt and thought who lived through any period of past time. We often resort to literature to try and capture moments of joy and pain, and that can be a help to imagine parts of ones past. But we have too few stories of what people actually experienced. Focusing on local heritage is a beginning. Encouraging people to share their lives might follow. I began to think that what I wrote for my children could be of interest to people who are not family. So I set out to finish my story and have taken it to the time when I left Ipoh in 1949 to study at the newly established University of Malaya in Singapore. My parents moved to Kuala Lumpur after that and never went back to Ipoh. In preparing this account for a wider readership, I have revised and updated parts of the story wherever I could.

Many friends tell me that they wish they had talked to their parents more when they were alive. I remember thinking the opposite when I was in my teens. I thought that my mother talked too much about China and not enough about the things that I really wanted to know. Instead, I recall how I wished my father would tell me about himself, especially about his life as a child growing up in China along the Yangzi valley. My parents both loved their China very much and, as long as I can remember, they constantly dreamt of returning home.

China was strangely imbalanced in my mind. There was my mothers view of a traditional China that she was afraid would disappear. She wanted her only child to understand something of that. She saw it as her duty to let me know as much as possible because I was growing up in a foreign land.

I thought I should tell the story of how all that came about for my children to read. As I did so, I came to regret I did not talk more with my parents when they were still alive. My mother did finally write about her life and I have included here what I had translated for my children. I wish I had asked her to tell me more. But what I missed most of all was to hear my father talk to me about personal things, about his dreams and what it was like when he was growing up. I sometimes wished that he did not live so close to his ideal of a Confucian father and showed me something of his real self. I would have loved to know how he turned from child to adult in the turbulent times he lived through. Perhaps it is that sense of loss that has driven me to tell this story.

Before my mother died in September 1993, she left me with the manuscript of her memories of fifty years that she had completed in 1980. She had written it for me in her very neat xiaokai . She said that there were so many things about her life that she wanted me to know, but we had never sat down long enough for her to tell them to me. I read the memoirs with great sadness. There was so much about her life that I had missed by not hearing her tell me face to face. Using parts of her memoirs, I told Margaret and our children about some key moments in her life. When writing my story for our children, I then went on to translate for them to read the relevant parts of what my mother remembered. That would be more authentic. They would have the chance to see her words and thus have a better sense of the mother she was to me. When I decided to publish my growing up story, I thought I should also include her story as annexes to what I have written.

. She said that there were so many things about her life that she wanted me to know, but we had never sat down long enough for her to tell them to me. I read the memoirs with great sadness. There was so much about her life that I had missed by not hearing her tell me face to face. Using parts of her memoirs, I told Margaret and our children about some key moments in her life. When writing my story for our children, I then went on to translate for them to read the relevant parts of what my mother remembered. That would be more authentic. They would have the chance to see her words and thus have a better sense of the mother she was to me. When I decided to publish my growing up story, I thought I should also include her story as annexes to what I have written.

I cannot remember when my mother began to tell me her stories but believe it was even before I started school at the age of five. She did so to make me conscious of my family in China and thus prepare me for our return to China. She wanted to make sure that I would see the total picture of what she knew and therefore would know what to expect. If I had a sister, perhaps my mother might not have told me so much. But as I was an only child and she was far from her home and had no one else to tell her stories to, she made sure I would not forget what she told me. Ours was a first generation nuclear family. Both my parents grew up in extended families that lived under one roof among many close relatives of at least three generations. And other relatives lived nearby, so it was not normally necessary to say much about them.

My mother made sure I absorbed her stories because she told many of them again and again. It was a kind of cultural transmission exercise for her because I never felt that she told her stories for my entertainment. She always exuded a strong sense of duty in everything she did or said, and I soon realized that she was educating me about my identity as the son of my father and someone from families that were deeply rooted in traditional China. She wanted me to know my place in the Wang clan. She also wanted to do her duty as a Chinese mother to a son born in a distant foreign land.

My mother began with her own story. She was Ding Yan  , known within her family as

, known within her family as  . She was born in the county seat of Dongtai

. She was born in the county seat of Dongtai

Next page

. She said that there were so many things about her life that she wanted me to know, but we had never sat down long enough for her to tell them to me. I read the memoirs with great sadness. There was so much about her life that I had missed by not hearing her tell me face to face. Using parts of her memoirs, I told Margaret and our children about some key moments in her life. When writing my story for our children, I then went on to translate for them to read the relevant parts of what my mother remembered. That would be more authentic. They would have the chance to see her words and thus have a better sense of the mother she was to me. When I decided to publish my growing up story, I thought I should also include her story as annexes to what I have written.

. She said that there were so many things about her life that she wanted me to know, but we had never sat down long enough for her to tell them to me. I read the memoirs with great sadness. There was so much about her life that I had missed by not hearing her tell me face to face. Using parts of her memoirs, I told Margaret and our children about some key moments in her life. When writing my story for our children, I then went on to translate for them to read the relevant parts of what my mother remembered. That would be more authentic. They would have the chance to see her words and thus have a better sense of the mother she was to me. When I decided to publish my growing up story, I thought I should also include her story as annexes to what I have written. , known within her family as

, known within her family as  . She was born in the county seat of Dongtai

. She was born in the county seat of Dongtai