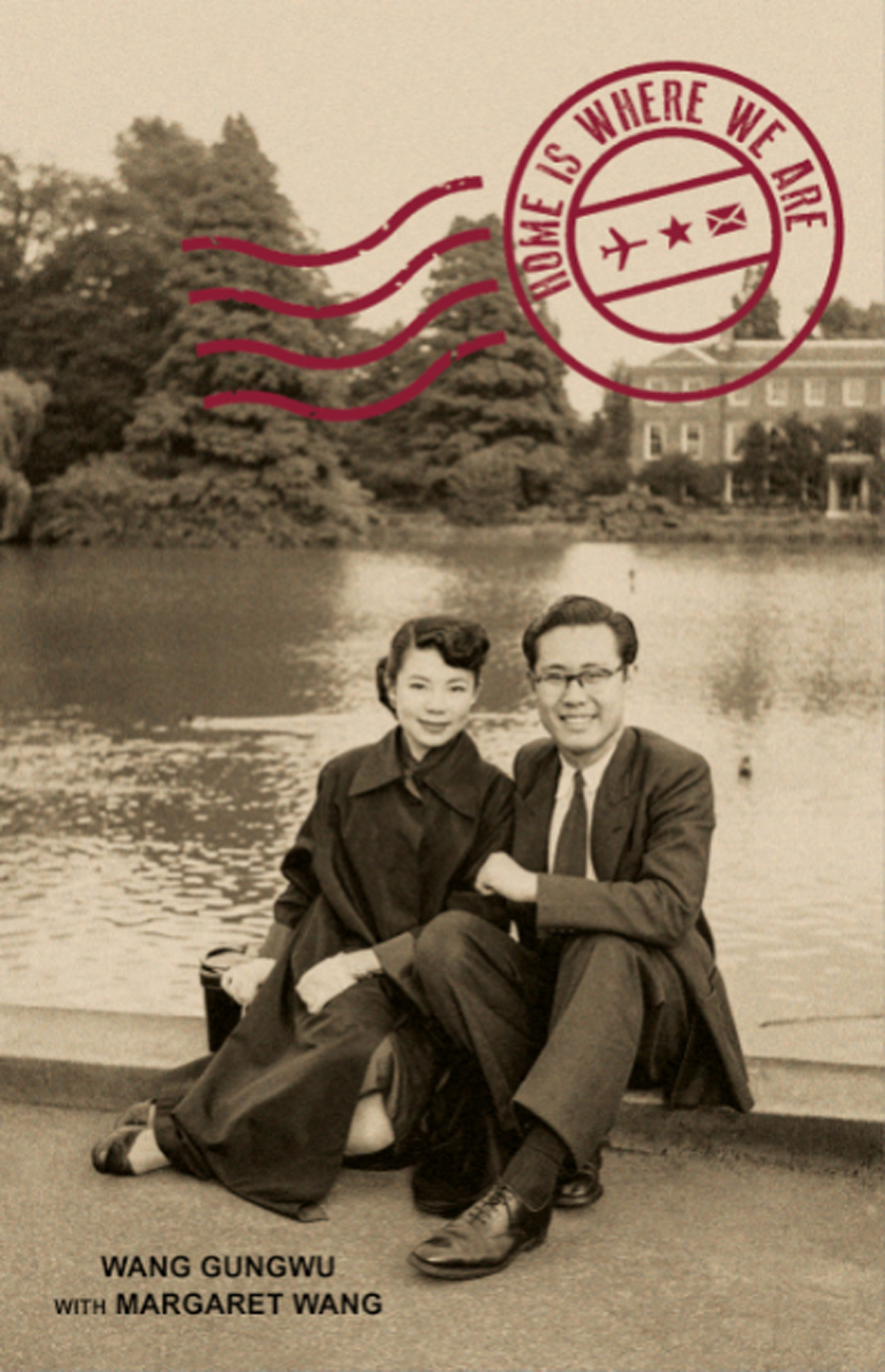

Home is Where We Are

Wang Gungwu

with

Margaret Wang

In Memory of Margaret departed 7 August 2020

Remembering our twenty years at the University of Malaya in Singapore and Kuala Lumpur and all our friends and colleagues who helped us find home

Contents

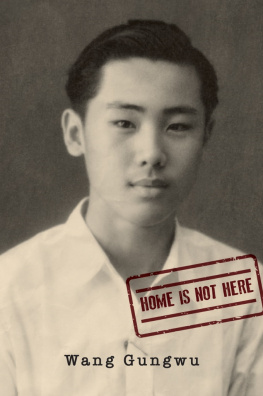

WHEN I WAS growing up, home meant China, the country my parents came from and to which we would one day return. We finally did when I was 16 years old. My parents, however, did not stay and left me to study at the national university in Nanjing. A year later, they asked me to rejoin them in Malaya when the Peoples Liberation Army was ready to attack Nanjing, the national capital. My book, Home is not Here (2018), ends when I was back where I started. My parents dream to return to the country they loved had ended. Their China was about to be revolutionized in ways they could not comprehend; they no longer talked about going home.

The British-initiated Malayan Union had become a protectorate of Malay States called the Federation of Malaya; the Emergency had been declared against the Malayan National Liberation Army organized by the Malayan Communist Party to liberate the country from British rule. My father saw his work as improving the quality of Chinese education and believed that the local Chinese community should stay out of Chinas politics. It seemed that he had decided to stay in Malaya and wanted me to have a new start.

I spent most of 1949 preparing to do that. It was a lonely time. My childhood friends had moved to Kuala Lumpur (KL) and my closest school friends were studying in Singapore, at the Raffles College and the King Edward VII College of Medicine. My hope was to continue my university studies. When it was announced that the new University of Malaya (MU) would bring the two colleges together, my father thought I could gain admission because of my Cambridge School Leaving Certificate. However, he was concerned that I might not succeed because I was Chinese and not local-born and, realizing that I could qualify, arranged for me to obtain local citizenship as a naturalized Malayan. Neither of us was conscious of this at the time but, by so doing, I continued to believe that home was tied to a country, in this case one that was yet to be born.

When I continued my story, I recalled that some time ago Margaret had written her story for our children. I asked her if I could weave parts of that into mine to augment and give colour to what I remember of our lives together. I am thankful that she readily agreed.

ON THE EVE of my 19th birthday, I acquired two new identities. I was a post-colonial undergraduate and a citizen of the Federation of Malaya. I was no longer a foreign Chinese in the eyes of the government and now had the opportunity to go on to learn in a university. In both identities, Malaya loomed large. And I spent the next twenty years of my life wondering how I could make Malaya my country.

I was lucky to have such a soft landing. My father made that possible because he was determined that his only child would not miss out on higher education simply because he had called me back from Nanjing. He could not afford to send me overseas again. When he learnt that MU was being planned, he saw that getting me admitted was the only way I could continue my studies. Fortunately, something he did in the years 194547 made that possible. This was when he postponed the familys return to China after the war ended so that I could finish my secondary education. That way, I would not have to start afresh in a high school in China to qualify to sit for a university entrance examination. He had therefore waited until my Cambridge School Certificate results were announced before we left Malaya.

Little did he know what a good decision that was. When we unexpectedly came back, the delay till the middle of 1947 to go to China helped me in two ways. The certificate I had received made me eligible to apply for admission to the new university in Singapore, and the extra two years staying on in Malaya also qualified me to seek Federal citizenship under the new constitution. Given that the anti-British war known as the Emergency was underway, my status as a Chinese national who was not local born, someone stateless, could have jeopardized my chances of being admitted. By that time, my father had become open to the idea that Malaya was where we could settle down. My parents never admitted it but I believe they anticipated the political fallout among local Chinese who supported the Republic of China (ROC in Taiwan) against those excited by the New China in Beijing and did not want me to be drawn to one side or the other. I also began to sense that they now thought that living in Malaya was better than anywhere else in the region.

The University of Malayas primary mission was to train locals to assist British officials in the work of administering their colonies and protectorates. This British-type university set out to transmit ideas and institutions that could help develop the future nation, ideally one that would have goodwill towards British interests. Young Malayans would be selected to take over when the colonial officers eventually left. This was an imperial cause that planned ahead for the end of Empire and its replacement by a new Commonwealth. To accomplish this task, graduates of Britains best universities were encouraged to go forth to teach in Malaya. It was understood that everything would be done to make MUs degrees recognized and its graduates useful.

***

The University was formally inaugurated on 8 October 1949. Malcolm MacDonald, the Commissioner General for Southeast Asia, conducted the opening ceremony. Present were Malay monarchs or their representatives as well as political leaders from all parts of the Federation of Malaya and the Colony of Singapore. That campus was renamed University of Singapore in 1962 and then National University of Singapore in 1980. In 1999, when it celebrated the 50th anniversary of its foundation, I described the university as having had a head start preparing for a post-colonial world. At the time, events in Malaya were pointing to some testing years ahead. We were alerted to ready ourselves for major transformations in the region. I suggested that, at the Foundation Ceremony, there was already an air of expectation that this was an institution that would play an important role in the building of a new nation.

The students were new to the idea that Southeast Asia was a region. They were the products of colonial education. The textbooks we used were more or less the same across all the schools in the British Empire and Commonwealth. All students matriculated with certificates provided by the Cambridge Examination Board. As preparation for a future Commonwealth centred in London, the system was skillfully designed, and did the job well. But, as a result of that standardization, most of us arrived at the new university knowing little about Malaya and the countries in the neighbourhood. I was even worse off than most because only half of my education was at a school that looked to England, with the other half being done at a home that focused on the ideal world of ancient China. In addition, my school education was truncated by the Japanese occupation.

Our British teachers hardly knew any more about Malaya. There were a few exceptions among those who had taught in Raffles College before the war and survived three and a half years in Japanese prisons. Not surprisingly, geographers like E.H.G. Dobby led the way. He produced the first geography textbook on the region, which highlighted the strategic importance of Southeast Asia to Britain. Also, there were some in the Economics Department who concentrated on aspects of the Malayan economy, seen as vital to Britains post-war recovery. T.H. Silcock, in particular, took us through the most recent studies concerning Malayas tin and rubber industry. In the field of history, Brian Harrison produced the first book on the history of Southeast Asia although it was quickly supplanted by a more comprehensive work by D.G.E. Hall, the former professor of history at Rangoon University.