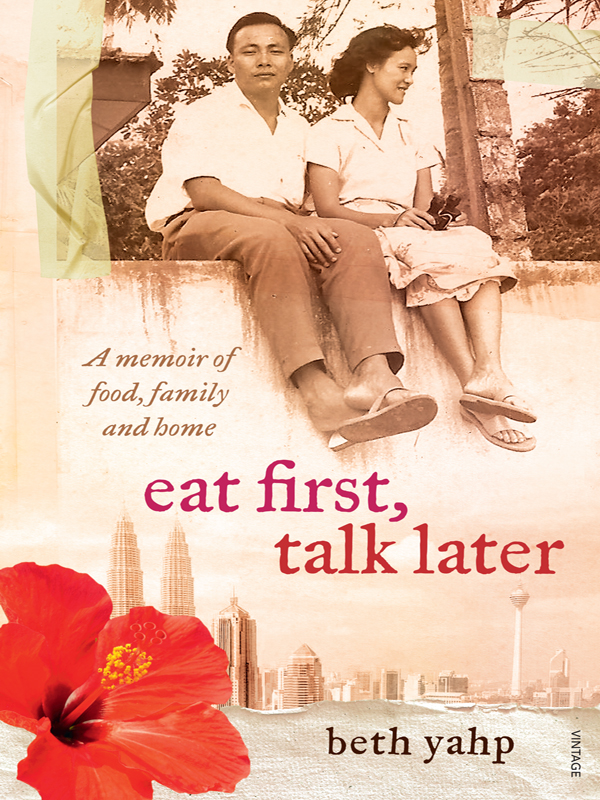

About the Book

In this dazzling memoir Beth persuades her ageing parents on a road trip around their former home, Malaysia. She intends to retrace their honeymoon of 45 years before, but their journey doesnt quite work out as she planned. Only the family mantra Eat first, talk later keeps them (and perhaps the country) from falling apart. Around them, corruption, censorship of the media, detentions without trial and deaths in custody continue. Protests are put down, violently, by riot police.

Her parents argue, while, lovelorn after the end of a grand amour in Paris, Beth tries to turn their story into a Technicolor love story for the big screen. Meanwhile, shes embroiled in a turbulent relationship with an opposition activist, Jing, who is at the forefront of the democratic struggle for change.

Eat First, Talk Later is a beautifully written, absorbing memoir that moves between Australia, where Beth lives, and Malaysia a country considered one of the multiracial success stories of South-East Asia, with many fascinating, yet deeply troubling, sides to it. Its a book about how we tell family and national stories; about love and betrayal; home and belonging; and about the joys of food.

All their friends in Kuala Lumpur are retired, coming into a kind of second blossoming. My parents, Peter and Mara, are just tired. Mara says so, often, while Peter smiles like a Buddha. He watches a swarm of motorbikes sliding through the traffic, the straps on someones helmet dangling, a passengers fluorescent-pink headscarf whipping past. He points his chin at Mara, who is panting quietly in the back seat. Jetlag lah, he explains.

Wah, long trip, Mara agrees.

Despite the aircon, tiny beads of sweat pepper her forehead. Shes gripping her seatbelt with both hands as I reverse. She smiles encouragingly, then blurts, Aiya why so fast?

I slam the brakes. Beside me, Peter slams imaginary brakes.

Careful! he instructs. KL drivers!

Never give chance, Mara adds.

I start inching my way out again, into a flurry of honks and beeps. Cars swerve to other lanes as I swing the steering wheel one-handed, nudging our borrowed LandCruiser into the relentless stream. I barely avoid an overloaded lorry, breezing by in one beeping screech. Sun-darkened workers dangle over its sides, whooping, flapping their hands.

This time I dont hesitate. Im anxious to get going. We have to hit the road out of Kuala Lumpur soon, before traffic builds up too much. Before it starts to rain. Before Peter and Mara succumb to jetlag for another day, or the urge to visit another friend or relative they havent seen in years. Before they remember another errand we have to run.

Weve already changed our route twice, delayed our road trip by three days. Were now heading north, up the west coast of Malaysias peninsula to Penang instead of east to Kuantan, where Id believed until a week ago that my parents had spent their honeymoon. Were on their second honeymoon, at least thats what Ive told them. As usual, when I told them Peter and Mara just blinked at me.

Ive been in Kuala Lumpur a few nights already. A few nights, and Ive touched base with Jing and the other activists; Ive helped launch a banned book and stood watching a sit-in. A few days, and Ive already checked out nearly every favourite restaurant, scoffed any number of favourite hawker meals.

Already my aircon dreams are of swimming through air like water. One night I dream the bedroom window grille is prised from its moorings, the window thuds open and a wave of black shapes enters. They shout, kicking the furniture. They flash their torchlights into the darkest corners of the room. I try to rise, as Im ordered, but am somehow anchored to the bed. Im sloshy, the weight of an ocean inside me. I wake wheezing through my own jetlag. I drive Jings car around the city, minding speed limits, dithering at every crossroad. I miss all the green lights.

Go! Jing throws up his hands. Go, go, go!

Already my arms are criss-crossed with musang scars: his pet civet cats claws and kisses. I wear long sleeves to cover them up before Peter and Mara arrive.

For a trip as anticipated as this, theres been hardly any preparation. Everything seems to have fallen into place at the last moment, an itinerary drawn up a couple of weeks before my parents departure from Honolulu, where they now live. A list of possible questions scribbled into my notebook in Sydney, a couple of days before I leave.

What favourite recipe did you find in Gombak, Mum? In which town did you learn to make achar cucumber pickle that stained my fingertips turmeric yellow and never passed the Australian customs officers jaundiced glare? What was it like for your family during the Japanese Occupation? When was the first time you saw Dad? Can you remember? What was it like growing up in a Chinese New Village, Dad? On your sales trips to the interior, which town was the most famous communist black spot? What did you eat there? When was the first time you saw Mum?

I dont ask them which town they honeymooned in, because I think I already know.

I fold the corner down on the page with these questions, and never look at them again.

We have been circling the idea of a trip together for what? a year now? Eighteen months? But only in the way things are talked about in my family, half a suggestion here, the hint of something deeper there, and the usual answer, Well, lets see

Dont you want to go back to Malaysia? I ask when I visit them in Hawaii.

Yes, of course. As usual, my mother turns to me, or one of my sisters, as soon as my father is out of earshot, a distance that over the years has crept closer and closer to wherever were standing. Leaning forwards, she launches into her undertone. Peters hearing ability goes up and down, and now we cant really tell whether hes putting it on, or has learned to lip-read.

Your father was so shocked the first Chinese New Year here, Mara whispers. Now hes so sad every year. You should see him. Of course he wants to go back. Can you imagine the shock, when he had to go to work the first Chinese New Year in Honolulu, the first time in his life? For one month before, he came home every day, very grumpy. I didnt dare ask what was wrong. When hes like that, no use talking. Leave him alone. I just keep quiet. One day he said, Whats wrong with these people here? They are Chinese! Here, its business as usual. No fuss. No angpow, no firecrackers like KL. Another day he came home, sat down, and said, They are American.

So, what are you now, Dad, Chinese or American?