Contents

Guide

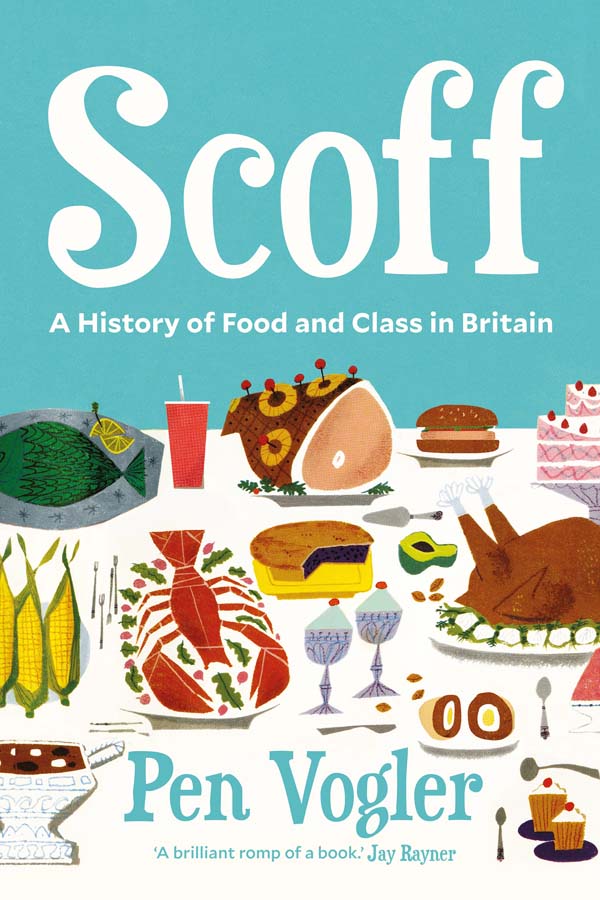

Also by Pen Vogler

Dinner with Mr Darcy

Dinner with Dickens

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2020 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Pen Vogler, 2020

The moral right of Pen Vogler to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78649-647-8

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-648-5

All illustrations copyright Dan Mogford, 2020

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Simone, Miranda and Justin

With love

Introduction

Scoff1verb to jeer at

Scoff2noun food; a meal

The Chambers Dictionary

T WO YEARS AFTER the fall of the Berlin Wall, I was teaching English in a small town in what was then Czechoslovakia. The people of Liberec, twenty miles north of Prague, were blinking in the light of new problems and freedoms, such as the right to learn English and travel. None of my kind and respectful adult students had had the chance to discover Britain or any part of the West for themselves and they were courteously eager to learn everything my twenty-two-year-old self could impart. When I came to the lesson on British food in my TEFL book, I was a little apprehensive. Would all the books talk of roast beef and fresh vegetables make it look as if I was crowing, I wondered, to people whod been stuck behind the fried cheese and pickled cabbage curtain; and where I had seen no fresh fruit and vegetables in the whole of the winter months I had been there? I neednt have worried; they all already knew for a fact that British cooking was the laughing stock of Europe. No matter what I said about home cooking, local ingredients, international cuisines, I could see that they were having none of it. In spite of my inability to grasp the Czech language, I could tell a room full of scoffing students when I saw one.

Admittedly our international standing in the kitchen has, historically, never been good; no British chefs have given their names to the great dishes of cream, truffle and potato; the fame of British cakes tends to be domestic, unlike the Continental Torte families of Sacher, Linzer It has been, right up to our current culinary obsessiveness, a centuries-old belief of our Continental friends and many Brits themselves that the British are insufficiently obsessed with food and that a bit more European-style passion would bring us more enjoyable meals, a more functional family life, better health and fewer laughable cafs and restaurants.

However, one classic British obsession has given us a huge stake in the business of food, and that is social class. In a country where even letters have a choice of first or second class in the postal system, how much more ideal is eating, with its innate social function and attendant rituals, as a way of firing up rivalry, envy and social unease and conveying the niceties of where we all sit on the social ladder.

How we serve food and how we eat it, our table manners, what we call our meals and what time we have them, all this has been a source of immense fascination to Brits for longer than our European friends have been taking sideswipes at grey mincemeat and lumpy custard. Everything we believe we choose to eat actually comes to us with years often centuries of valueladen social history. Our decisions about what we like and how we regard food are influenced by our parents, their parents, our peers, but also by a long history and a wide network of social and political pressures. Foods have slid up and down the social scale, been invented or disappeared completely.

Most Brits could read a shopping basket as though it were a character sketch: Golden Shred or Oxford Marmalade; Typhoo or Earl Grey; Custard Creams or Florentines; Kingsmill or sourdough; stir-fry veg or Pot Noodle; battery or free-range; doughnuts or Chelsea buns. By the same token, how we behave at home isnt simply a matter of personal choice, but a series of clues about our background and upbringing. Whether you sit round the table as a family; how you push your peas onto your fork; whether you serve food, such as wild garlic or grouse, that hasnt English novelists use food to tell us something about the status of their characters: Austen mocks vulgar Mrs Bennet for obsessing about her well-cooked partridges, whereas David Copperfields obsession with batter pudding is pitiable not laughable, because he is hungry for food, for family and for security.

We take it for granted that more choice and refinement in food comes with money and social prestige, but it is determined by where and when you happen to be eating. Archaeologists believe they have pinpointed the emergence of what the sociologists call a differentiated cuisine to Ancient Egypt, where a high and low cuisine grew up alongside more sophisticated cultivation, food surpluses, wealth and power. There are no shortage of theories about why on earth early humans abandoned the fun and protein of a hunter-gatherer society for the back-breaking life of agriculture, but caste came early into the mix. Either a powerful, male elite organised matters so that they alone had access to the land and animals required for hunting, forcing the weaker members of the community to grow their own food; or and the difference is subtle but significant the men who chose or were chosen to hunt for food for the tribe gathered around themselves an aura of power. The association of hunting with aristocracy is ancient but not universal; the Indian caste system focuses on purity of food, with meat being less pure and therefore lower caste, so to move upwards meant becoming more vegetarian. Many parts of Africa still have a single cuisine, in which a whole community will eat porridge, meat soup, served with a relish made from okra, ground-nuts,

In our northern climate, the great differentiation was initially simply meat versus non-meat. The Norman overlords had the choice of several different types of meat (or fish on a fast day), but there was not much complexity at a feast; and perhaps because there was a limit to how much roast boar, venison, pheasant, hare, crane, heron, seal or porpoise one Lord of the Manor could put away, he came to demand more show and sophistication from his kitchens. This, of course, caused its own problems and the Tudor feast was marked by a series of distinctions: the higher up the table you were, the more variety you were permitted. It was a hard boundary to police, though. Ecclesiastical abstinence constantly tipped over into enjoyment and appetite, so in 1541 Archbishop Cranmer decreed the number of dishes which each rank in the clergy could eat from; unsurprisingly, after two or three months, by the disusing of certain wilful persons, it came again to the old excess, he reported glumly.