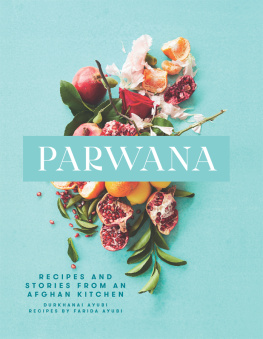

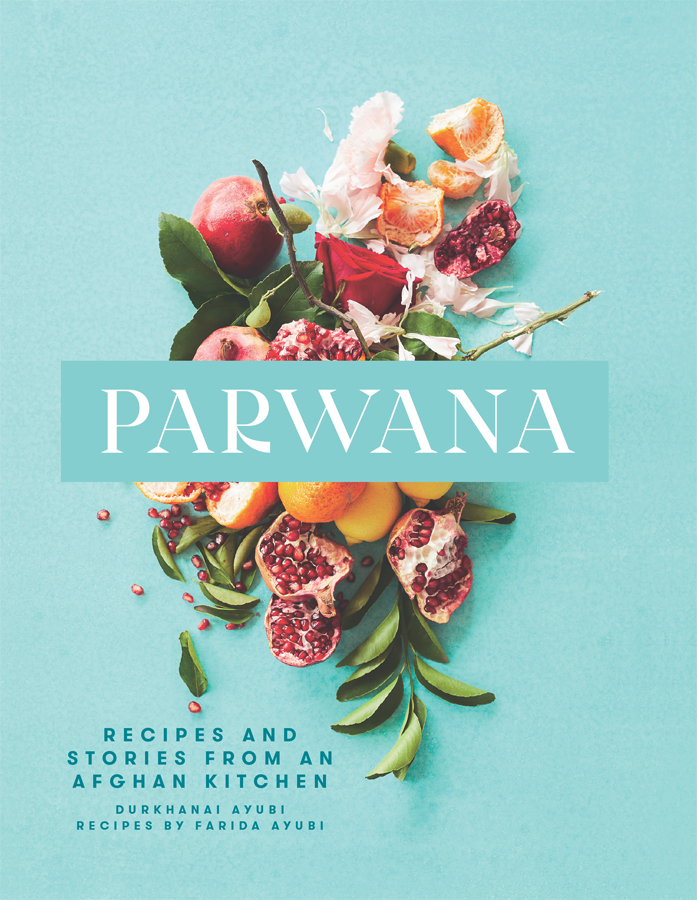

Interwoven with traditional Afghan recipes is one familys story of a region long afflicted by war, but with much more at its heart. Author Durkhanai Ayubis parents, Zelmai and Farida Ayubi, fled Afghanistan with their young children in 1985, at the height of the Cold War.

When their family-run restaurant Parwana opened its doors in Adelaide in 2009, their vision was to share with the world their family memories through the delights of Afghan cuisine, infused with Afghanistans rich historical culture and traditions of generosity and hospitality, to offer a more complete picture of the country they had left behind.

These fragrant and flavourful recipes have been in the family for generations and include rice dishes, dumplings, curries, meats, Afghan pastas, chutneys and pickles, soups and breads, drinks and desserts. Some are everyday meals, some are celebratory special dishes. Each has a story to tell.

PRELUDE

What you seek is seeking you

Rumi, thirteenth-century Persian poet and theologian

My family never had any grand plan to be in the restaurant game. Parwana began with my mother Farida (pictured left) and her intuition that, as migrants to Australia, it was increasingly important that we preserve the customs, flavours and essence of our Afghan cuisine, and also share it with those in our new home. She carried with her a generationally engrained love for her traditional food and the rituals that sit alongside it. This, combined with our experience as displaced people, witnessing first-hand the scattering effects of war on Afghanistans memory and culture, coaxed Parwana into being. In this way, Parwana was driven by commemoration, reconciliation and creativity, tinged with a mixture of loss and hope.

However, in hindsight, the strands of the idea had long existed in many guises, and had been finding their way to us to consolidate and express, well before we opened the doors to Parwana in 2009. The restaurant, and the food we shared, was a manifestation of the immense history of cross-pollination and cultural exchange that underpinned Afghanistans history at the centre of the ancient Silk Road. As time marched on and change unfolded on the land, including the emergence of Afghanistan as a nation state, this was captured in the cuisine and the traditions surrounding it. By the time the heavy clouds of conflict gathered overhead, my family had migrated to Australia and, with the emotions of exile, whose challenges and opportunities were now ours to carry, food took on a new poignancy and significance. Food was never static, but an ever-evolving way to stay anchored to our history while filling our sails with hopes for tomorrow. For us, food had become a means to tell a bigger story. This book contains not only recipes, but also the history and energies that lie behind them.

An awareness of these histories and energies is important, even necessary, for understanding Afghan cuisine in a way that extends beyond the superficial. For too long the dominant narrative surrounding Afghanistan has been trapped in the idea of its conquest, taming and manipulation by those who seek to control it. Images of violence and catastrophe almost always prevail. The inference in all these images is one of a nation far too hostile and foreign, too other, to engage with, or a wasteland to be pitied. And, although it is true that many Afghan people have suffered over generations, the reasons for this suffering are intimately linked to prevailing narratives that consign and reduce the region, and the people in it, to a position that is distant and irreconcilable.

But the truths about Afghanistan that are becoming increasingly pertinent to understand, against the globally intertwined reality of our world today, are the stories of the interconnection that underpins it. The way in which this interconnection has been captured in the food, ingredients, flavours, rituals and experiences of my family, I hope to unfold in the pages of this book. Furthermore, in Afghan custom, where historical ties run deep and form the lens through which the world is first understood, the stories of food and culture have been threaded together, wherever possible and relevant, by the genealogy of my mother, whose quiet resolution and love for cooking ultimately brought Parwana to life.

Parwana, and the cuisine it shares, hold many layers of significance for us. Both tell a story of the unexpected as those who dine on Afghan food for the first time find themselves surprised by the familiarity of the dishes, hinting at a rich and interconnected history untold. They tell the story of my mother, who lost her own mother at the age of four and was raised by a father who encouraged her to pursue her love of cooking from a young age. They tell the story of an irrefutable need to ritualise through food, of the permanent and deeply carved imprints of memories otherwise transient and fleeting. They tell the story of who we have come to be, sculpted into shape by the emotional and cultural evolutions we remained attuned to. And, importantly, they tell the story of how we experience firsthand, through food and Parwana, a universal desire to connect, irrespective of perceived differences hinting at a vision of a future into which we can all move forward together.

THE CROSS-POLLINATION UNDERPINNING CIVILISATION

Your spirit is mingled with mine as wine is mixed with water; whatever touches you touches me. In all the stations of the soul you are I.

Al-Hallaj, tenth-century Persian poet and Sufi

My family story, and that of Parwana and the food we share, is the product of millennia of globally significant history that precedes us. In our world today the imagination of many is held captive by the firmly engrained idea of an irreconcilable schism between East and West, but somewhere beyond this reduced narrative lies a rich and intertwined history.