The Day the Sun Died

The Years, Months, Days

The Explosion Chronicles

The Four Books

Lenins Kisses

Dream of Ding Village

Serve the People!

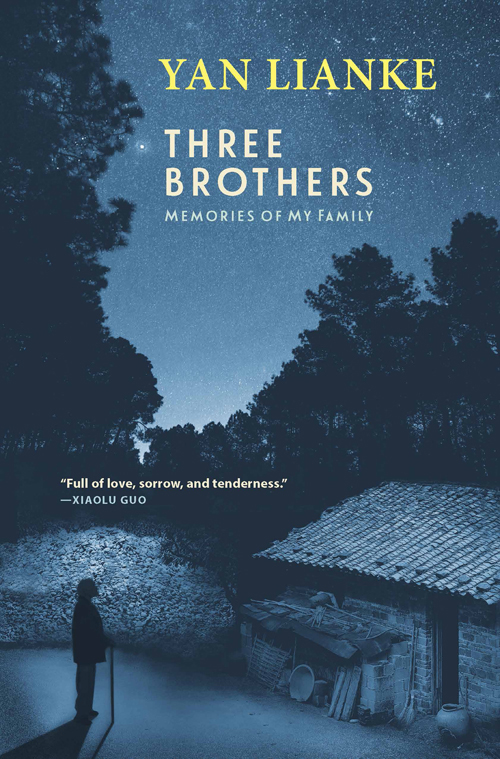

YAN LIANKE

THREE

BROTHERS

Memories of My Family

Translated from the Chinese by Carlos Rojas

Copyright 2009 by Yan Lianke

English translation 2020 by Carlos Rojas

Cover design and collage by Gretchen Mergenthaler

Cover images: house Bigstock; man Hongqi Zhang/Alamy; sky Stocktrek Images, Inc./Alamy

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or permissions@groveatlantic.com.

Three Brothers was first published in China in 2009 by Yunnan Peoples Press as Wo yu fubei.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

First Grove Atlantic hardcover edition: March 2020

This book is set in ITC Berkeley Oldstyle with Adobe Caslon Pro by Alpha Design and Composition of Pittsfield, NH.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

ISBN 978-0-8021-4808-7

eISBN 978-0-8021-4809-4

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

20 21 22 23 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Some people spend their entire lives in their own home, village, or city, while others spend their lives elsewhere. There are also some people who end up constantly traveling back and forth between home and another place.

When I was twenty, I left home to join the army. This was the first time I took a train, the first time I watched television, the first time I heard about Chinese womens volleyball, and the first time I had the chance to eat limitless amounts of dumplings and meat buns. It was also the first time I learned that there were three categories of fiction: short stories, novellas, and novels. It was also back in 1978, while I was living in the military barracks, that I became enthralled by the solemnity and even the smell of Chinas literary journals, Peoples Literature and Liberation Army Literature and Arts. It was around this time that I happened to see, on the cover of a book in the city library, a picture of the blue-eyed Vivien Leigh. I was shocked by her beauty, and for several minutes I stared dumbfounded at the picture. I couldnt believe that foreigners looked like this, that there could be people in this world who appeared so different from us. So I checked out all three volumes of the Chinese edition of Margaret Mitchells Gone with the Wind, each of which had a cover with a picture of Leigh from the film adaptation, and over the course of three nights I finished the entire thing. I had assumed that the rest of the worlds fiction was identical to the revolutionary stories and the Red Classics that I had read, and this was how I came to realize how limited and warped my understanding of literature was.

I began excitedly reading works by Western authors such as Tolstoy, Balzac, and Stendhal. While reading Hugos Les Misrables, I felt my palms grow sweaty, thinking that Jean Valjean might step out from the books pages, a thought that was so disturbing that I frequently had to close the volume and crack my knuckles just to distract myself. Similarly, while reading Flauberts Madame Bovary, I would wake up in the middle of the night and go out to the military drill grounds, and only after running a lap in the frigid cold would I return to my dormitory and continue devouring the novel. But it was Margaret Mitchell who truly transported me to another world, a casually dressed maid leading me into a solemn church.

It was at this time that I began to commit myself to reading and writing, and even submitted manuscripts for publication. In 1979 I published my first short story, which unfortunately is now lost. For that work, I received eight yuan, which made me more excited than an 800,000 yuan payment would today. I used two yuan to buy candy and cigarettes for my company and platoon leaders, as well as my fellow soldiers. Then I pooled the remaining six yuan with the earnings Id saved up from the preceding three months, leaving me with a total of twenty yuan, which I mailed home to help pay for Fathers medicine. Over the next few years I managed to publish one or two stories a year, from which I earned between a dozen and several dozen yuan. I sent almost all of my payments home, and Mother or Elder Sister would give the money to the town pharmacy or hospital for Fathers medicine and treatment. Eventually I was promoted to cadre and got married, but I secretly still dreamed that one day I might be able to become an author. If I did, Father would feel that I had truly succeeded in establishing both a career and a familymeaning that he could now depart from this life.

The same way that a tree can bear fruit, and the fruit can decay, die, or yield a new fruit tree, over time, a single household can grow into a village. Everything is merely a repetition or a reenactment of this same basic process of growth. Regardless of whether you spend your entire life on a single plot of land or leave home and seek your fortune elsewhere, it is impossible to escape your destiny.

I never stop to ponder things beyond fate, because accepting fate is my only way of approaching the world. When Father told me to go seek my fortune, I began struggling to achieve that fortune. When Margaret Mitchell showed me a new world, I began exploring it. I set about reading and writing, establishing my career and earning money, and when I was tired I would return to my family home and chat with my mother and my siblings, and do what I could to help out the other villagers. After recovering my strength I would leave again, only to return when I was tired. I believe that this process of traveling to and from the village is a trajectory arranged for me by heaven.

In 1985, my son was born, and my mother moved from our hometown in the countryside to the old city of Kaifeng, to help with the baby. That also happened to be the same year that I published my first novella in the now-defunct journal Kunlun. Running just under forty thousand Chinese characters, the novella earned me almost 800 yuan, and our family was almost more excited to receive this vast sum than we had been by the birth of our son. To celebrate, the entire family went to a restaurant and wolfed down a meal, and we also purchased an eighteen-inch television set. From the 1979 publication of my first short story to the 1985 publication of my first novella, I had endured six years of hardship and toil, and my family understood how this was bittersweet. Mother, however, took that thick copy of