Contents

CHILDREN OF UNCERTAIN FORTUNE

The Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture is sponsored by the College of William and Mary. On November 15, 1996, the Institute adopted the present name in honor of a bequest from Malvern H. Omohundro, Jr.

2018 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

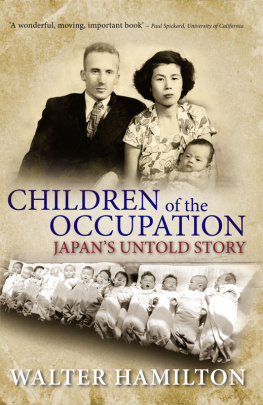

Cover images: Top: Lady Elizabeth Murray and Dido Belle. Unknown artist, formerly attributed to Johann Zoffany. Circa 1780. Courtesy of Earls of Mansfield, Scone Palace, Perth, Scotland. Bottom: The Morse and Cator Family. By Johann Zoffany. 1784. Image courtesy of the Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums Collections.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Livesay, Daniel, author.

Title: Children of uncertain fortune : mixed-race Jamaicans in Britain and the Atlantic family, 17331833 / Daniel Livesay.

Description: Williamsburg, Virginia : Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture ; Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017030142| ISBN 9781469634432 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469634449 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Great BritainRace relationsHistory. | JamaicaRace relationsHistory. | Racially mixed peopleJamaicaSocial conditionsHistory18th century. | Racially mixed peopleJamaicaSocial conditionsHistory19th century. | Racially mixed peopleGreat BritainSocial conditionsHistory18th century. | Racially mixed peopleGreat BritainSocial conditionsHistory19th century. | Racially mixed peopleCivil rightsJamaicaHistory18th century. | Racially mixed peopleCivil rightsGreat BritainHistory18th century. | Racially mixed peopleCivil rightsJamaicaHistory19th century. | Racially mixed peopleCivil rightsGreat BritainHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC DA125.A1 L57 2018 | DDC 305.23089/0596009041dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030142

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

For Mary

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The list of acknowledgments is inevitably long for a first book. I have been the lucky recipient of an incredible amount of assistance, support, and encouragement since beginning this project. Generous funding from a number of different organizations enabled me to undertake research and writing. The History Department at the University of Michigan supported me throughout the whole of graduate school. A Pre-Doctoral Fellowship and Rackham Humanities Fellowship, along with summer funding from the International Institute and the Center for European Studies at the university helped significantly. The Institute of Historical Research at the University of London and the North American Conference on British Studies both provided funds allowing me to spend significant time in archives throughout the United Kingdom. A Fulbright Fellowship to Jamaica was instrumental to work through the fantastic repositories on the island. Short-term grants from the Huntington Library, the American Philosophical Society Library, McMaster University, and the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies broadened the scope and increased the depth of the project. A National Endowment for the Humanities Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Omohundro Institute in Williamsburg, Virginia, not only allowed me to finish important sections of research but also helped me to reconceptualize and rewrite the book in ways I never could have done by myself.

The archivists who diligently dragged out countless boxes, pamphlets, and books were key in undertaking this research and vital in discovering crucial corners in the sources that were completely blind to me. My deepest thanks go to Barbara DeWolfe at the William L. Clements Library who first hired me to sort through the Tailyour Papers that formed the foundation of this project. Robert and Sally Tailyours assistance with the correspondence, along with their hospitality in hosting me in their Somerset home, allowed me to understand their familys wider history. Librarians at the Jamaica Archives, the Island Record Office, and the National Library of Jamaica were patient, kind, and helpful as I stumbled my way through their vast holdings. The archivists at the National Archives of Scotland also opened the channels of communication to consult private papers throughout the U.K. Those records form a key part of this study. The Montgomery and Compton-Maclean families were especially generous to let me read their private letters, and Sir William Macpherson was exceedingly hospitable, opening his house and library to me in Blairgowrie. I greatly enjoyed our daily lunches while on break from reading his family papers. Finally, I owe a great deal of gratitude to the nearly anonymous workers at the British Library and the National Archives of England who dutifully called up so much material.

Before the project was even a thought in my head, though, I was unbelievably fortunate to come under the guidance of Fred Anderson. Although I was entirely ignorant at the time of how unusual it was for an undergraduate to receive so much mentorship and personal attention, I have since strived to emulate Fred as a teacher, scholar, and human being. My fortune continued in graduate school under the direction of David Hancock, who was equally generous with his time and supervision. David taught me never to be comfortable with my own assumptions or too quick to think that I had solved a particular problem. If this book has been successful in uncovering a group of silenced voices, it is owing to Davids help, guidance, and willingness to apply pressure when needed. Julius Scott and Michael MacDonald were also exceptional advisers on my dissertation and gave careful and thoughtful comments at every stage. Scotti Parrish, Dena Goodman, Martha Jones, Tom Green, Sonya Rose, Damon Salesa, Sue Juster, and Kali Israel gave great instruction and feedback in my initial inquiries as well.

A number of scholars have been exceedingly generous with their advice on this project. David Lambert, Zoe Laidlaw, Peter Marshall, and Deborah Cohen all contributed critical mentorship and feedback on early work. The faculty and graduate students at the University of the West Indies, Mona, helped me to sort through archival surveys in Jamaica. The late Glen Richards kindly invited me to present twice to the university. His advice, along with that of Sir Roy Augier, Swithin Wilmot, Kathleen Monteith, Dave Gosse, and Jonathan Dalby pointed me in the right directions for a successful stint on the island. Perhaps most importantly in Jamaica, James Robertson helped me to navigate the archives and was a terrific fellow passenger on rides out to Spanish Town. A book prospectus seminar at the Omohundro Institute gave me more help than I deserved once the dissertation was finished. Sarah Pearsall offered invaluable criticism about how to rethink the book. She has been an ideal mentor since, and I owe her tremendously for her guidance and help. Barry Gaspar, Karin Wulf, and Phil Morgan each helped me to refine those ideas even more and to apply them more specifically to the Caribbean. Likewise, Paul Mapp, Greg OMalley, Molly Warsh, Jonathan Eacott, Kris Lane, Amanda Herbert, Olwyn Blouet, and Chris Grasso gave critical feedback that enriched my thinking about the book. Finally, a number of scholars of Atlantic and Caribbean history have provided incredibly important comments on my work over the years. Alison Games, Peter Mancall, Kathleen Wilson, Gad Heuman, Christer Petley, Carla Pestana, Brett Rushforth, Michelle McDonald, Rob Taber, Carole Shammas, Bernard Moitt, Roderick McDonald, and Nicholas Popper have each helped to shape my ideas in fruitful ways.