Names: Goldthwaite, Melissa A., 1972 editor.

Title: Food, feminisms, rhetorics / edited by Melissa A. Goldthwaite.

Description: Carbondale : Southern Illinois University Press, [2017] | Series: Studies in rhetorics and feminisms | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016044017 | ISBN 9780809335909 (pbk.) | ISBN 9780809335916 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Food writing. | Food in literature. | Feminist literature. | Food writersBiography.

Printed on recycled paper.

One of the pleasantest of all emotions is to know that I, I with my brain and my hands, have nourished my beloved few, that I have concocted a stew or a story, a rarity or a plain dish, to sustain them truly against the hungers of the world.

M. F. K. Fisher, The Gastronomical Me

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Ideas often come from conversations around tables. The idea for this book came in October 2012 on a day of celebration with a house full of friends, family, food, and drink. Im grateful to Cheryl Glenn and Jennifer Cognard-Black, who were both there to celebrate with me that day, and who both had a hand in shaping this project. My thanks to Jennifer, again, and the other contributors who wrote, revised, and helped turn an idea into a book.

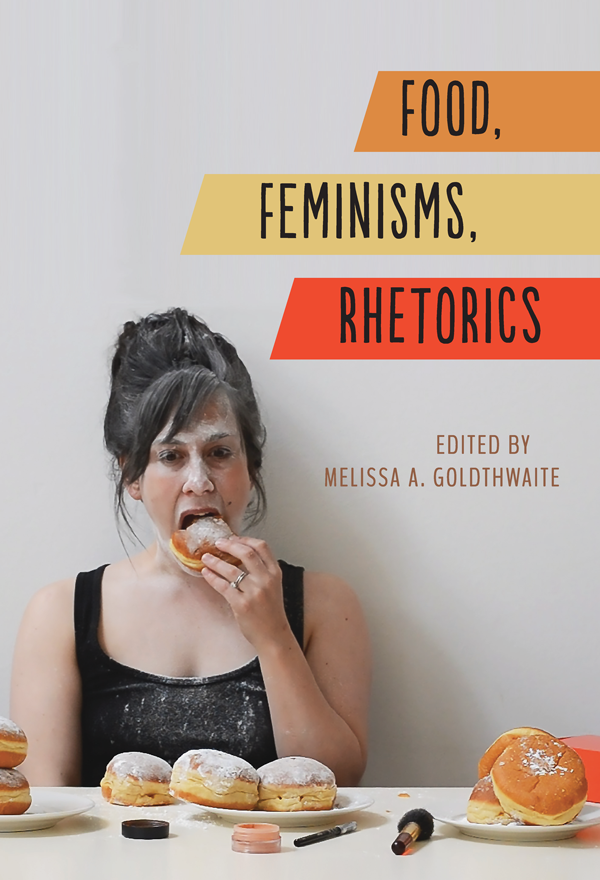

Many others contributed, too: Cheryl, again, and Shirley Wilson Logan, the editors of the Studies in Rhetorics and Feminisms series, provided support and helpful suggestions. Kristine Priddy and Judy Verdich, at Southern Illinois University Press, guided this project with attention to detail. The outside reviewers comments led to important additions and revisions. Mary Goldthwaite-Gagne introduced me to Rachelle Beaudoins art. An image from Rachelles performance piece Women Are Like That appears on the cover; if you go to her website, you can view the full performance. In addition, a sabbatical granted by Saint Josephs University gave me time to focus.

At home, two beings nourished me. I spent much of my adult life wanting to be alone in my kitchen. Even when I cooked for loved ones or guests, I didnt want help. I didnt desire conversation or collaboration while I cooked. With Howard Dinin, that changedI changed. Now, we share kitchens. Ours. For the first time in my adult life, someone else does the majority of the food shopping and cooking, freeing me to spend more time on my work.Additionally, Howard helps with that work, preparing images and offering assistance and ideas. And then theres Artemis; for nearly fourteen years, she has been my most constant and sweetest companion. When work requires long hours and deep focus, she curls up next to me and sleeps; she also gets me outside at least twice a day, and she makes sharing food a true pleasure.

To all who contributed to this project: thank you.

PREPARATION AND INGREDIENTS: AN INTRODUCTION TO FOOD, FEMINISMS, RHETORICS

Melissa A. Goldthwaite

EXAMINING FOOD-RELATED PRACTICES

A focus on food practices can help to bring specificity to examinations of cultures as well as revealing the power dynamics within them. Close attention to who is cooking what, for whom, and under what conditions can break down totalizing notions of gender, race, and class.

Arlene Avakian, Cooking Up Lives: Feminist Food Memoirs

Observe, examineso many messages ripe for interpretation. In a local department store, the spatula sold as a grill tool has a built-in bottle opener and is twice as large and sturdy as any sold near kitchen utensils. Walk the aisles of a local grocery store. Are there Hungry-Man frozen dinners, Manwiches, an entire line of Skinnygirl products? How is the store organized? Are there sections for ethnic foods, particular diets, organic foods? What foods or products are most prominent? Which ones are absent? At home, unwrap a Dove chocolate to find three words printed on the foil wrapper: chocolate loves unconditionally.

Keep looking. Look back. What foods were forbidden when you were a child? What were you fed? Where did it come from? Who prepared it? What did you refuse? What did you not know existed? What material conditions shaped your relationship to food?culture, religion, region, economics, and gender roles did you receiveand from whom?

Messages surrounding foodits availability, its preparation, its consumption, its role in the lives of individuals, families, and culturesare multiple and conflicting. Food is sustenance and poison, fuel and temptation, home culture and one of the most memorable introductions to new cultures and places. Preparing food is drudgery and joy, duty and delight. In her introduction to Kitchen Culture in America, Sherrie A. Inness writes that eating is an activity that always has cultural reverberations. Food is never a simple matter of sustenance. How we eat, what we eat, and who prepares and serves our meals are all issues that shape society (5). Such shaping messages come not just from food marketers, advertisers, and designers but from a range of sourcesmundane and literary, ethnic and economic (family practices, cultural taboos, where one lives, what one watches and reads).

With reflection and analysis, understanding of such messages can shift and change and be critiqued. In the essay Boiled Chicken Feet and Hundred-Year-Old Eggs: Poor Chinese Feasting, for example, Shirley Geok-lin Lim writes that in her family, chicken feet were only to be enjoyed by married women. Lims aunts warned that if she ate them before she was married, shed grow up to run away from her husband (217), a poignant warning since her mother had left. She further explains, The chickens were divided according to gender, the father receiving the white breast meat, the sons the dark drumsticks, and the daughters the skinny backs, while the women ate the feet and wings (218). In the first section of her essay, she critiques the gendered taboos of her childhood in Malaysia, yet as she continues, Lim considers other factors that helped create such taboos. She reflects on poverty, class differences, and the distinctions between American and Chinese cultures.

When she and her brother share soy-boiled chicken feet as adults later in the essay, Lims nuanced understanding of the complex social and economic forces that have shaped her comes through clearly. She writes that even after decades of American fast foods and the rich diet of the middle class, my deprived childhood had indelibly fixed as gastronomic fantasies those dishes impoverished Chinese had produced out of the paltry ingredients they could afford (224). Instead of earlier images of chickens feet that had stepped on duck and dog and their own shit (217), Lim gives readers a transformed understanding of this food both withheld from her and rejected by her in childhood. She provides a context for the gendered taboos and ends with the image of her brother sharing the best of [their] childhood together (224).She then presents readers with a recipe for soy-boiled chicken feet, a dish thatfor Limrepresents complex and conflicting messages.