Jeremy D. Coltman - Sorcery in Mesoamerica

Here you can read online Jeremy D. Coltman - Sorcery in Mesoamerica full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Chicago Distribution Center (CDC Presses), genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

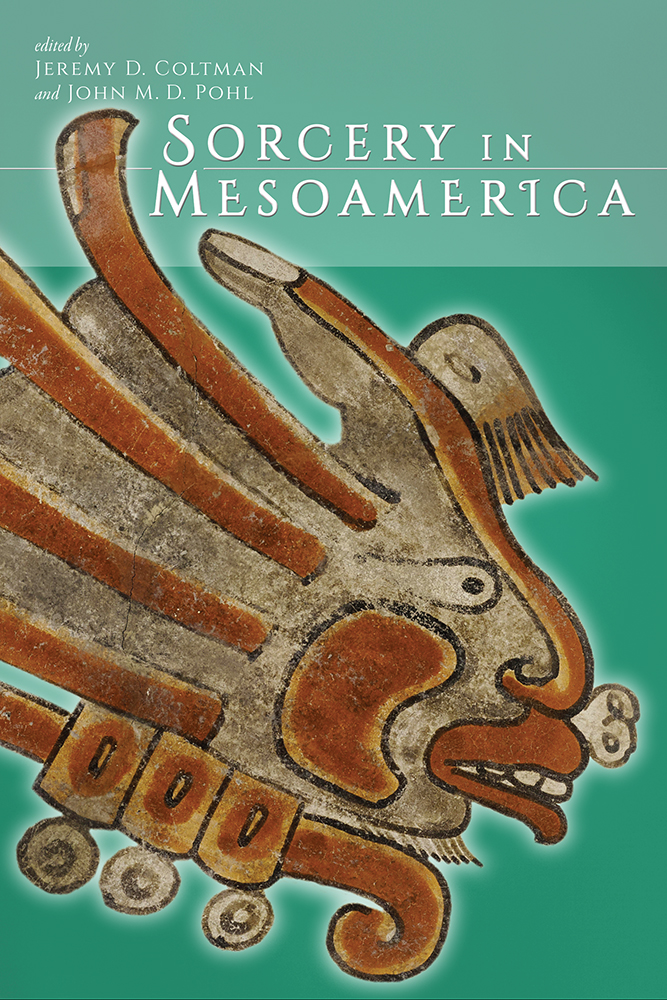

- Book:Sorcery in Mesoamerica

- Author:

- Publisher:Chicago Distribution Center (CDC Presses)

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sorcery in Mesoamerica: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Sorcery in Mesoamerica" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Sorcery in Mesoamerica — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Sorcery in Mesoamerica" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Edited by

Jeremy D. Coltman and John M.D. Pohl

U NIVERSITY P RESS OF C OLORADO

Louisville

2021 by University Press of Colorado

Published by University Press of Colorado

245 Century Circle, Suite 202

Louisville, Colorado 80027

All rights reserved

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, University of Wyoming, Utah State University, and Western Colorado University.

ISBN: 978-1-60732-944-2 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-1-60732-945-9 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-60732-954-1 (ebook)

https://doi.org/10.5876/9781607329541

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Coltman, Jeremy D., editor. | Pohl, John M. D., editor.

Title: Sorcery in Mesoamerica / edited by Jeremy D. Coltman and John M. D. Pohl.

Description: Louisville : University Press of Colorado, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020001814 (print) | LCCN 2020001815 (ebook) | ISBN 9781607329442 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607329459 (paperback) | ISBN 9781607329541 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: WitchcraftMexico. | WitchcraftCentral America. | MayasSocial life and customs. | Indians of MexicoSocial life and customs. | Indians of Central AmericaSocial life and customs.

Classification: LCC BF1584.M6 S67 2020 (print) | LCC BF1584.M6 (ebook) | DDC 133.4/30972dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020001814

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020001815

Cover illustration: Polychrome plate with glyphic sign composed of a hand with human face. Cholula, Puebla. AD 9501050. Princeton University Art Museum, y1967-147.

John M.D. Pohl and Jeremy D. Coltman

John Monaghan

Alan R. Sandstrom and Pamela Effrein Sandstrom

Lilin Gonzlez Chvez

John F. Chuchiak IV

Timothy J. Knab

David Stuart

Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos

Jesper Nielsen

John M.D. Pohl

Jeremy D. Coltman

Cecelia F. Klein

Roberto Martnez Gonzlez

Jeremy D. Coltman and John M.D. Pohl

This volume is the outgrowth of a session organized by the editors for the seventy-seventh annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology in Memphis, Tennessee. The contributors share a fascination with a number of puzzling questions about Mesoamerican supernatural belief, ritualism, and social behavior that extend from the second millennium BC to the earliest encounters with Europeans and continue to the present day. Considering the size of our endeavor, we felt that a coherent introduction would be absolutely essential to how the book is received by our colleagues. It might seem logical to simply list the papers according to regions and compose an introduction that inventories each articles highlights, except we found that this just results in a grab bag of assorted topics loosely connected by a general theme. The problem with a chronological approach, on the other hand, is that it tends to reify the image of pre-Columbian sorcery as being something exotic and mysterious, if not bizarre, as it is primarily conveyed to us through pre-Columbian art and writing. It subsequently appears to be associated with failed millenarian movements and some nasty idolatry trials in the Colonial period and then continues on as what is still widely perceived to be the corrupted and vestigial religious practices in remote rural areas of what had once been magnificent state-level religions. We now know this was not the case.

We have organized this book by putting all of our ethnographic and colonial articles together at the very beginning because we realize that each work asks very different questions about what exactly sorcery is or isnt in Mesoamerica. They discuss the pros and cons of the vocabulary of sorcery, and they demonstrate together just exactly how a holistic system and world view rooted in sorcery was transformed into what was perceived to be the positive behavioral logic in Christian belief versus the negative associated with the Devil and yet with the two continuing to vigorously coexist side by side today. In doing this we can rationalize the seeming inconsistencies in points of view and establish a basis for reconstructing an original indigenous logic behind sorcery as we then examine chronologically its various manifestations through Classic Maya city-states to the Late Postclassic Aztec Empire. In this way we avoid the customary comparative approaches of Evans-Pritchard, Turner, and others as our sources for explanatory models and analyze sorcery on the merits of our own data. The result is a profound appreciation for the evolution of cultural beliefs and avoids the pitfalls of evaluating behavior on a purely subjective basis at any particular time and place. Our goal has been therefore to create a book in which the articles mutually augment one another in such a way as to answer some major questions and provide some significant new insights into a topic that has suffered from a considerable amount of misunderstanding in the past in ways that no individual article addresses alone.

In planning this volume all the contributors expressed concern over the terminology that should be applied to the subject of sorcery, with the terms sorcerer as opposed to witch being a thorny topic as they have been used more or less interchangeably in Mesoamerica (Madsen and Madsen 1969). With his pioneering work Witchcraft, Oracles, and Magic among the Azande, E. Evans-Pritchard originally observed that the Azande of north-central Africa clearly distinguish between sorcerers and witches, the primary difference being that the sorcerer uses the technique of magic and derives his power from medicines, while the witch acts without rites and spells and uses hereditary psycho-physical powers to attain his ends (Evans-Pritchard 1937: 387). Mesoamerican ethnographers later proposed comparable distinctions between sorcerers and witches, but they also concluded that the criterion for classification is seldom absolute, and in composing this volume we were continually reminded of Victor Turners proposal: Witch beliefs can no longerif they ever couldbe usefully grouped into two contrasting categories, witchcraft (in its narrow sense) and sorcery (Turner 1964: 318; see also Nutini and Roberts 1993: 127129; Knab 1995, 2004).

There was further concern among the contributors that terms like sorcery and witchcraft represent very general categories that may mask indigenous titles for practitioners and therefore misrepresent their roles by lumping them into any single broadly defined term. There is a myriad of occupational titles for magico-religious specialists in Mesoamerica, and we would not dare suggest that one term such as witch or sorcerer would be adequate to cover them all (Lpez Austin 1988, 1: 362; Knab 2004; Pohl 2007). However, these terms as well as many others in the anthropological literature like shamanism are broadly used for comparative purposes by the contributors as they continue to provide a framework for the identification and exploration of behavioral similarities and differences and fosters communication across regional or subdisciplinary boundaries (Hill 2002: 407). Since there is no commonly accepted definition, we use indigenous terms when necessary, but many of these will continue to fall into a category of either sorcery or witchcraft, especially when dealing with actions of mal intent. In short, we seek a more refined and nuanced terminology but not at the expense of general public understanding (Klein et al. 2002: 400). Consequently, the editors have made no attempt to make the contributors adhere to any specific terminology but rather have encouraged the authors to use terms in a manner that best articulates their point of view.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Sorcery in Mesoamerica»

Look at similar books to Sorcery in Mesoamerica. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Sorcery in Mesoamerica and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.