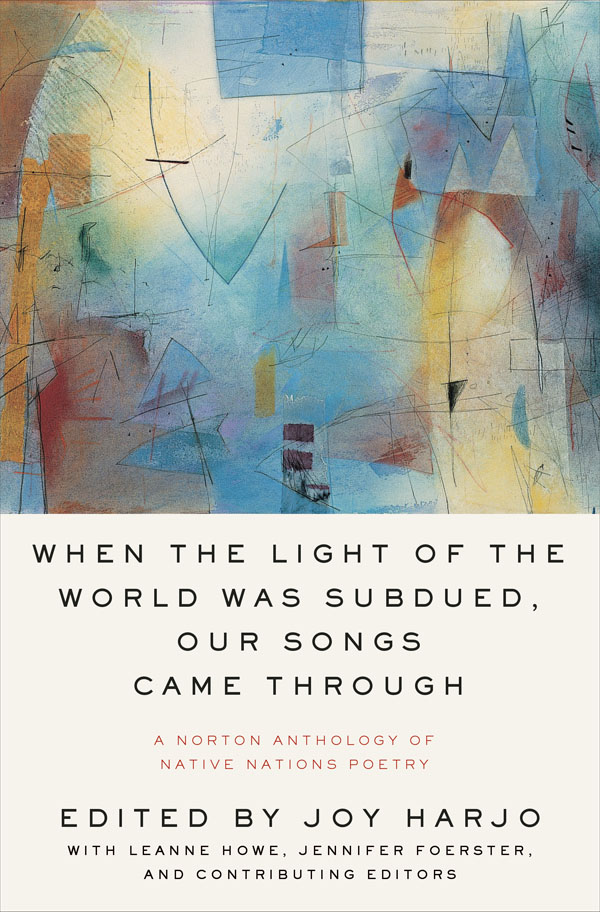

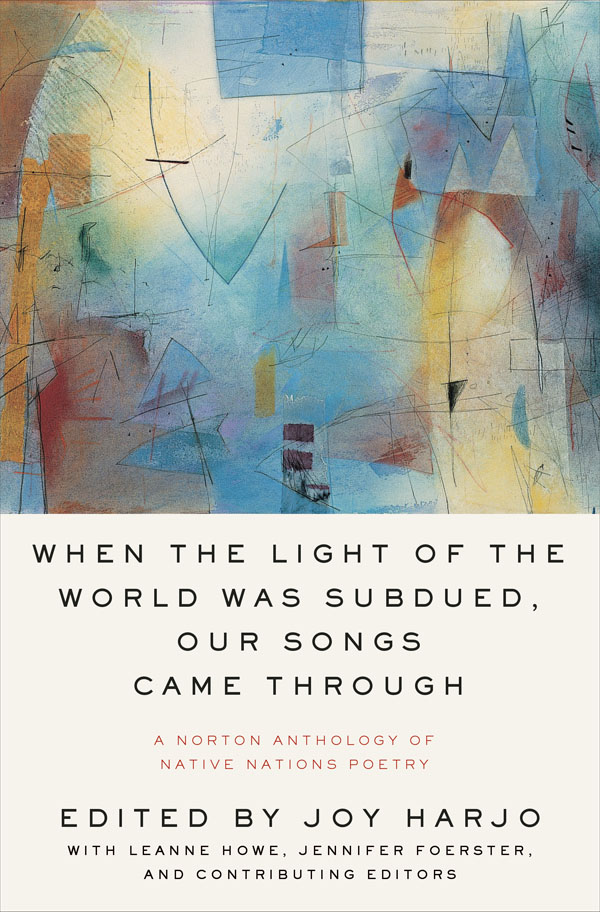

WHEN THE

LIGHT OF THE WORLD

WAS SUBDUED,

OUR SONGS CAME THROUGH

A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry

EDITORS Joy Harjo Executive Editor LeAnne Howe Executive Associate Editor Jennifer Elise Foerster Associate Editor

T HIS ANTHOLOGY is a most welcome addition to American literature. The Native Americans have always been deeply invested in language. The songs, spells, and prayers of the Native oral tradition are among the worlds richest examples of verbal art. The present collection is a comprehensive celebration of that tradition and that art. Prayer for Words My voice restore for me. Din Here is the wind bending the reeds westward, The patchwork of morning on gray moraine: Had I words I could tell of origin, Of Gods hands bloody with birth at first light, Of my thin squeals in the heat of his breath, Of the taste of being, the bitterness, And scents of camas root and chokecherries.

And, God, if my mute heart expresses me, I am the rolling thunder and the bursts Of torrents upon rock, the whispering Of old leaves, the silence of deep canyons. I am the rattle of mortality. I could tell of the splintered sun. I could Articulate the night sky, had I words. N. S COTT M OMADAY

CONTENTS

1800s // Choctaw WHEN THE

LIGHT OF THE WORLD

WAS SUBDUED,

OUR SONGS CAME THROUGH

W E BEGIN WITH THE LAND .

We emerge from the earth of our mother, and our bodies will be returned to earth. We are the land. We cannot own it, no matter any proclamation by paper state. We are literally the land, a planet. Our spirits inhabit this place. We are not the only ones.

We are creators of this place with each other. We mark our existence with our creations. It is poetry that holds the songs of becoming, of change, of dreaming, and it is poetry we turn to when we travel those places of transformation, like birth, coming of age, marriage, accomplishments, and death. We sing our children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren: our human experience in time, into and through existence. The anthology then is a way to pass on the poetry that has emerged from rich traditions of the very diverse cultures of indigenous peoples from these indigenous lands, to share it. Most readers will have no idea that there is or was a single Native poet, let alone the number included in this anthology.

Our existence as sentient human beings in the establishment of this country was denied. Our presence is still an afterthought, and fraught with tension, because our continued presence means that the mythic storyline of the founding of this country is inaccurate. The United States is a very young country and has been in existence for only a few hundred years. Indigenous peoples have been here for thousands upon thousands of years and we are still here. When the first colonizers from the European continent stepped into our tribal territories, we were assumed illiterate because we did not communicate primarily with written languages, nor did we store our memory in books and on papers. The equating of written languages to literacy came with an oppositional world view, a belief set in place as a tool for genocide.

Yet our indigenous nations prized and continue to value the word . The ability to speak in metaphor, to bring people together, to set them free in imagination, to train and to teach, was and is considered valuable, more useful than gold, oil, or anything else the newcomers craved. Many of our known texts, though preserved in orality, stand next to the top world literary texts, oral or written. The Din Blessingway Chant, or Hzhn, is a poetic song text that is remembered word for word and is central to a ceremony for setting a community in the direction of beauty, or healing. The Pele and Hiiaka saga of two sisters is an epic poem that carries profound cultural significance to this day in the practice and fresh creation of lelo Hawaii. Like the Mahabharata of the Hindu religion or the Iliad of ancient Greece, every culture, every tradition has its literature that guides and defines itand the cultures indigenous to North America are no different.

What then distinguishes indigenous poetry from other world poetry traditions? Much depends on indigenous language constructs, which find their way into poems written in other languages, as in English here. My own poem She Had Some Horses would not have been written without stomp dance, or without my having heard Navajo horse songs. So many poetry techniques are available, whether its utilizing metaphor, syntactic patterning, or some other application of poetic tools; and those of us who read and listen to poetry want our ears and perception bent for unique insight and want to see how the impossible becomes momentarily possible in the arrangement of language and meaning. This is true of poetry in all languages. Each tribal entity and language group is different. English then has become a very useful trade language.

We use it to speak across tribal nations, to people all over the world. Many of the poets here find a way to carry out established tribal form and content in English. Consider Louis Little Coon Olivers The Sharp-Breasted Snake poem and its movement on the page. Some of the poets dont want that at all, and instead they create and work within generational urban cultural aesthetics. What is shared with all tribal nations in North America is the knowledge that the earth is a living being, and a belief in the power of language to create, to transform, and to establish change. Words are living beings.

Poetry in all its forms, including songs, oratory, and ceremony, both secular and sacred, is a useful tool for the community. Though it is performative there is no separation of audience and performer. Even as we continue to create and perform our traditional forms of poetry, we have lost many of these canonical oral texts due to destruction throughout the Western Hemisphere of the indigenous literary field by the loss of our indigenous languages. We were forced to forsake our languages for English in the civilizing genocidal process. We are aware of the irony, for many of us, of our writing in English. But we also believe English can be another avenue through which to create poetry, and poetry in English and other languages can live alongside texts created and performed within our respective indigenous languages.

It is the nature of the divided world in which we live. Many who open the doors of this text arrive here with only stereotypes of indigenous peoples that keep indigenous peoples bound to a story in which none of us ever made it out alive. In that story we cannot be erudite poets, scholars, and innovative creative artists. It is the intent of the editors to challenge this: for you to open the door to each poem and hear a unique human voice speaking to you beyond, within, and alongside time. This collection represents the many voices of our peoples, voices that range through time, across many lands and waters. May all readers of this anthology bear a new respect for the unique contributions of these poets of our indigenous nations.

We are more than 573 federally recognized indigenous tribal nations in the mainland United States; 231 are located in Alaska alone. That number doesnt include the indigenous peoples of Hawaii, the Kanaka Maoli, whose nation numbers over 500,000, and the indigenous peoples of Guhan and Amerika Smoa. We speak more than 150 indigenous languages. At contact with European invaders we were estimated at over 112 million. By 1650 we were fewer than six million. Today we are one-half of one percent of the total population of the United States.

Next page

EDITORS Joy Harjo Executive Editor LeAnne Howe Executive Associate Editor Jennifer Elise Foerster Associate Editor

EDITORS Joy Harjo Executive Editor LeAnne Howe Executive Associate Editor Jennifer Elise Foerster Associate Editor  T HIS ANTHOLOGY is a most welcome addition to American literature. The Native Americans have always been deeply invested in language. The songs, spells, and prayers of the Native oral tradition are among the worlds richest examples of verbal art. The present collection is a comprehensive celebration of that tradition and that art. Prayer for Words My voice restore for me. Din Here is the wind bending the reeds westward, The patchwork of morning on gray moraine: Had I words I could tell of origin, Of Gods hands bloody with birth at first light, Of my thin squeals in the heat of his breath, Of the taste of being, the bitterness, And scents of camas root and chokecherries.

T HIS ANTHOLOGY is a most welcome addition to American literature. The Native Americans have always been deeply invested in language. The songs, spells, and prayers of the Native oral tradition are among the worlds richest examples of verbal art. The present collection is a comprehensive celebration of that tradition and that art. Prayer for Words My voice restore for me. Din Here is the wind bending the reeds westward, The patchwork of morning on gray moraine: Had I words I could tell of origin, Of Gods hands bloody with birth at first light, Of my thin squeals in the heat of his breath, Of the taste of being, the bitterness, And scents of camas root and chokecherries.  1800s // Choctaw WHEN THE

1800s // Choctaw WHEN THE