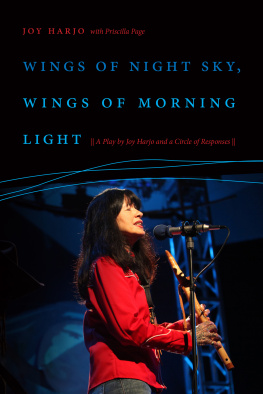

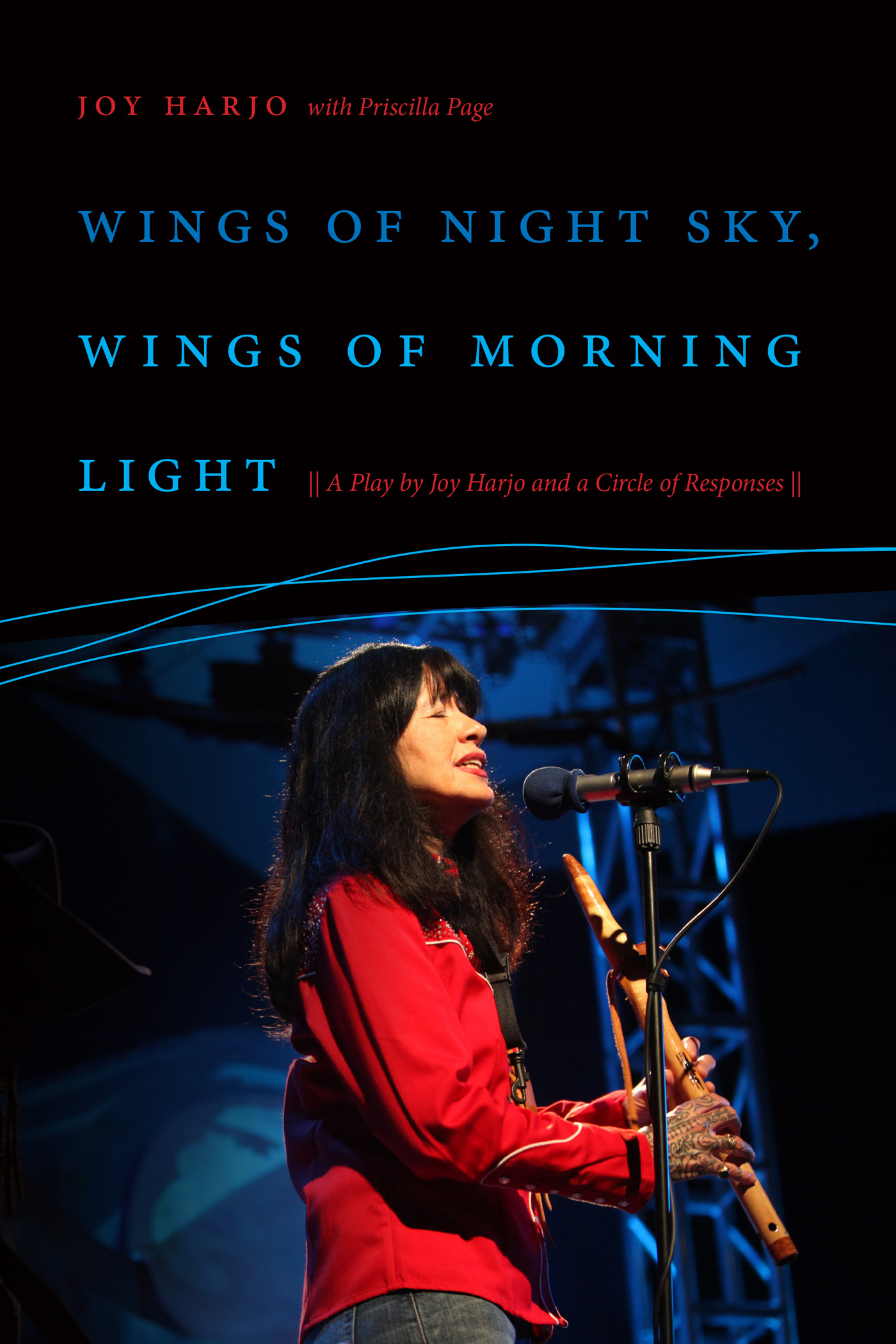

WINGS OF NIGHT SKY || WINGS OF MORNING LIGHT

Joy Harjo with Priscilla Page

WINGS OF NIGHT SKY, WINGS OF MORNING LIGHT

|| A Play by Joy Harjo and a Circle of Responses ||

Wesleyan University Press Middletown, Connecticut

Wesleyan University Press

Middletown CT 06459

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress

2019 Joy Harjo and Priscilla Page

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed by Mindy Basinger Hill

Typeset in Minion Pro

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication

Data available upon request

Hardcover ISBN: 978-0-8195-7865-5

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-8195-7866-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-0-8195-7867-9

5 4 3 2 1

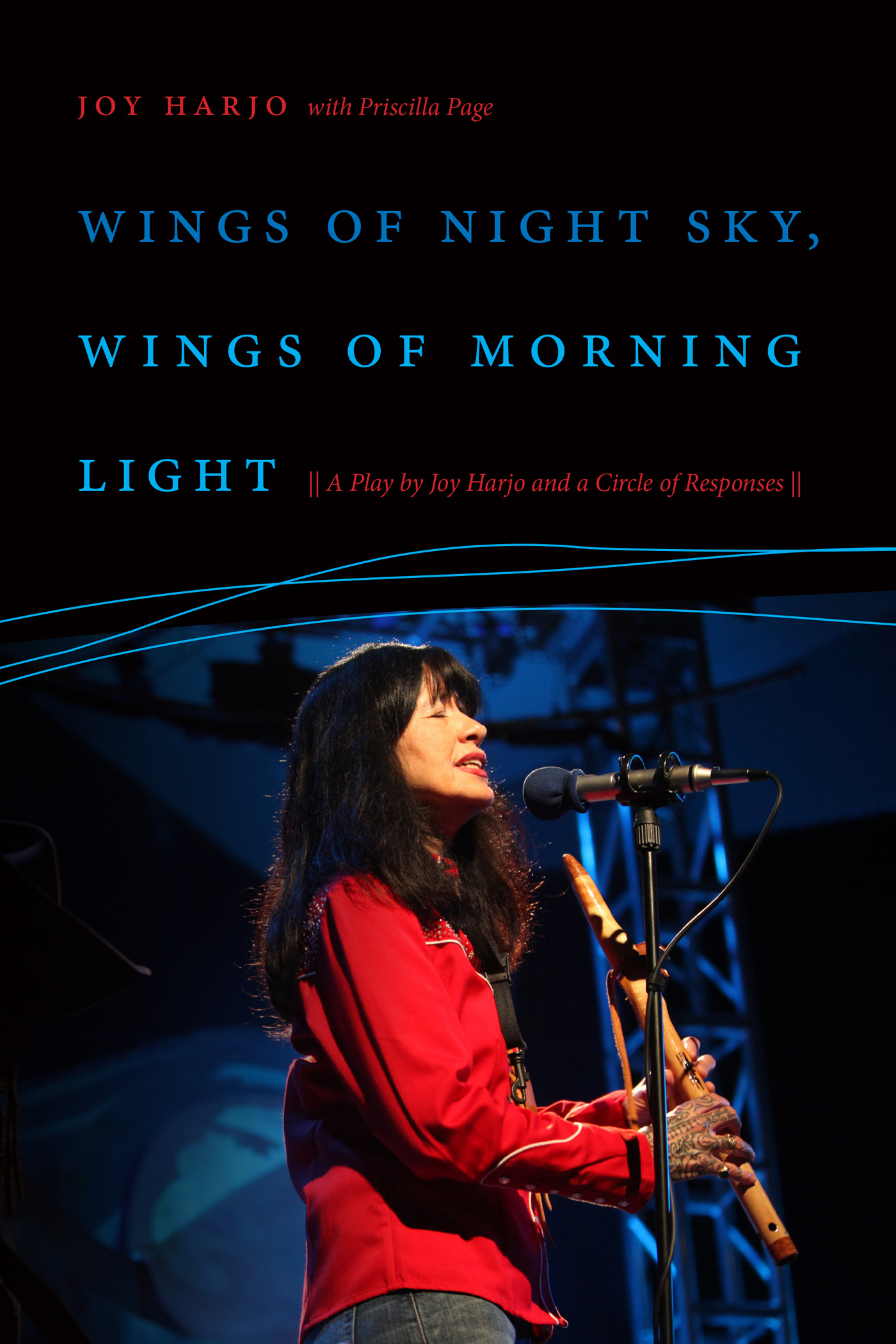

Cover photo of Joy Harjo playing the flute Anton Dontscheff / Silvia Mautner Photography.

CONTENTS

MARY KATHRYN NAGLE ||

JOY HARJO ||

PRISCILLA PAGE ||

PRISCILLA PAGE ||

PRISCILLA PAGE ||

PRISCILLA PAGE ||

WINGS OF NIGHT SKY || WINGS OF MORNING LIGHT

MARY KATHRYN NAGLE

Joy Harjos Wings || A Revolution on the American Stage

In my familys blue-sky memory, we loved my father without question. We loved his laugh, his stories, his swinging us through the sky. We struggled with his fight, his jab, and his fear. When I looked through my dreaming eyes, he was still a boy of four standing by his mothers casket. She was his beloved grandfathers great-great-granddaughter. She liked to paint, blew saxophone in Indian territory and traveled about on Indian oil money. Still, grief from history grew in her lungs. She was dead of tuberculosis by her twenties. The grief had to go somewhere. We had no one left in our family who knew how to bury it. So it climbed onto her little boys back.

Joy Harjo, Wings of Night Sky, Wings of Morning Light

For too long our grief has had nowhere to go. So we carry it in our lungs. We bury it in our kidneys. It cakes our hearts. We deposit it onto the backs of our children, and our childrens children.

We know our stories are medicine. We know they bring about healing. But we have not been permitted to share them. At this point in history, the American stage has, for the most part, silenced the voice of Native artists.

Wings of Night Sky, Wings of Morning Light is exceptional. It is an extraordinary work of extraordinary magnitude for several reasons, but one of its most unique, rare attributes is that it has been presented on a professional American stage. Wings constitutes one of but a small handful of Native plays to have ever been presented on such a stage. For me and the other Native playwrights in my generation, Wings stands as a source of inspiration. The impossible is possible. And now, with the publication of Wings, my hope and prayer is that Americans will come to see that our stories truly are worth reading and staging, and thus for our Native writers, worth writing.

For the generations and generations of American Indians who have never heard or seen a performance by a Native woman on a professional American stage, Joy Harjos Wings of Night Sky, Wings of Morning Light offers a powerful healing. Harjos heroine Redbird takes her audience on a journey through generations of trauma and survival in a musical revelry that celebrates American Indian resistance. For those of us still attempting to make sense of the trauma lodged in our hearts, Wings creates a release valve. Through ceremony, song, and kinship, a public space is created where healing can collectively take place and grief can be processed.

For the generations and generations of non-Natives who have been taught that American Indians are nothing more than the image on the back of a Washington, DC, football jersey, Wings commands a powerful reckoning. Wings introduces non-Native audience members to what will be, for many, their first interaction with an actual Native person.

Redbirds journey is breathtakingly personal. Of course, when it comes to putting Indians on the American stage, the personal is political. Today, statistics reveal that Americans who go to the theater are more likely to witness the performance of redface onstage than the performance of Native stories by Native people. As a Muscogee Creek woman created by a Muscogee Creek playwright, Redbird is everything her contemporary redface counterparts in Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, An Octaroon, and the Wooster Groups Cry, Trojans! (to name a few) are not. Instead of a costume, a drunk Indian who only grunts onstage, a joke, or a stereotype, Redbird is an articulate Native woman with something intelligentindeed profoundto say about the attempted destruction of her people and sovereign Tribal Government.

We need to see more Redbirds on the American stage. I lived and wrote plays in New York for five years. I found the entire experience rather depressing. During my five years in New York, I witnessed numerous performances of redface on many of New Yorks most prestigious stages. Not oncein all of my five yearsdid I ever see a non-Native professional theater company produce a full-length play by a Native playwright. Indeed, I arrived three years after the Public Theater workshopped Harjos Wings, but they never fully produced it. I am encouraged that this publication of Wings will allow other theaters to now follow the artistic lead of Randy Reinholz and Jean Bruce Scott, co-creators of Native Voices at the Autry, who premiered the work in 2009 in Los Angeles. This is an important play that openly raises consciousness and exposes truths. I know we are ready for more productions.

To be clear, the absence of authentic Native representation on the America stage is no accident. Redface was purposefully created to tell a false, demeaning story. Redface constitutes a false portrayal of Native peoplemost often performed by non-Natives wearing a stereotypical native costume that bears no relation to actual Native people, our stories, our struggles, or our survival in a country that has attempted to eradicate us. The continued dominant perception that American Indians are the racial stereotypes they see performed on the American stage is devastating to our sovereign right to define our own identity. Of course, thats why it was invented.

In the 185 years since Andrew Jackson drafted and signed into law his Indian Removal Act, portrayals of Native Americans in the American theater have changed very little. The redface performances that originated at the time of removal continue to dominate the American stage today, but for the first time, now, we have the opportunity to change the narrative. We have the opportunity to replace a false representation with a real one.

In this respect, Harjos placement of an articulate, brilliant, and musical Native woman front and center on the American stage constitutes nothing less than an act of revolution. Wings is a magnificent rebellion. Redbirds narrative demonstrates defiance.

In contrast to the majority of contemporary Native representations onstage, the Native protagonist in Wings does not grunt incoherent sounds, nor does she portray the loss of her Muscogee ancestral homelands as a joke in a modern day rock musical. Instead, the reality of the Trail of Tears is introduced as a shared communal experience of survival, an experience that continues to shape the journey and identity of Muscogee Creek Nation citizens today. Harjo writes,

CEHOTOSAKVTES CHENAORAKVTES MOMIS KOMET AWATCHKEN OHAPEYAKARES HVLWEN

Two beloved women sang this song on the trail of tears. One walked near the front of the people, one near the back. When either began to falter, they would sing the song to hold each other up.

Next page