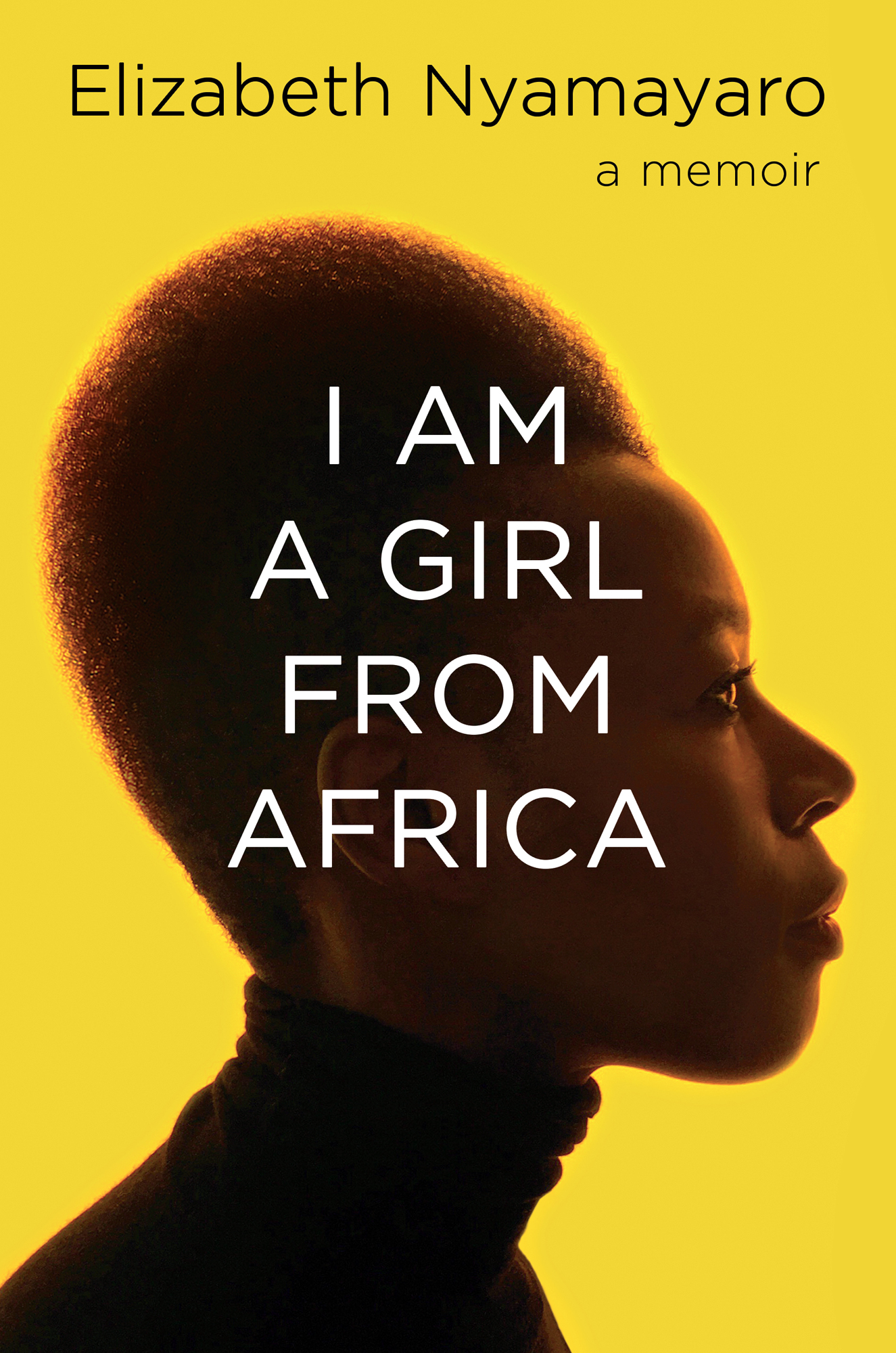

Elizabeth Nyamayaro - I Am a Girl from Africa

Here you can read online Elizabeth Nyamayaro - I Am a Girl from Africa full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Scribner, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:I Am a Girl from Africa

- Author:

- Publisher:Scribner

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

I Am a Girl from Africa: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "I Am a Girl from Africa" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

I Am a Girl from Africa — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "I Am a Girl from Africa" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Elizabeth Nyamayaro

A Memoir

I Am a Girl from Africa

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

For my dearest Gogo, whose indomitable spirit, love, and wisdom formed the core of who I am.

To my beloved continent, this is my love letter to you. I cannot imagine any greater gift than being a child of the African soil.

You cannot tell a hungry child that you gave them food yesterday.

Zimbabwean proverb

Deep in the African wilderness, rolling hills open onto a barren maize field. In the middle of that field stands a huge, useless tree. I lie underneath that useless tree unable to move. I am eight years old. I am all alone.

Stand, I tell myself, but I cannot. I lie on my stomach, my legs stretched out, my arms limp at my sides, my palms turned toward the heavens, begging for mercy. I burrow my face deeper into the ground, seeking shelter from the scorching sun, yet the earth feels as hot as fire, practically sizzling beneath me. There is no cool or comfortable place to hide. The leaves of the tree are long gone, and with it the shade, burned away by the punishing drought that has descended on our small village in Zimbabwe.

Rise, I think, but I cannot. I am simply too weak to move. I am starving. I have had nothing to drink or eat for three days. My shrinking stomach growls like two hungry hyenas fighting over a goat. I am so thirsty its as if tiny, sharp razors slice the inside of my throat with each breath or attempt to swallow. I have never felt so hollow and wasted from hunger. I worry that the drought may never end, and I will never leave this tree. I will die here, I think, but I am too tired to be truly frightened.

My world has changed from one of abundance and joy to one of fear and emptiness. It seems a long time ago that I cooked sadza (maize meal) with goat stew alongside my gogo (grandmother), whom I live with inside our round, grass-thatched hut that is small-small, but big enough for the two of us to cook and eat and sleep and pray. Our warm, cozy hut, just like all the other huts in our small village of Goromonzi, stands at the top of a hill surrounded by cow pastures and farmland. Goromonzi is the only home I have ever known, but through the haze of hunger I struggle to remember the faces and voices of my village: Gogos three sons and all her other relatives, who are my ambuyas (aunts) and sekurus (uncles), and their children, whom I call sisis (sisters) and hanzwadzis (brothers).

Long before the drought, all of us gathered in Gogos yard on special days, eating and laughing and feasting. Each family brought baskets full of food picked from our fields at the bottom of the hill and the gardens tucked behind our round huts: fresh maize, sweet potatoes, watermelons, groundnuts, pumpkins, mangoes, and guavas. The sekurus slaughtered a cow gifted by one of the families, providing plenty-plenty cow stew, which we washed down with soured milk from our stubborn goats until our bellies rejoiced and our hearts felt satisfied. We wanted for nothing because the food belonged to everyone; we shared it all, bartering and trading with each other for things we didnt grow. Gogo traded her large orange pumpkins, which tasted almost as sweet as honey, for small packets of black-eyed beans and groundnuts from the ambuyas. If you needed anything, you only had to ask, and often somebody offered what they knew you needed before you did. After supper, on our feast days, we sat around a huge fire under the dark African sky perforated with tiny shiny stars, singing songs of praise to God, calling for the rain to return.

God always answered our prayers, and each year the rain returned, filling our days with purpose. Ox-drawn plows worked the fields; wooden and metal hoes tilled the land; family stood by family, helping to tend the crops until they sprouted from the ground. Our fields were lush and green; our harvest was bountiful. Gogo and the sekurus sold our maize, sunflower seeds, and other crops at the Township Center in the next village, to buy any food we couldnt grow ourselves. We found meaning in our work, making sure that we all did our part to take care of our families and of each other. It was a happy life.

That was then, and this is now. For two years, God has refused to answer our prayers. He has left us with Satans punishing heat, which is killing everything in its path. He has left us with only the little food from the previous harvest, which is not enough. Even though we share whatever we can, even though we count our maize and beans each day before cooking, even though we skip meals, ignoring our hunger pangs, the little food we have left is slowly running out.

At first, when the rain failed to come, Gogo spoke directly to God. I will not stop until you bring back the rain. I will not rest. Do you hear me, God? Her prayers went unanswered, but she refused to give up. Gogo gathered all the ambuyas and sekurus, and together we all prayed for rain againthis time without the feastas our food began to diminish. We prayed for so many days and nights and so loudly and faithfully that our knees were bruised and our voices were hoarse. Still, God did not respond. Now I wonder if the world is ending, but this thought moves slowly through my mind, as if through mud.

When Gogo left the village a few days ago, she told me, An illness has visited a sekuru from the mujuru village, which is far from our village. Sunlight fell across the hut, casting light across the walls and floor. Gogo wrapped her few belongings in a faded brown cloth: a pair of underwear; two maroon dresses, both with tiny holes from termites; a half-used jar of Vaseline; and, of course, her Bible.

I can help, I said, offering to carry Gogos Bible as I always do on Sundays when we go to church wearing our nice-nice clothes and special church hats.

No. I am going with the ambuyas and will be back soon-soon. Eat the boiled maize when you get hungry. She pointed to the black clay pot. She tapped the water container. Yes. There is enough for two days.

I nodded, Okay, lets pray. Kneeling with Gogo on the floor, I prayed for God to protect my family on their journey. I waved goodbye and watched Gogo disappear behind the guava and mango trees behind our hut, descending the hills with her belongings bundled on top of her head to join the ambuyas.

That was five days ago. The water container is empty, and the food is long gone. With no food or water for three days, I feel as though I am slipping out of my body. I manage to lift my face by pushing slowly-slowly into the dry ground with arms that feel as heavy as the thickest tree branches. I sit up, wipe the dirt from my face, and open my eyes.

The light burns my tired eyes as if Im staring at the sun. Sitting alone in Gogos devastated field, I am no longer surrounded by all things bright and beautiful, as the church hymn goes. Before me is an unrecognizable landscape, strange and scary. All that remains is scorched baby maize shoots that stood no chance against Satans punishing heat, the heat that dried up our river, leaving us with no water to drink; destroyed our crops; and killed our animals, leaving

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «I Am a Girl from Africa»

Look at similar books to I Am a Girl from Africa. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book I Am a Girl from Africa and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.