Pagebreaks of the print version

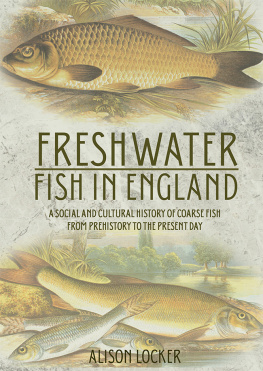

Freshwater Fish

in England

A social and cultural history of coarse fish from prehistory to the present day

Alison Locker

Published in the United Kingdom in 2018 by

OXBOW BOOKS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083

Oxbow Books and the author 2018

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78925-112-8

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78925-113-5 (epub)

Mobi ISBN: ISBN 978-1-78925-114-2 (Mobi)

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018956017

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

| UNITED KINGDOM | UNITED STATES OF AMERICA |

| Oxbow Books | Oxbow Books |

| Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449 | Telephone (800) 791-9354, Fax (610) 853-9146 |

| Email: | Email: |

| www.oxbowbooks.com | www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow |

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate Group

Front cover: Carp (top) and barbel with two gudgeon. From Rev. William Houghton (headmaster, naturalist and angler 18281895). 1879. British Freshwater Fishes. Webb & Bower Facsimile edition 1981.

Back cover: Perch. From Eleazar Albin (naturalist, artist and engraver 16901742) 1794. The History of Esculent Fish. London. www.biodiversitylibrary.org .

D EDICATION

For Gerald, with thanks, who now knows more about fish than he might have ever wished.

List of plates

Plate 1. Archaeological fish sample from a sieved deposit

Plate 2. Dentary and examples of vertebrae from reference fish

Plate 3. Cyprinid pharyngeal bones from reference fish

Plate 4. Bishops Waltham ponds. Hampshire

Plate 5. Old Alresford pond. Hampshire

Plate 6. a) Demi luce rising out a ducal coronet. Part of the heraldic device of the Gascoigne family of Gawthorpe; b) two barbels respecting each other, conjoined by collars and chain pendant. Heraldic device of the Colston family

Plate 7. View of Nonsuch Palace, Surrey, with fish sellers shown in the panel below

Plate 8. Chinese Goldfish

Plate 9. Frontispiece of The Experienced Angler or Angling Improved

Plate 10. Angling. Wenceslas Hollar (16201670)

Plate 11. a) Azurine, dobule and rudd; b) Graining and dace

Plate 12. a) Carp; b) Pike

Plate 13. Live Baiting for Jack. R. G. Reeve from a painting by James Pollard (17921867)

Plate 14. The Goldfish Seller George Dunlop (18351921)

Plate 15. a) Flies; b) perch fry and Messenger frog bait for pike

Plate 16. Poppleton lakes, Yorkshire

Pre-decimalisation currency (obsolete from 1971)

One pound () = 20 shillings (s) or 240 pence (d)

One guinea = 21 shillings

One shilling = 12 pence

One halfpenny = pence

One farthing = pence

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Martyn Allen, Rob Britton, Gordon Copp, Sheila Hamilton Dyer, Richard Hoffmann, Martin Locker, David Neal, Rebecca Nicholson, Rebecca Reynolds, Dale Serjeantson, Ingvar Svanberg, Graham Turner, Lorenzo Vizilli and the Fulling Mill.

Foreword

This book grew out of a paper on the social history of coarse angling in England from 17501950 (Locker 2014a). The time scale was a small part of a much bigger story of how we have viewed and used coarse fish; in essence obligate freshwater species usually caught by bait not fly. I have deliberately not included a lot of statistical data and tried with varying degrees of success to avoid making it a testament to my unpublished site reports, of which all zoo-archaeologists have far too many. I hope it will appeal to a range of fish enthusiasts. Lots of people in different fields have helped me, perhaps unwittingly, but the mistakes are all mine.

Introduction

Some history, biology, archaeology and science

Animal histories, by default, are told from a human perspective, which often says more about our sensibilities and culture than the animals themselves (Fudge 2002). From the natural distribution of freshwater fishes after the last Ice Age, colonising England through rivers in the land bridge from Europe, their story has been shaped by human intervention through introductions, manipulation and pollution of waterways, land ownership and fishing. Given the large number of waterways it may seem surprising that, from the historic period, marine fish are generally dominant in archaeological fish bone assemblages. Freshwater fishing is a far less risky enterprise and requires less investment in terms of boats and crew than sea fishing. However as an island nation with rich fishing grounds both off and inshore marine fish became increasingly more prominent through time and, from the eleventh century, dominate the fish supply. Herring (Clupea harengus), cod (Gadus morhua) and other marine shoaling fishes could be caught seasonally in very large numbers and became international business, driving the development of fishing methods to maximise the catch.

The English, despite being islanders with historically major fishing fleets, have never been known as a nation of fish eaters: fish and chips is a relatively recent tradition. The English reputation as carnivores referred especially to beef, which by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries became a sign of both nationhood and Protestantism (Rodgers 2003, 2, 94). Meat represented masculinity and strength, with no disconnect from the living animal to carcass to meat on the plate. There was no boning out to remove any hint of its origin and sanitise it, as frequently found today. Fish was often portrayed as penitential, though seldom used in penitentiaries, only morally improving. There are references to the tedium of eating fish on Catholic religious fish days, which occupied nearly half the year during the Middle Ages before the Reformation. Salted and dried cod and salted and pickled herring were most common, the intransigence of dried cod tempered by use of the stockfish hammer prior to soaking. Secular fish days restored after the Reformation in Protestant England were economically driven to save meat consumption and encourage the growth of fishing fleets, a nursery for sailors. The landed classes were to practise naval skills in scaled down models of warships for entertainment on their own lakes in the eighteenth century (Felus 2016).

Today, although fish is seen as healthy, we eat small quantities compared to meat and demand focuses on a narrow range, primarily cod, tuna (both have suffered from overfishing) and increasingly, farmed salmon. There is progress on farming cod and halibut, but at present no likelihood of producing these at competitive market prices. Fish conservation groups and chefs try to promote underused and sustainable species to relieve the pressure on over fished favourites. However, they concentrate on marine or migratory species, there is no enthusiasm to return to pike, perch or any of the carp family found in British freshwater systems. These fish are still eaten in many parts of Europe and cyprinids (the family that includes common carp) are particularly popular in Asia, farmed, in ponds and as part of a dual system in flooded rice fields. Once valuable property in the managed private freshwater pond systems of medieval Britain, the story of their demise as food and rise to prized coarse anglers quarry reflects changes in English culture.