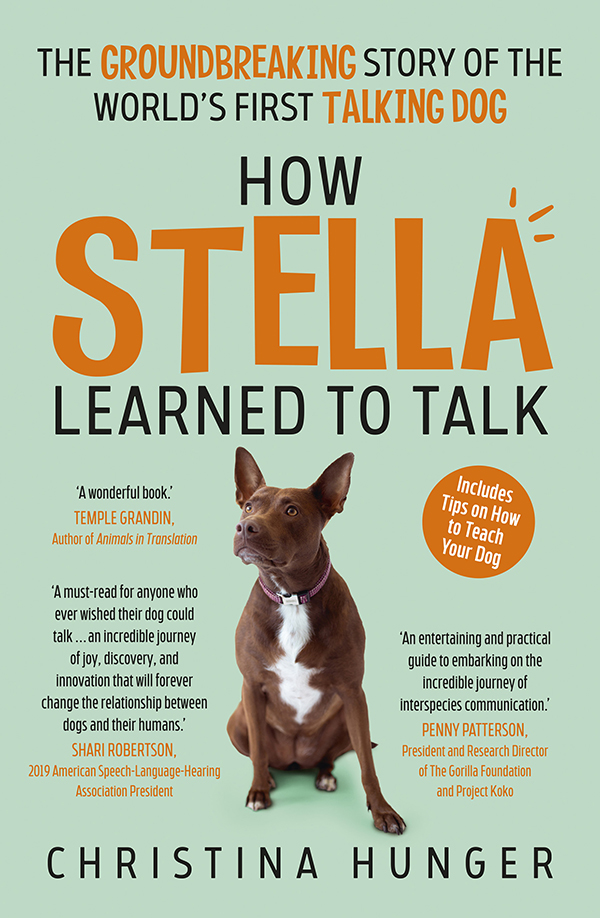

Christina Hunger - How Stella Learned to Talk

Here you can read online Christina Hunger - How Stella Learned to Talk full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Allen & Unwin, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:How Stella Learned to Talk

- Author:

- Publisher:Allen & Unwin

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

How Stella Learned to Talk: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "How Stella Learned to Talk" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

How Stella Learned to Talk — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "How Stella Learned to Talk" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

As I sat on a six-foot-wide swing resembling a giant padded block, I held my breath in anticipation. Oliver, my speech therapy client, was sitting with me holding his tablet-sized communication device. Oliver rarely initiated using his talker without my help. But today he grabbed it as soon as we met. What did he want to tell me?

Even though Oliver was only nine years old, he was almost as tall as me, his twenty-four-year-old speech-language pathologist. His basketball shorts and T-shirt made him look like any typical nine-year-old boy. But the braces on his legs, noise-reducing headphones covering his ears, and communication device strapped over his shoulder indicated that something was different. Oliver had autism spectrum disorder. He had been coming to this pediatric clinic in Omaha, Nebraska, for physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy for years.

Oliver squinted, his finger hovering over the screen. I focused on what Oliver was about to say, blocking out the noise of children swinging, climbing the rock wall, and riding on scooters around us in the gym.

Possibilities ran through my head. Maybe he would say one of the words we had been practicing on the swing for the past couple of weeks. Since Oliver learned best while he was in motion, we spent much of our sessions practicing words such as go, stop, fast, and slow while swinging. I loved modeling the word fast on Olivers device and pushing him as high as I could. Oliver would squeal and throw his head back in laughter, savoring every second of the increased speed. It was impossible for anyone to watch him without smiling. His pure joy lit up the entire room.

Oliver tapped one of the sixty icons on his tablet, which opened a new page of word choices. He traced the brightly colored rows with his index finger before pausing over a single square. When Oliver pressed it, the synthesized voice said, rice.

Rice? I paused. Oliver and I were in the middle of a gym, not a kitchen. Rice was about the last thing I expected him to say. Eat rice at lunch? I asked. After I said each word, I pushed the corresponding button on his tablet. The best way for Oliver to learn how to use his talker was to see other people using it as well.

Oliver grunted and kicked his legs in frustration. That was not what he was trying to say.

I glanced at my watch, 4:35. Maybe you want rice for dinner after therapy, I said. Want eat rice?

Oliver swatted my hand away, then repeated himself, Rice rice.

Oliver said rice in our session last week, too, but I did not really think anything of it. Since there was no rice around, I chalked it up to Oliver exploring new vocabulary. He had only had this communication device for a few months, and it can take a while before kids start using words intentionally on their own. They need time to explore words and to see and hear their communication system in use before they can be expected to talk with it. Its like how babies need to hear people using language for a whole year before they start saying words on their own. Now that I knew Oliver saying rice was not an isolated occurrence, I modeled everything I could think of that was related to rice. I used Olivers device to try a variety of phrases.

Was Oliver trying to tell me he was hungry and wanted to eat rice? Was he trying to say he liked rice? What if he hates rice and was trying to tell me it is bad? I modeled rice good, rice bad, like eat rice, all done eat rice, Oliver eat rice, school eat rice, everything I could possibly think of. Each time I tried a new phrase, I paused to assess his reaction. Oliver understood much more than he could say; his receptive language skills were significantly greater than his expressive language skills. If I said the right phrase he was trying to communicate, he would get excited. It reminded me of how I felt when trying to say a word in French years after I learned it in high school. If I read the word or heard someone say it, I would know what it meant. But it was so much harder for me to come up with the word on my own. Thats because my French receptive language skills were much higher than my French expressive language skills.

Oliver ripped his headphones off and threw them to the ground. He rattled the swing, knocking my clipboard off it while grunting.

Its okay, its okay. Were okay. You sound mad, Oliver, I said. I held the device in front of him and modeled, mad. I needed to redirect him before things got worse. The fastest way to do that was to start swinging. No matter what was going on, Oliver always loved to swing. This is true for a lot of children with autism. The rocking motion helped regulate his sensory system. Within a minute of using all my body weight to propel Oliver as high as possible, he returned to his giggly self. I fixed the situation for now so we could salvage our session but did not truly solve the problem. Why is Oliver saying rice? And why is Oliver getting so mad when I try talking about rice?

Oliver was one of the many children on my caseload learning how to use a communication device to talk. Communication devices are a form of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). AAC is a fantastic tool that gives people with severe speech delays or disorders the ability to say words through another medium. Occasionally Oliver verbally repeated single words he heard in a video or from whoever around him was speaking, but at nine years old, that was the extent of his verbal speech abilities. Many people mistakenly believe that verbal speech skills represent a persons intelligence or language abilities. One of my favorite things about being a speech-language pathologist is shattering this misconception. I love introducing AAC to children who had been misunderstood for years and watching great transformations unfold.

In graduate school, one of my clients had been using an AAC device for a couple of years. She primarily communicated in two-word phrases until the day she felt the sleeve of a fuzzy sweater I had not worn there before. She looked at me and said, New purple sweater like. I had no idea that she knew how to say the word sweater or had been paying attention to my wardrobe this whole time.

At the clinic, I recently increased another one of my clients number of visible words on his device from about twenty to the full capacity of two thousand words. On the same day that I made the change, the child said down stairs down stairs green block then bolted to the door. He pulled as hard as he could on the doorknob but did not have the dexterity to turn it. If he had not said what he wanted, I would not have opened the door. I would have assumed he was trying to escape from the session. In the therapy area downstairs, he walked straight to the game cabinet and pulled out a cardboard box from the middle of the shelf, not even fazed by all the games he knocked down in the process. He flipped open the lid and picked out all the green magnetic shapes, then started stacking them in different ways. Before today, down would have been the only word of that phrase he could have said. How long had he been wanting to tell me the exact game he wanted to play? How long had he been pulling on doorknobs trying to lead me to what he wanted, not to try running away? I could not wait to share this great breakthrough with his mom at the end of the session.

Some parents, and even some professionals, assume that kids with significant disabilities know very little or are too difficult to teach. In my experience, many professionals just didnt know how to give them the opportunity to learn and discover their potential or didnt stick something out long enough to give it a real chance. For all children, belief in their potential makes a huge difference in their learning. But for kids using AAC, belief in potential is everything. If the therapist or parent does not truly believe in the childs potential, they physically limit what is possible for the child to say by only giving them a few options. When professionals set the bar low with AAC, the child will be stuck.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «How Stella Learned to Talk»

Look at similar books to How Stella Learned to Talk. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book How Stella Learned to Talk and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.