The Linda Schele Series in Maya and Pre-Columbian Studies

THE ADORNED BODY

Mapping Ancient Maya Dress

EDITED BY

NICHOLAS CARTER,

STEPHEN D. HOUSTON,

AND FRANCO D. ROSSI

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

AUSTIN

Copyright 2020 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

First edition, 2020

This series was made possible through the generosity of William C. Nowlin Jr. and Bettye H. Nowlin, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and various individual donors.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

utpress.utexas.edu/rp-form

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Carter, Nicholas (Anthropologist), editor. | Houston, Stephen D., editor. | Rossi, Franco (Anthropologist), editor.

Title: The adorned body : mapping ancient Maya dress / edited by Nicholas Carter, Stephen Houston, and Franco Rossi.

Description: Austin : University of Texas Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019057919 | ISBN 978-1-4773-2070-9 (cloth) | ISBN 978-1-4773-2072-3 (ebook) | ISBN 978-1-4773-2071-6 (ebook other)

Subjects: LCSH: MayasClothing. | Clothing and dressMexico. | Clothing and dressCentral America.

Classification: LCC F1435.3.C69 A43 2020 | DDC 391.00972/6dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019057919

doi:10.7560/320709

Contents

STEPHEN D. HOUSTON, NICHOLAS CARTER, AND FRANCO D. ROSSI

NICHOLAS CARTER, ALYCE DE CARTERET, AND KATHARINE LUKACH

KATHARINE LUKACH AND JEFFREY DOBEREINER

NICHOLAS CARTER AND ALYCE DE CARTERET

FRANCO D. ROSSI, KATHARINE LUKACH, AND JEFFREY DOBEREINER

NICHOLAS CARTER

MALLORY E. MATSUMOTO AND CARA GRACE TREMAIN

ALYCE DE CARTERET AND JEFFREY DOBEREINER

FRANCO D. ROSSI AND ALYCE DE CARTERET

CARA GRACE TREMAIN

MALLORY E. MATSUMOTO

STEPHEN D. HOUSTON, FRANCO D. ROSSI, AND NICHOLAS CARTER

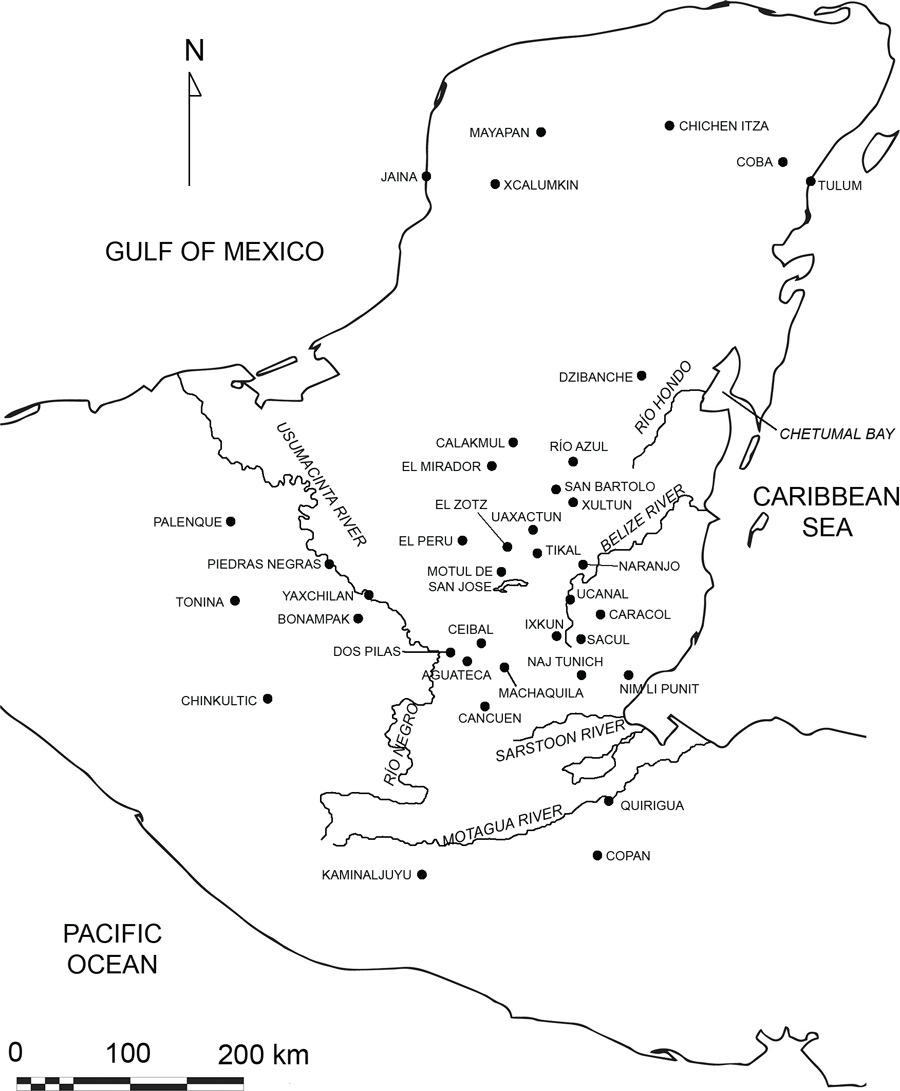

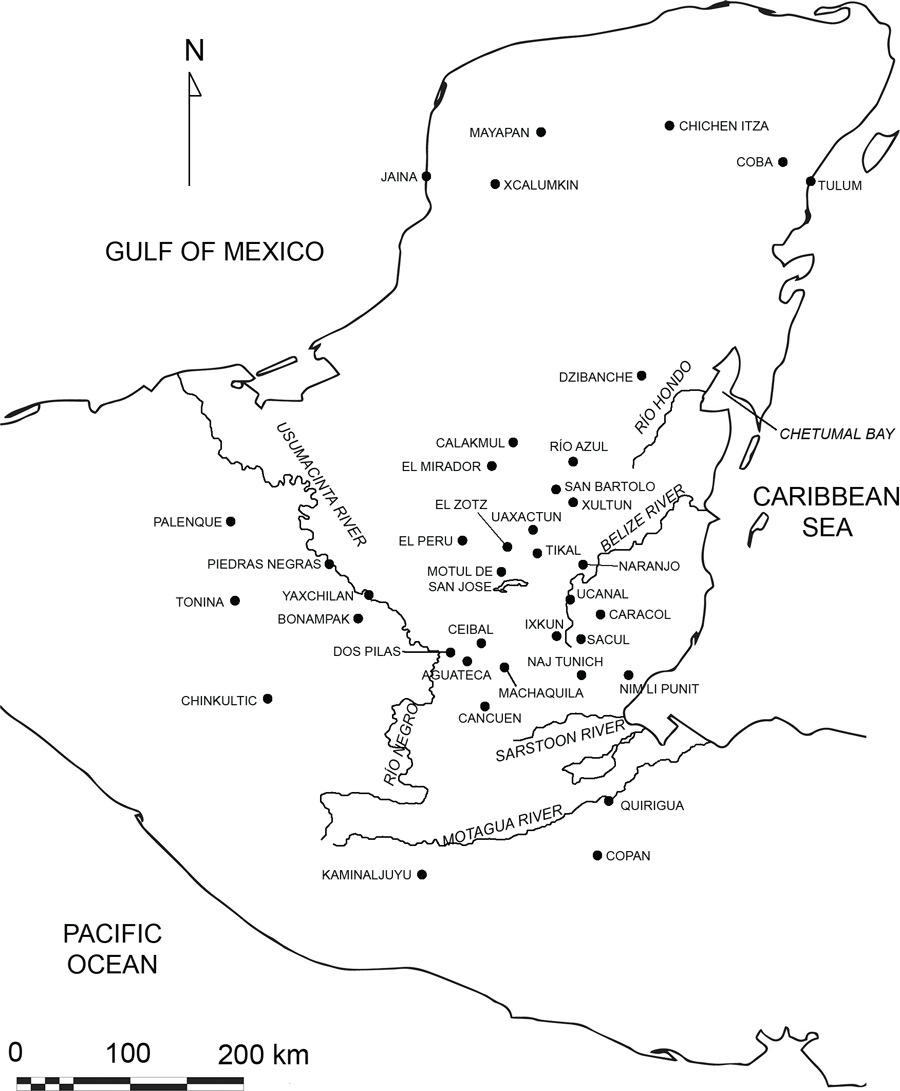

FIGURE 1.1. The Maya region. Map outline courtesy of Clifford Brown and Walter Witschey.

CHAPTER 1

The Adorned Body

STEPHEN D. HOUSTON, NICHOLAS CARTER, AND FRANCO D. ROSSI

The human body is a key vehicle for expressing status and identity. Subject to external influence and internal motive, it declaims, moves, receives, and does. Yet the most flexible conduit of meaning is not the human frame itselfonly so much can be done to physique. It is what the body wears, holds, and supports. By working through such projections of role and identity, this book offers a synthesis of dress in ancient Maya civilization, with special emphasis on the rich evidence from the Classic Maya who lived in or near the Yucatn Peninsula through much of the first millennium AD ().

What is dress? To our view, it is the full array of objects, coverings, clothing, pelts, regalia, footwear, pectorals, headdresses, ear ornaments, belts, bracelets and anklets, body paint, and haircuts, as worn, held, or otherwise displayed on the human frame. These features are widely noted, excavated, and documented in images and archaeological corpora. Yet in the Maya case, there are thorough explorations of body concepts (e.g., Houston, Stuart, and Taube 2006), but relatively little is known about items of dress as separate things within ensembles (for useful if more broadly articulated exceptions, see R. Joyce 2001; and Orr and Looper 2014). There is little systematic literature on why these elements were worn, when, or by whom. Nor are there, outside of studies covering artifacts from particular cities, synthetic studies about such classes of objects, what they were made of, or how they might be grouped and separated (for site-based artifact studies, see Kidder 1947; T. Lee 1969; Moholy-Nagy 2003, 2008; Sheets 1983; Taladoire 1990; Taschek 1994; Willey 1965, 1972, 1978; and Willey et al. 1994). There is insufficient understanding about how these features changed over time and how they varied from site to site. Other parts of the world seem more attentive to these matters (Callmer 2008; T. Martin and Weetch 2017), sometimes under the purview of fashion, an intersection of aesthetic value, social competition, and personal caprice that continues to animate the walkways of Paris and elsewhere (Welch 2017). In Mesoamerica, the most comprehensive research comes from decades past (Anawalt 1990), with some strong additions in recent years (e.g., Olko 2005, 2014; Orr and Looper 2014).

To theorize dress, there is necessary guidance from comparative research (Hansen 2004). Influential sources suggest the following: (1) structures of power and the subjugation of individuals control the use of dress (Foucault 1995); (2) identity and boundary definition between self and society infuse ideas about what to wear (Strathern 1979; Turner 2012); (3) clothing and personal ornament bear complex, multivalent meanings, albeit with a foundation in basic themes such as gender, age, and so forth (Doniger 2017; Twigg 2015); (4) competition in royal courts and societies in elite contact tends to generate similarities and contrasts (Elias 1978); (5) dress, in the sense of body arts that modify human appearance, builds on historical practices that people must learn (The body is mans first and most natural instrument [Mauss 1973, 75]); (6) dress is always about wider change in relations of human inequality and unstable statusindeed, it not only symbolized change but became a vehicle for change (P. Martin 1994, 426); and (7) people copy others and enforce or self-enforce manners of behavior by citing or imitating those models (Butler 1990, 1993). Lurking behind these issues of choice and control is sumptuary law or tradition, by which certain dress or its coloration or material might be thought appropriate or not, depending on moral precepts and specified attributes of class or status (Anawalt 1980; Elliott 2008; Hunt 1996; Shively 19641965). Among the Maya, a jaguar pelt is known to have been worn by royalty, much as, for the Tudors of England, cloth of gold, an exceedingly expensive material, was intended for royalty, magnates, or prelates. Yet the ideal cedes to reality in most places. Much evidence suggests that sumptuary guidelines are often ignored and almost never enforceable. But such laws and rules do serve as ever-shifting projections of societies yearning for external tokens of social status (Hayward 2009, 27, 75).

Scholars such as Marcel Mauss, Michel Foucault, and Judith Butler are important influencers at this point, albeit with some reservations. In general, for all the many insights about how humans control one another through norms, subjugation, and mutual citation, Mauss, Foucault, and Butler blunt the effects of personal preference and reduce the possibility of choices and whims unconditioned by the dictates of others (Houston 2018a, 713). This does not deny the centrality of their ideas to understanding dress or their ability to envision historical and cultural evidence in useful ways. Still, it may be that the way forward is less through broad theorizing than in the engrossing details of past and present arts of the body (e.g., for dance and gesture: Kaeppler 2011; McNiven 2000). These approaches have their own limitations. Of late, for example, body arts seem generally to coincide with studies of tattooing, masking, or altering the skin (e.g., N. Thomas 2014). Does this only reflect current aesthetic practices among the young today, or might we explore how physical adjustments send loud and even subversive messages in antiquity as well? Writing about such arts, Nicholas Thomas looks with special intensity at the discontents, outliers, hybrids, liminal, and criminally variant (e.g., 2014, 139173). In any human enterprise, absolute conformity, the desired aim of despots, is impossible to elicit or implement. Nonetheless, the royal imagery that grounds this book is by definition about a certain consistency of controlled representation. The work of official display is an earnest business, disinclined to capricious or insubordinate gestures.

Next page