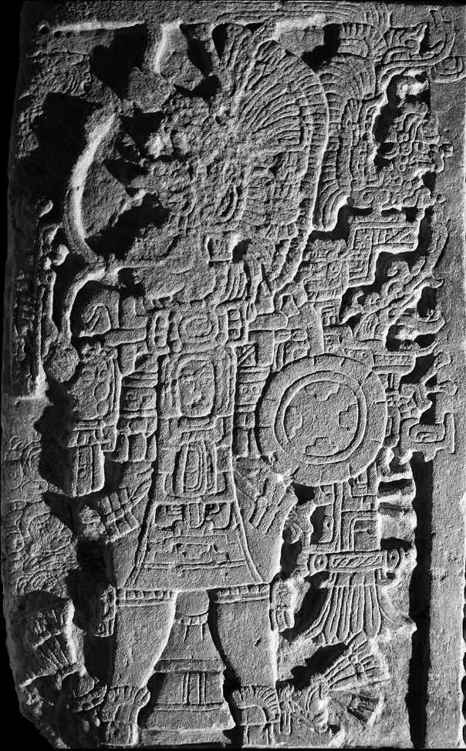

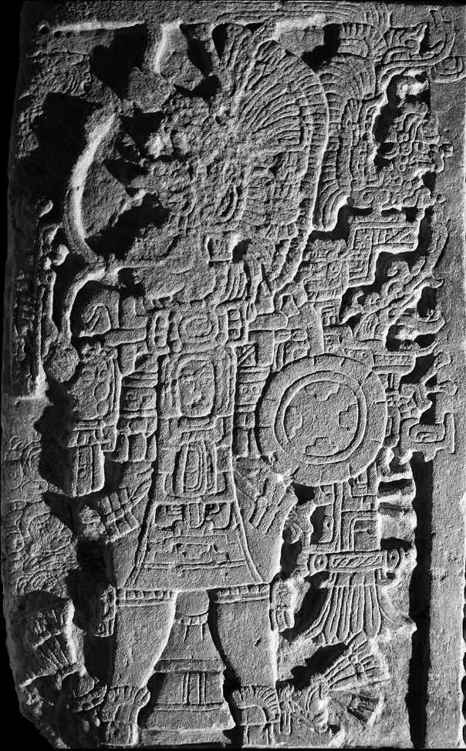

FRONTISPIECE Figure of a dancing king from a wall panel in Structure I3R-5, La Corona, Guatemala. Dedicated 28 October AD 677, this image shows a local ruler, vassal of the powerful dynasty of Calakmul. He wears an elaborate back ornament, labeled paat pihk, back-skirt. Such ornaments often appear with depictions of the dancing Maize God, perhaps alluding to cosmic and geographical motifs. In this back-skirt, the Principal Bird Deity perches on a symbol for sky, from underneath which emerges a snake, an emblem of Calakmul.

Ancient Peoples and Places

Founding Editor: Glyn Daniel

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Breaking the Maya Code

Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs

Angkor and the Khmer Civilization

India: A Short History

The Incas

The Aztecs

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

PREFACE

It has been almost fifty years since the first edition of The Maya appeared. Michael Coe wrote the book in the belief that the time was ripe for a concise and accurate, yet reasonably complete, account of these people that would be of interest to students, travelers, and the general public one, preferably, that could be carried in the pocket while visiting the stupendous ruins of this great civilization. In all subsequent editions, he has tried to keep to these goals. As the decipherment of the hieroglyphs proceeded, it became possible to let the Maya express themselves in their own voice, as the previously mute inscriptions began to speak. With that aim in mind, and to represent a younger generation, Coe has brought on board a co-author, Stephen Houston, his student at Yale and another authority on Maya writing and civilization.

In the last decade, the pace of Maya research has quickened to an extraordinary extent. Hardly a week goes by without the announcement of a new royal tomb or discovery, especially at the close of the dry season, when such finds tend to be made. Based upon new research exploring Maya glyphs and iconography, as well as upon technological advances in fields such as remote sensing and paleonutrition, major archaeological advances have been made in Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras. We now know a great deal about how to conceptualize Maya societies as the seats of royal courts. Coming into view, too, are the founding fathers of such ancient cities as Copan and El Zotz, and the places from which they came. The historical role of Calakmul looms far larger than imagined by earlier researchers, as does the relative independence of zones like coastal Belize, or the varying nature of societies in areas less endowed with inscriptions. Palenque, which has a history of archaeological investigation reaching back into the eighteenth century, now seems to have had a mighty king (Ahkal Mo Nahb); nothing more to us than a name a decade ago, this ruler was responsible for some of the greatest sculptural art ever produced by the Maya. Perhaps the most exciting new developments in scholarship center upon San Bartolo, in the forests of northeastern Guatemala, where amazing murals dating back two millennia have been discovered the oldest Maya paintings yet known or in sites nearby, such as Holmul and Xultun, celebrated in recent years for their glyphic texts, paintings, and monumental stuccos; Calakmul, with its unique murals of everyday life in a large market; and Ek Balam, an extraordinary site in Yucatan with long painted texts and some of the most astonishing stucco reliefs ever found. These elite remains are matched by an ever more sophisticated understanding of environmental change and modest settlement at places around Xunantunich, Belize, Chunchucmil in Yucatan, or the ancient kingdom of Palenque and its neighbors. Yet some puzzles still remain to be solved: above all, the nature of Preclassic civilization, the features of Maya society in Highland Guatemala, and what really happened during the transition between the Classic and Postclassic periods. Was there truly a Toltec-Maya occupation of the huge site of Chichen Itza? Unfortunately, until the day that Chichen becomes treated more as a major site crying out for broad-scale excavation, and less as a venue for mass tourism, those questions will not be answered.

Here we have relied on the advice and learning of numerous colleagues, including those who have recently passed away, especially Pat Culbert, Peter Harrison, Barbara Kerr, Juan Pedro Laporte, Enrique Nalda, Juan Antonio Valds, and Houstons first professor of all things Maya, Robert Sharer. We are particularly indebted to Thomas Garrison, Takeshi Inomata, and Scott Simmons, who gave useful comments on many points in the manuscript. Others on whom we have relied for new information (but they may not always know this!) are Jaime Awe, Tim and Sheryl Beach, Marcello Canuto, Arlen and Diane Chase, Ramn Carrasco, Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos, John Clark, George Cowgill, Francisco Estrada-Belli, Claudia Garca-Des Lauriers, Charles Golden, Heather Hurst, Scott Hutson, David Joralemon, Justin Kerr, Brigitte Kovacevich, Rodrigo Liendo Stuardo, Simon Martin, Sam Merrin, Mary Miller, Sofa Paredes Maury, Jorge Prez de Lara, Michelle Rich, Rob Rosenswig, Frauke Sachse, Catharina Santasilia, William Saturno, Andrew Scherer, David Stuart, Karl Taube, Alex Tokovinine, Ben Watkins, David Webster, Brent Woodfill, Marc Zender, and Jarosaw raka. However, if there are mistakes in this book, they are ours alone.

A word about words: here, glottalized consonants are indicated by a following apostrophe (as in kahk, fire). The only exceptions to these new rules will be the names of sites so well known in the literature, and to students and tourists, that it would be confusing to change their spelling (such as Tikal, which logically ought to be Tikal). Throughout, vowels have about the same pronunciation that they have in Spanish; long vowels are indicated by doubling, as in muut, bird, a feature that has, with other sounds, been detected over the last decade or two in Maya writing. Unglottalized consonants are pronounced approximately as in English, with these exceptions:

| the glottal stop (in initial position, or between two vowels); it most closely resembles the tt in the Cockney English pronunciation of bottle |

| h | a glottal fricative, as in German ach or Bach |

| q | a postvelar stop, like a guttural k, restricted to highland Mayan languages |

| tz | a voiceless sibilant consonant, with the tip of the tongue held against the back of the teeth |

| x | like English sh |

Certain of the words that the reader will encounter here are in Nahuatl, the national tongue of the Aztec state, which was a great trading lingua franca at the time of the Spanish Conquest (recent research also points to the influence of its linguistic cousin, Pipil). Nahuatl names were transcribed in Roman letters in terms of the language spoken by the conquistadores of the sixteenth century. Neither they nor Maya names have been accented here, since both are regularly stressed: Maya ones almost always on the final syllable, and Nahuatl ones on the penultimate. Note, too, that the names of Mayan languages have recently changed, often after consultation with local speakers []. Yet this can also lead to confusion: Yukatekan refers to a set of related languages, Yucatecan to an area.