Art and Myth of the Ancient Maya

Art and Myth of the Ancient Maya

Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos

Published with the assistance of the Frederick W. Hilles Publication Fund of Yale University.

Copyright 2017 by Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

yalebooks.com/art

Designed by Leslie Fitch

Library of Congress Control

Number: 2016940998

ISBN 978-0-300-20717-0

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

Jacket: Mural painting, Las

Pinturas Sub-1, San Bartolo, Guatemala (details of )

Frontispiece: Quirigu Stela C.

Photograph by Alberto Valdeavellano, ca. 1915 ()

Para mi esposa, Silvia, y mis hijos, Oswaldo Esteban y Ana Silvia, con amor

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My research on Mesoamerican myths began during my tenure as curator of the Museo Popol Vuh, where I had the privilege of working with an outstanding collection of ancient Maya ceramic vessels with mythical representations. This book builds partly on a previous volume I wrote, Imgenes de la Mitologa Maya (2011), which delved into the mythical themes represented on selected objects from the Museo Popol Vuh collection. The contents of also incorporate content from articles that I published previously in the journals Ancient Mesoamerica, Estudios de Cultura Maya, and Estudios de Cultura Nhuatl.

A Junior Faculty Fellowship from Yale University allowed me to devote adequate time to write this book, which is published with assistance from the Frederick W. Hilles Publication Fund of Yale University. I owe special thanks to Justin Kerr, who waived all charges for his photographs to honor the memory of his late wife, Barbara. Jorge Prez de Lara, Michel Zab, Nicholas Hellmuth, Dmitri Beliaev, Dennis Jarvis, Inga Calvin, Guido Krempel, Ins de Castro, and Hernando Gmez Rueda also allowed me to reproduce their valuable photographs. For similar reasons, I thank Daniel Aquino, director of the Museo Nacional de Arqueologa y Etnologa in Guatemala City; Diana Magaloni and Megan ONeil, from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and Susana Campins, from the Museo Vigua de Arte Precolombino y Vidrio Moderno in Antigua Guatemala. I am thankful for the assistance of Juan Antonio Murro at Dumbarton Oaks, and Mara Teresa Uriarte and Teresa del Roco Gonzlez Melchor at the Instituto de Investigaciones Estticas unam). In addition, Bruce Love, Heather Hurst, Lucia Henderson, David Stuart, Alexandre Tokovinine, and Christophe Helmke allowed me to reproduce their fine artwork, while Leticia Vargas de la Pea shared unique images from Ek Balam. Valentina Glockner Fagetti and Samuel Villela Flores kindly shared unpublished narratives that were especially relevant for this book. Numerous colleagues and friends provided comments and insights or contributed in various ways to this volume, although the final outcome is my sole responsibility. I thank Brbara Arroyo, Karen Bassie-Sweet, Edwin Braakhuis, Claudia Brittenham, Laura Alejandra Campos, Vctor Castillo, Michael Coe, Jeremy Coltman, Enrique Florescano, Julia Guernsey, Christophe Helmke, Stephen Houston, Timothy Knowlton, Alfredo Lpez Austin, Camilo Luin, Mary Miller, John Monaghan, Jesper Nielsen, Barbara de Nottebohm, Guilhem Olivier, Dorie Reents-Budet, Karl Taube, Alejandro Tovaln, Ruud van Akkeren, and Erik Velsquez. At Yale University Press, I thank Katherine Boller for her enthusiastic welcome to my proposal, and Tamara Schechter, Heidi Downey, Sarah Henry, and Laura Hensley for their editorial input.

NOTE ON TRANSLATIONS AND ORTHOGRAPHY

To a large extent, my arguments depend on the accuracy of translations from numerous Mesoamerican languages. I employed the available editions of colonial texts and modern narratives, and whenever possible I contrasted translations of important passages. For the Popol Vuh, I used the modern English translations by Dennis Tedlock and Allen J. Christenson. Especially useful were Christensons and Munro Edmonsons transcriptions with parallel translation, and Michela E. Craveris recent Spanish translation, which features abundant lexical notes. In this volume, I quoted passages from both Tedlocks and Christensons translations, while providing alternate translations in the endnotes.

Following usual conventions used in Maya epigraphy, transliterations of hieroglyphic collocations appear in boldface, using lowercase for syllabic signs and uppercase for logograms. Transcriptions that approximate the reconstructed phonetic spelling of hieroglyphic terms appear in italics.

In general, I respected the orthography of indigenous words in the original sources, instead of opting for modern standardized orthographies. For example, I use the orthography of Francisco Ximnezs manuscript for the names of characters from the Popol Vuh. Unless otherwise noted, I made all translations from Spanish to English.

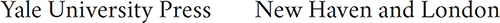

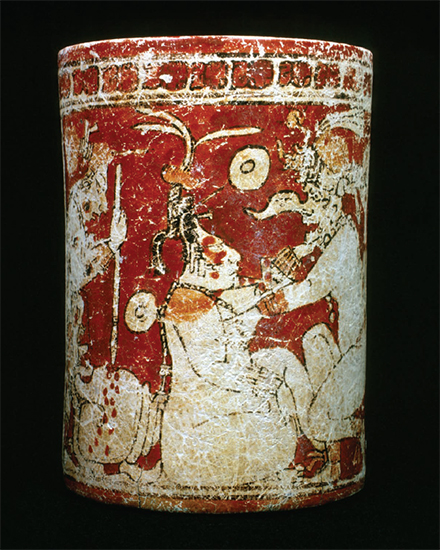

FIGURE 1

The Bleeding Conch Vase, Late Classic, lowland Maya area. Present location unknown.

Introduction

The pale bodies of four charactersperhaps originally fivestand out against the dense, red background of a lowland Maya ceramic vase, created more than twelve centuries ago (). Despite its age, the object preserves considerable detail, except for a section that suffered erosion and, perhaps for that reason, was not recorded in the available photographs. While subtly detailed, the characters are somewhat disproportionate and awkwardnothing can explain the womans left foot showing under her right knee, while the leg is flexed forward. More than anatomical accuracy, the composition is about interaction among the participants, who engage with each other, forming a lively and meaningful scene. There is a story behind these figures involving an old god seated on a throne, a woman who interacts with a long-nosed partner, and a young man with spotted skin. But there is no associated narrative that would help modern observers to reconstruct the unfolding of the story.

In multiple ways, this vasehereafter designated as the Bleeding Conch Vasecondenses the challenges faced by students of ancient Maya mythology. Its original provenance and present whereabouts are unknown. It was likely found in an archaeological site in the Maya Lowlands and extracted by looters who kept no record of its context and associations. Its shape and painting style allow us to date it to the Late Classic period, but we are missing the basic pieces of information that would help archaeologists to derive inferences about the people who created the object, used it, perhaps traded it, and, eventually, placed it in a secluded deposita burial chamber or cache offeringwhere it endured the ages without shattering to pieces.

The painted scene was clearly based on a mythical theme. The trained eye can readily recognize some of the characters as gods and goddesses known from multiple representations, although the overall scene has no exact parallel in the known corpus of Maya art. Like Attic vase painters from ancient Greece, ancient Maya ceramic artists developed an elaborate pictorial language to represent subjects chosen from a rich trove of mythical beliefs and narratives. The participants were gods whose actions created the conditions for life and provided paradigms for human sociality. Their deeds inspired some of the most elaborate examples of Maya ceramic art. Similar topics were sometimes represented on mural paintings and sculptures, but the majority of known depictions are preserved on pottery.

Next page