For Peggy.

And for all the girls.

A reminder to always strive for your dreams.

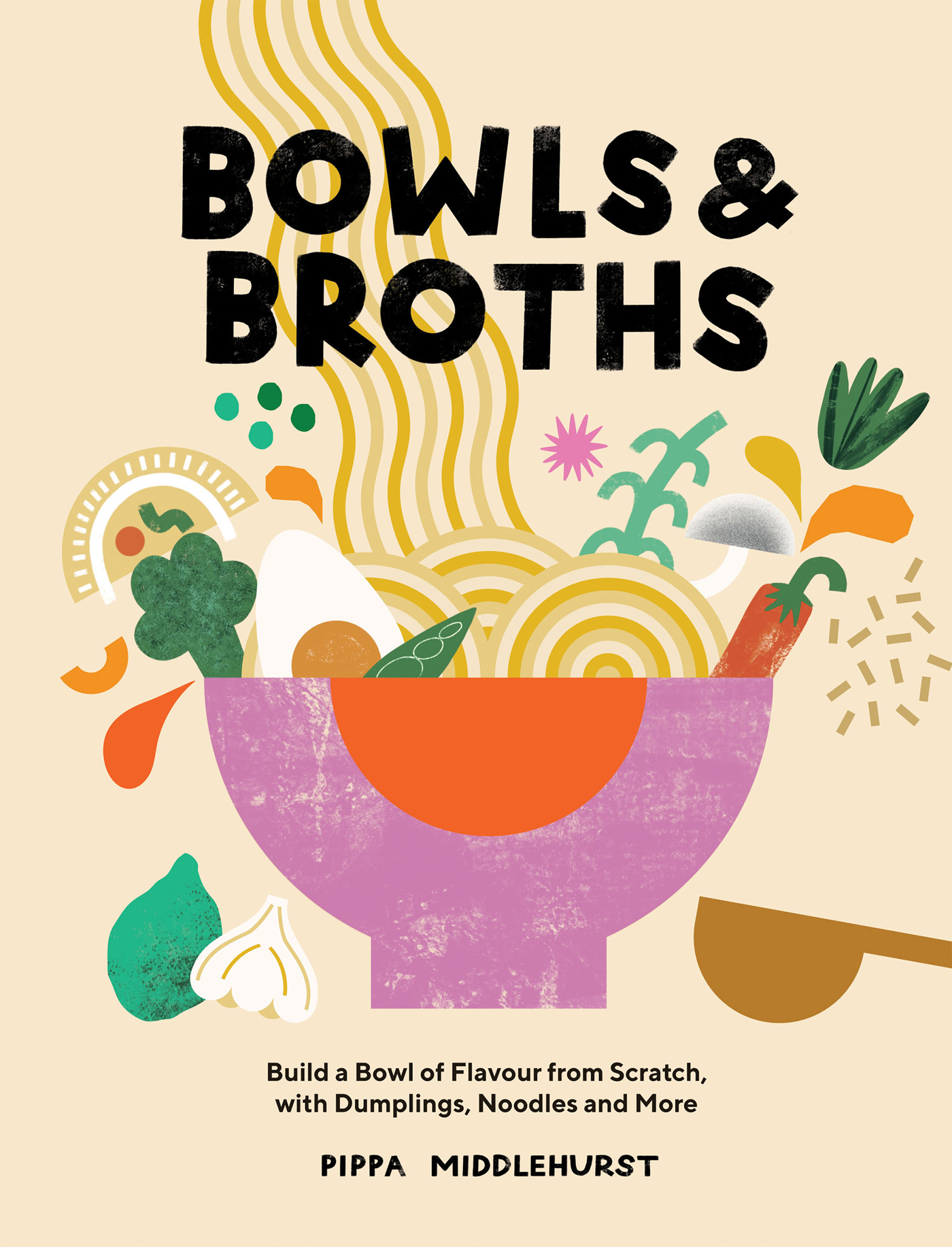

Publishing Director Sarah Lavelle

Editor Stacey Cleworth

Art Direction and Design Emily Lapworth

Cover and Illustrations Han Valentine

Photographers India Hobson & Magnus Edmondson

Food Stylist Rob Allison

Prop Stylist Beck Hanson

Head of Production Stephen Lang

Production Controller Nikolaus Ginelli

First published in 2021 by Quadrille, an imprint of Hardie Grant Publishing

Quadrille

5254 Southwark Street

London SE1 1UN

quadrille.com

Text Pippa Middlehurst 2021

Photography India Hobson & Magnus Edmondson 2021

Design and layout Quadrille 2021

All rights reserved. No part of the book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The rights of Pippa Middlehurst to be identified as the author of this work have been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988.

Cataloguing in Publication Data: a catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 78713 777 6

Ive always preferred eating from a bowl.

A large, deep bowl, the flavours of the ingredients already melded, ready and waiting to go. Uncomplicated eating.

At a table, in bed, curled up in an armchair, however I choose. A close second in the running for favourite flavour vessel is one that also provides one perfect mouthful after another the sandwich. But that is a different book entirely.

The recipes in this book grew from a particular method that initially stemmed from fridge and freezer forages, or experiments in my home kitchen, usually while hungry. The findings of my forages, often humble ingredients, built and layered in such a way to create something sublime. And almost always sloshed into a large bowl.

I might find a simple chicken stock in the freezer, originally intended for wonton noodle soup. The jackpot! What a find! A simple stock has endless possibilities. I would begin by seasoning the bowl adding the building blocks of flavour directly to the bowl I would eat out of.

Indulging my appreciation and enthusiasm for East and Southeast Asian flavours, I might choose some spicy, fermented doubanjiang, a little light soy sauce and black rice vinegar, a touch of sugar and some sour pickled mustard greens to add to the bowl. Pour in the hot stock to combine. Top with wheat noodles, a soft-boiled egg and a has-seen-better-days sliced spring onion (scallion). Or, whatever I had on hand.

Throughout these forages, building and layering from the bottom up, I found I was repeating the same pattern. As a molecular biologist by trade, repetition will always lead me to an efficient methodological process, from which a reliable formula appears.

This technique is not new, of course. Plenty of street-food vendors in East and Southeast Asia, from Taiwan to Thailand, cook this way. Endless individual bowls of sauce, seasoning, crunchy bits, fresh bits, herbs, aromatics, a starch, a protein all neatly laid out on a street cart or stall and rapidly tossed into a bowl, with a lightning-fast flick of the wrist, landing in a melamine bowl in perfect, complementary amounts.

In Japan, for example, a flavourful tare sauce is added to the bowl prior to ramen broth, then noodles and toppings are added. All the ingredients brought together at the final moment, to maximize on their freshness, to layer and develop complexity of flavour.

As with this technique, the ingredients and combinations used in this book are inspired and informed by years of learning and experimenting with ingredients, techniques and flavours from across East and Southeast Asia, and powered by a deep love and respect. The areas of East and Southeast Asia represent a multitude of cultures and cuisines and the ingredients, skills and flavour combinations I draw upon here barely represent the tip of the iceberg. And while nothing can replace a lived experience, or growing up with home-cooked East and Southeast Asian food, I feel extremely lucky and happy to have been able to learn about these cuisines from a distance, researching and practising, over the years.

If youre interested in further reading, Id thoroughly recommend Silk Road Recipes: Parida's Uyghur Cookbook, by Gulmira Propper, which explores the cuisine of the Uyghur people of Northwest China, and Chicken and Rice: Fresh and Easy Southeast Asian Recipes From a London Kitchen by Shu Han Lee. My favourite TV chef growing up was Ching-He Huang I have all her cookbooks. Online, I am a big fan of The Woks of Life (@thewoksoflife), a family-run Chinese recipe blog its full of amazing recipes, including so much research. Red House Spice (@red.house.spice), a blog run by recipe developer and photographer Wei, who also runs culinary tours of China and has become a friend, is a massive inspiration. And, I've learned so much from the recipes and writing of Grace Young (@stirfryguru), especially her book The Wisdom of the Chinese Kitchen.

The recipes I share here are largely non-traditional happy accidents that made it into my regular repertoire, dishes created for supper clubs or homages to the classics adapted for my home kitchen. Regardless, theyve all brought me comfort and satisfaction beyond measure and I hope theyll do the same for you.

Its not necessary to know the ins and outs of the science behind a good broth to actually make a good broth thats why we have recipes. But if your mind works anything like mine, then it certainly doesnt hamper the process.

Flavour is the entire experience the taste, smell and texture of a food. Taste, on its own, is rarely satisfying without aroma. Textures pleasure is fleeting and a great-smelling meal is a tease if you cant taste it, too. So, in learning to prepare a delicious bowl, full of perfect mouthfuls, we must learn to layer all these components and balance them to create harmonious flavour. Understanding this formula is key, and gives the tools needed to begin experimenting.

TASTE

Taste and smell are activated by different molecules and compounds, and these are all received differently by the receptors in our nose and mouth. Taste is received by the tongue, and salty, sweet, sour, bitter and savoury are delivered by molecules of sugar, salt, sour acids, amino acids and alkaloids. Interestingly, some sensations are not in fact tastes at all the heat we feel from chillies, for example, is actually received by pain receptors, but we perceive this as a form of taste.

Furthermore, our tongues and mouths experience protein, fat and carbohydrates differently, and compounds are received by our receptors in different ways, depending on how theyre travelling. Because fats hold onto aroma molecules, they transport them better. So if the flavour of roasted garlic and Sichuan pepper travels into your mouth riding on the back of a chicken fat molecule a fat molecule being the safest and most reliable form of transport for a flavour molecule its not only going to