The Kinsey Institute

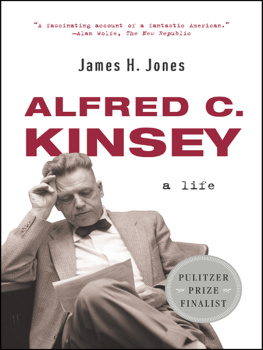

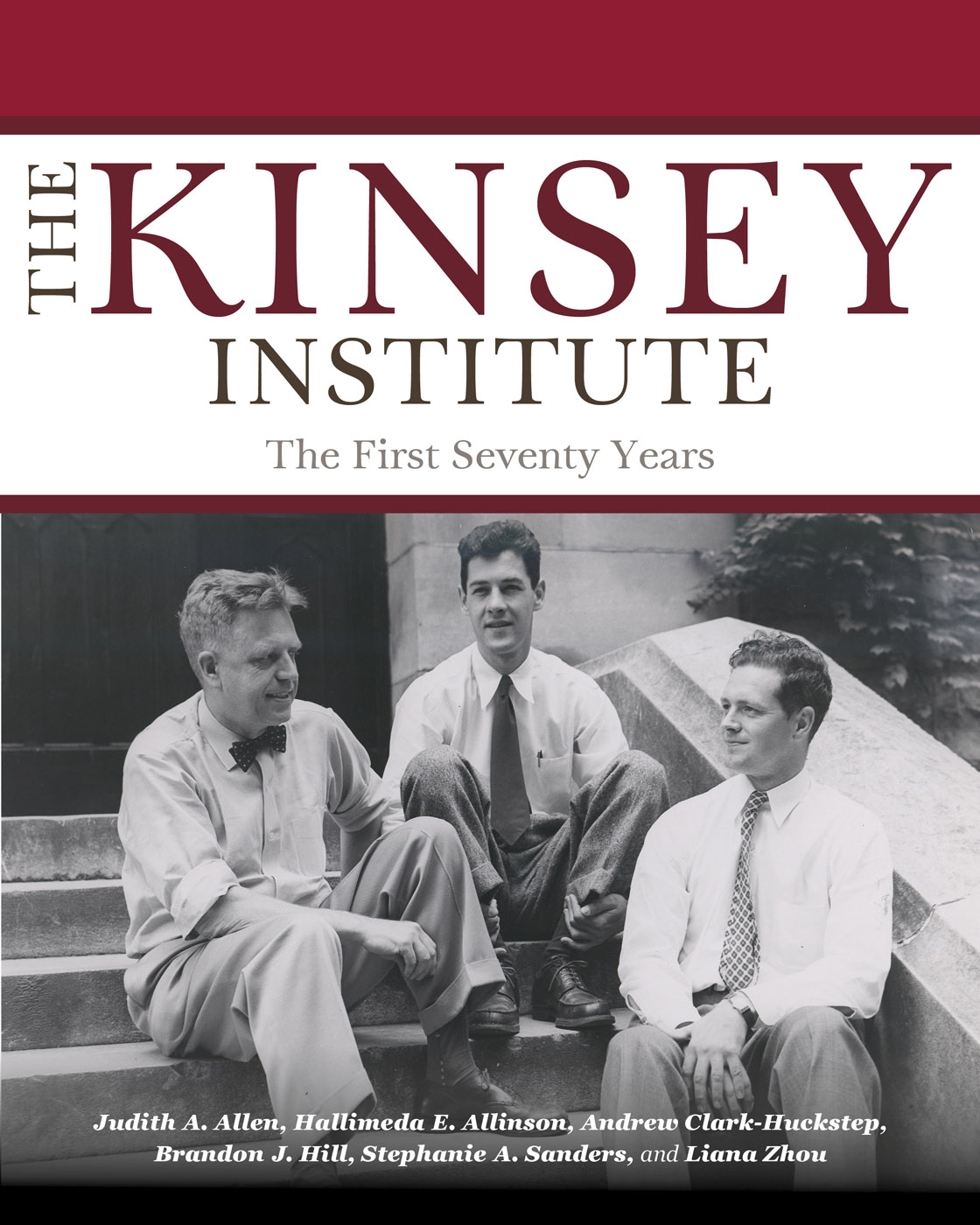

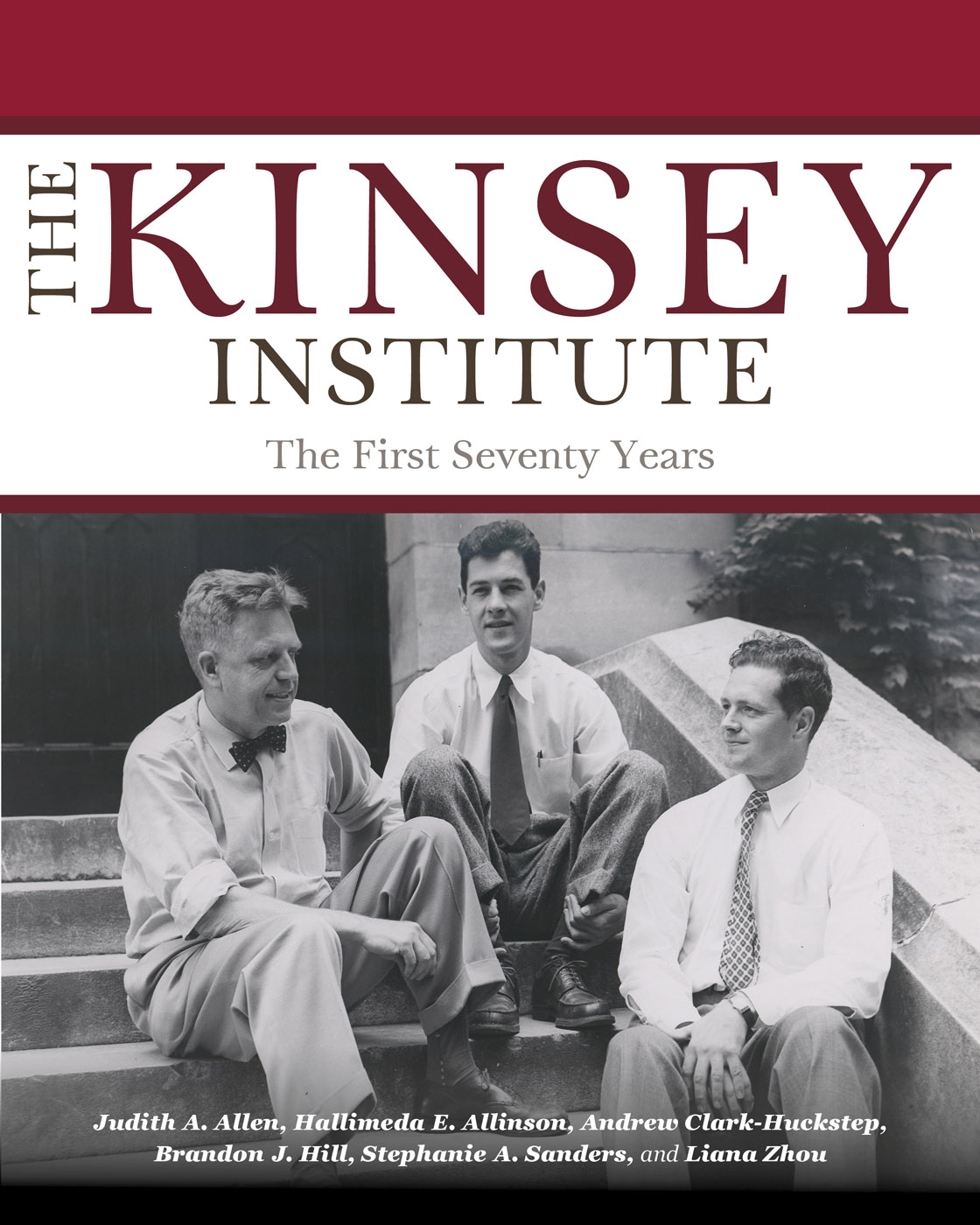

Alfred Charles Kinsey. Clarence Tripp took this photograph around the time that Sexual Behavior in the Human Male was published, ca. 1948. Photo courtesy of Kinsey Institute Library and Special Collections.

THE

KINSEY

INSTITUTE

The First Seventy Years

JUDITH A. ALLEN

HALLIMEDA E. ALLINSON

ANDREW CLARK-HUCKSTEP

BRANDON J. HILL

STEPHANIE A. SANDERS

LIANA ZHOU

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2017 by Indiana University Press

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-02976-8 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-253-03023-8 (e-bk.)

1 2 3 4 5 22 21 20 19 18 17

For Wendy Kinsey Corning

Contents

Acknowledgments

It is a pleasure to have so many people to thank for this short history reaching fruition. None of us realized that this project was in our futures. Sue Carter, director of the Kinsey Institute, wanted to mark, for 2017, the seventieth anniversary of the Institutes founding. The historians amongst us realized promptly that existing Kinsey biographies or histories of American sex research did not suffice for the purpose. Too many unanswered questions loomed, and, it seemed, too much missing evidence prevented us from providing convincing explanations of key matters. Whose idea was it to found the Institute? Was it Indiana Universitys reliably visionary new young leader, President Herman B Wells? Was it Kinsey himself? What was its founding rationale or purpose? How was it structured, governed, and resourced? How did the university town of Bloomington, the state of Indiana, and the United States respond to this institutionalization of the field of sex research, hitherto of European rather than American genealogy? Further, if earlier Kinsey biographies and the 2004 Bill Condon movie, Kinsey, provided some sense of the Institutes research activities while it was led by Kinsey, the period from his 1956 death until the present, for most people, was much less clear.

Several researchers had done previous work touching one way or another on the story of the Institutes founding, early work, and activities. A seventieth-anniversary assessment, though, warranted something more systematic. It involved searching from top to bottom not only the Institutes extensive germane collections but also the Indiana University Archives, President Herman B Wellss papers and correspondence, the archives of the Rockefeller Foundation and other granting bodies, and the papers of key figures in American sex research and related clinical fields in Boston, Cambridge, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC. These efforts garnered new documents, images, and texts. Some of this information came to be used for hallway display in the Institute premises and for booklets for visitors, guests, and sponsors of the Institutes work and collections.

Yet the materials we collected and appraised illuminate beyond these anniversary purposes. They permit deeper understanding, as well as fresh perspectives on the founding and subsequent development of the Institute. As we began to grasp the implications of these newly discovered records, it seemed that the seventieth anniversary presented an opportune moment to attempt to assemble a short history of the founding and further work of the Institute across its first decades. Each of us had undertaken research related to or had been associated with periods of the Institutes history. So, almost in the spirit of an experiment, each of us undertook to write first-draft chapter(s) on eras, phases, or sections of Institute history that we knew best. Then, once we could see what we had, we would revise toward a single narrative.

Historians often regard institutional histories as tedious affairs, and rightly so. Since these histories are semisponsored or maybe sullied by the whiff of being an in-house infomercial, the advance verdict can be guilty. Of what? Boosterism. They sometimes advance an apologist voice, an unbalanced papering over, perhaps, of the problems, scandals, and mistakes. We hope we have found ways to avoid these pitfalls. Our individual histories as students, scientists, and scholars, all differently affiliated with the Institute, mean that we are committed to its most effective possible future while regretting its inglorious phases and conditions of difficulty. Yet our different generational and structural relationships with it provided us with resources to balance and critically scrutinize the perspectives we initially represented. Our collaboration involved combining our drafts into one text, then scrutinizing and revising as a whole. We asked each other hard questions. And we reached new insights from these exchanges, some of us changing our minds on issues along the way either in the light of new evidence or from the recasting of that evidence by coauthors with experience of matters narrated. We hope that these approaches and dynamics have helped us to avoid too official a history of the Institute. Of course, this judgment ultimately belongs to our readers.

We are indebted to the Kinsey Institute collections staff for the privilege of working with the archives and manuscripts and, not least, their invaluable assistance in navigating them. Shawn C. Wilsons knowledge of the collections and endless patience with our questions proved beyond amazing. He could not have been more generous with his time or assistance. Taylor Dean, Rachel Schend, Jack Kovaleski, and Kendra Werst tirelessly helped locate files, scan documents, and research a variety of questions, often under difficult circumstances. Anne Jones selflessly volunteers her time to help maintain the condition of the archives. We also found a warm welcome and indispensable assistance in our forays into Indiana University Archives, with its many relevant collections. Our deepest gratitude too is owed to the diverse special collections staff of many archives and repositories farther afield, including the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America and the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard University, as well as at Indiana University and its community. For their special assistance, we thank Saundra Taylor, Moya L. Andrews, Zachary Clark-Huckstep, Diana Carey, and Wendy Kinsey Corning.

Like all authors reaching this point, we owe a trail of debts to many people associated with Indiana University Press. Raina Polivka, on the eve of her departure to the University of California Press, encouraged us in the design and enlisting of this book project with the Press. Janice Frisch and Gary Dunham have been the best of editors and coaches, with unfailing faith in our shaggy collective endeavor, even in our moments of pause. Two anonymous readers offered astute and expert commentary, with an array of valuable suggestions, which we have fully embraced in the revision process. Mary M. Hill copy edited with impressive skill, shrewd insight and lightning speed; and Kate Schramm greatly assisted with down-to-the-wire problem solving and elusive details. Meanwhile, Dave Miller and his project team showed us nothing but constructive professionalism and an intriguing blend of cool (in the best sense), patience, and verve, which edged us, partly to our amazement, over the finish line. We vote them all our hearty thanks.

Next page