Contents

Introduction

In February 2013, two things happened: I turned thirty-nine and I joined the National Trust. Other people in my position would have thought Ill hit forty this time next year, Im off on a hedonistic rampage and gone to Ibiza for twelve months. Not me. Its for the best: Im not making a fool of myself in nightclubs, and now we have a nice sticker on our windscreen.

We joined at Chartwell even with my terrible maths, I could see that joining and getting access to 500+ places was better than paying to visit one and I was very excited about it. But months went by and no second outing took place. And when I did finally travel the massive 1 miles from my house to Osterley Park in London, I enjoyed it immensely but couldnt remember anything about it when I got home.

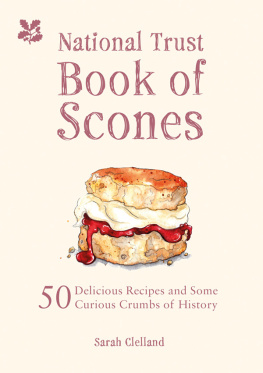

And so I formed a mission: I would travel to every National Trust place. At each one, I would record the most fascinating bits of its history and I would reward myself with a scone. And so the National Trust Scone blog, featuring reviews of both properties and their scones, was born.

Since then, I have visited a lot of National Trust properties. I can tell you that my affection for the Trust has grown and grown. Each property has its own story whether its Moseley Old Hall where Charles II hid under the floorboards, or Clouds Hill where Lawrence of Arabia wrote before his fatal motorbike accident just up the road. Nothing makes me happier than knowing Im going on a little roadtrip to see where Agatha Christie lived, or Anne Boleyn was probably born, or the house at Lyme that stood in for Pemberley in Pride & Prejudice (very popular place for marriage proposals, that last one).

As for the scones my love for those has grown as well. Having eaten 150+ so far, I can let you into the secret of a good one: it has to be freshly baked. It doesnt really matter what recipe you follow (though the official National Trust one used by their cafs is included in this book and comes highly recommended), and it doesnt matter whether you call them scons or sc-owns, or if you put jam or cream on first if they are fresh, it takes a lot to ruin a scone.

Thats why I am delighted that you are the owner (or borrower) of this book. These recipes will ensure that you never run out of ideas for a teatime treat, and if you bake and eat them within a couple of hours, you cant go wrong.

Happy sconeing!

Principles of Scones

Use medium eggs unless otherwise stated

Use whole (full-fat) milk unless otherwise stated

All spoon measurements level unless otherwise stated

Standard spoon measures: 1 tsp = 5ml (5g); 1 tbsp = 15ml (15g)

Oven temperatures are for conventional ovens. If you use a fan oven you may need to reduce the temperature by 10C.

The recipes in this book give instructions for making scones by hand. You may prefer to use a food mixer, especially if you are making larger quantities. The principle is the same whichever way you choose. First you need to distribute the fat evenly throughout the flour: if you are rubbing it in by hand, its best if the butter (or margarine) is chilled and cut into small cubes (or you could grate the chilled fat directly into the flour); using your fingertips, lightly rub the fat into the flour until the mixture looks like fine crumbs; check that its mixed evenly by tapping the bowl any large pieces of fat will rise to the surface. If using a mixer, the fat should be softened before you combine it with the flour. Stir the main ingredient (fruit, cheese, chocolate chips, etc) through the dry mix. Finally, add liquid (milk and/or egg) to bind the mixture to form a soft dough, ready to be rolled out.

Work quickly and lightly throughout. Use a light touch if you are mixing and kneading by hand; if using a food mixer, do not overwork the mixture.

A scone mixture should always include a raising agent: many recipes use self-raising flour, which includes a raising agent, but for added height there is no harm in adding another 1 or even 2 teaspoons of baking powder.

Turn the dough out onto a lightly floured surface to prevent it from sticking. When rolling out the dough, dont press hard as this may prevent your scones from rising to fluffy perfection.

When stamping out the scones, push straight down with the cutter, rather than twisting it; this will encourage the scones to rise evenly. To make it easy to lift the cutter cleanly, put some flour into a small bowl and dip the cutter into the flour before stamping out each scone.

The recipes suggest the size of cutter, but use whatever size you like just bear in mind that small scones will take less time to cook than larger ones, so keep an eye on them as they approach their recommended cooking time so they dont burn.

Choose a baking sheet thats large enough to hold the scones, spaced slightly apart. To prevent your scones from sticking, prepare the baking sheet either by brushing it lightly with butter, margarine or a light cooking oil, or by lining it with greaseproof paper or non-stick baking paper.

Scones need to go into a preheated hot oven: the cooking time is short, so they need to start cooking straight away. Position the shelf just above the centre of the oven.

A good way to tell if the scones are done is to push gently on the top: the scone should feel springy to the touch.

When you take your scones out of the oven, transfer them to a wire rack so they dont sit on the baking sheet soggy-bottom alert.

Always eat scones fresh, on the day of baking.

Tintagel Old Post Office (CORNWALL)

If you had to pick one National Trust property that sums up Great Britain, it would surely be Tintagel Old Post Office. Youve got Tintagel, the ancient, legendary home of King Arthur. And then youve got the Post Office, with queues stretching for several days across multiple counties. Im joking about the queues Tintagel Old Post Office was briefly a post office in Victorian times, so its not actually open for business today. I did see a man in a stovepipe hat whod been waiting for a passport application form for 130 years, though.

It was built between 1350 and 1400 and probably began life as the home of a prosperous yeoman. In the 1870s it became the receiving office for letters, but it has also been a grocers, shoemakers, drapers and family home. Tintagel began attracting a lot of tourists because of its connections to King Arthur, and as a knock-on (or should that be knock-down?) effect, many buildings were demolished and replaced by hotels.

When the almost derelict Old Post Office came up for auction in 1895, a local artist bought it to preserve it, and the National Trust agreed to buy it from her in 1900. Not surprisingly, its now a Grade I listed building, with a famously wavy slate roof that looks as though it might collapse at any moment.

Next page