Contents

Guide

Contents

Taking Tea

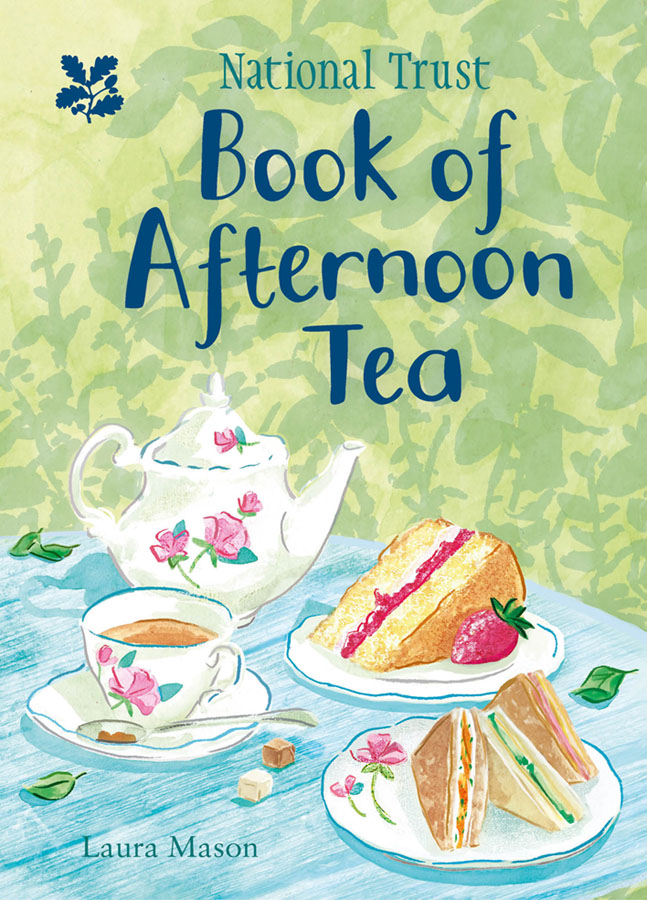

The novelist Henry James, who lived at Lamb House in Rye, East Sussex, between 1897 and 1916, wrote there are few hours in life more agreeable than the hour devoted to the ceremony known as afternoon tea. He did stipulate circumstances, which included an idyllic summer afternoon and a mellow country house.

The former inhabitants of many National Trust houses were keen on afternoon tea and many society hostesses agreed with him. Notable among these were Teresa, the wife of Thomas, the 8th Lord Berwick, at Attingham Park in Shropshire, and Mrs Greville at Polesden Lacey in Surrey. Mrs Greville was especially strict about timing. The meal was served at five oclock, and guests had to be prompt. When Beverley Nichols stayed at the house, he wrote that Tea is at 5 oclock and not at 5 minutes past which means the Spanish ambassador, who has gone for a walk hastily retraces his steps, and the Chancellor of the Exchequer hurries down the great staircase, and that various gentlemen rise from their chaise-longues . Members of the Royal Family were often among the guests, and a room in the house is still known as the Tea Room.

Anna, Duchess of Bedford, found she suffered a sinking feeling in the long, food-free hours between breakfast and dinner.

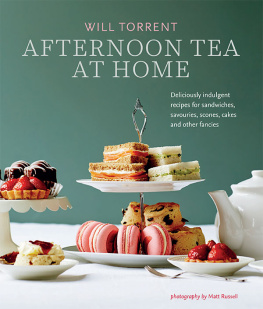

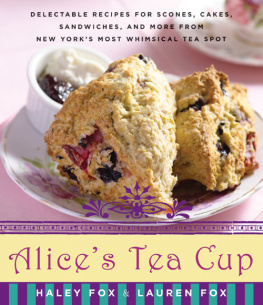

The at home teas of leisured Victorian and Edwardian households were afternoon parties with varying degrees of formality. They featured thin bread and butter (the slices rolled, so as not to soil the kid gloves all ladies wore), little sandwiches, toast cut into fingers, and small cakes. Some houses offered heartier food, such as scones fresh from the oven, and bread to be cut and made into more substantial sandwiches, more appealing to masculine taste. These teas are the inspiration for many now offered in smart cafs and hotels throughout Britain, featuring delicate finger food: tiny sandwiches, pastries, fragile little cakes and biscuits, maybe with scones, or pieces cut from larger cakes, dainty and pretty, as if to say, this is not really a meal.

The history of afternoon tea is obscure; although a few morsels of light food were offered with a drink of tea in the eighteenth century, it is often dated to about 1840, when Anna Russell, Duchess of Bedford, found she suffered a sinking feeling in the long, food-free hours between breakfast and dinner. The latter had become an evening meal in fashionable life (lunch as it is now understood did not exist). Annas solution to the problem was an afternoon drink of tea, accompanied by a little food. While visiting the Duke of Rutland at Belvoir Castle in Leicestershire, she invited her female friends to partake, and so originated afternoon tea, or five oclock tea, as it is sometimes known.

Tea itself is a drink of Far Eastern origin. An expensive luxury when it first arrived from China in the seventeenth century, it became the height of fashion. In the eighteenth century, tea drinking gave opportunities to display fine porcelain teaware, and costly silver teapots. Many National Trust houses have examples of these. The Duchess of Lauderdales teapot at Ham House in Surrey is a precious and unusual Chinese porcelain thought to have been owned by Elizabeth Murray, Countess of Dysart and later Countess and Duchess of Lauderdale (16261698). Ickworth near Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, boasts a pair of spectacular George II teacaddies.

Tea gardens flourished at this time, their pleasant surroundings providing musical and other entertainments. Food, especially bread and butter, was offered alongside tea, but seems to have been secondary. The tax on tea was massively reduced in 1784 and tea drinking was taken up by all classes. The price of tea dropped again when the British established plantations in India and Ceylon in the mid-nineteenth century. Deep coloured, richly flavoured black teas taken with milk and sugar became the accustomed drink for many.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the idea of afternoon tea was firmly established. But, confusingly, tea was also a name for another late afternoon meal, one for busy people who came home from work hungry, ate and then relaxed or went out again. These meals were associated with regional and rural households, and also with poorer people. This type of tea would have been eaten in the Birmingham Back to Backs, and in farmhouses such as Townend at Troutbeck in the Lake District. Ham was a favourite item, as were eggs and various types of fish, especially those preserved by smoke. Winter teas included a hot dish; summer ones might run to salads and cold meats. When adopted by the wealthy metropolitan elite as an informal evening meal, this became known as high tea, to differentiate it from afternoon tea. Invitations to tea were laden with social nuances: one might end up faced with far more food than expected, or possibly with rather less.

Cricket, too, is inextricably associated with tea does any other sport routinely have a tea break?

Afternoon tea came to mean different things to different people. Children in wealthy households had their nursery or schoolroom tea of boiled eggs, bread and butter and other plain food. Families relaxed around a tea table, as depicted in Sir Winston Churchills painting Tea at Chartwell, 29th August 1927. In country houses, afternoon teas included heartier food for guests who had spent the day in the open air: scones, buns, fruit cakes. There were teas for gatherings to play fashionable games such as croquet or lawn tennis; late-nineteenth century cooks even created a special oblong cake, iced and decorated to resemble a tennis court. Cricket, too, is inextricably associated with tea does any other sport routinely have a tea break? And gentlemens clubs offered savoury food for members in need of late afternoon sustenance.

Items appeared on the table as ordained by date or personal taste, for Christmas, Sundays, birthdays. Localities, too, were noted for certain things: cream teas in the south-west of England, griddle-baked cakes and breads in Wales, and a rich selection of home-baking, such as parkin, at tea tables in the north. Other foods evoked nostalgia: muffins, touted round foggy winter London streets by vendors who rang bells to announce their presence; or the honey still for tea, which Rupert Brooke wove into his poem The Old Vicarage, Grantchester, written in 1912.

A chance to dress up and socialise, or the centre of a busy family routine, a pause in a work-loaded day, an excuse for a chat, a biscuit or more, snatched in a break or taken at leisure, tea means many things to many people. It has become a constant in British culture, much enjoyed by all.

Different Types of Tea

Tea, the drink, is made from the dried leaves of Camellia sinensis, an evergreen shrub first cultivated in subtropical regions of China. Buddhism took the plant and drink to Japan. Silk Road caravans took tea, often compressed as bricks, to Central Asia and Russia. European trade brought China tea to the west and then spread cultivation to countries such as India, Sri Lanka and Kenya. This dynamic history, combined with the tastes of many different cultures, has given rise to many types of tea, differentiated by leaf size, processing, region and various other factors.