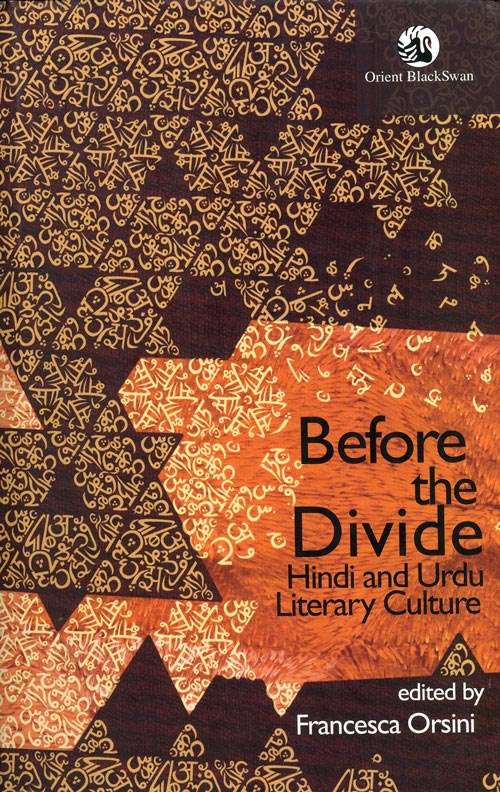

Before the Divide

For our entire range of books please use search strings "Orient BlackSwan", "Universities Press India" and "Permanent Black" in store.

Before the Divide

Hindi and Urdu Literary Culture

Edited by

FRANCESCA ORSINI

BEFORE THE DIVIDE

Orient Blackswan Private Limited

Registered Office

3-6-752 Himayatnagar, Hyderabad 500 029 (A.P.), INDIA

e-mail:

Other Offices

Bengaluru, Bhopal, Chennai, Guwahati,

Hyderabad, Jaipur, Kolkata, Lucknow, Mumbai,

New Delhi, Noida, Patna, Vijayawada

Francesca Orsini, 2010

First published 2010

This paperback edition 2011

Reprinted 2016

eISBN 978-81-250-5339-2

e-edition: First Published 2018

ePUB Conversion: .

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests write to the publisher.

Contents

- 1. Introduction

FRANCESCA ORSINI - 2. Rekhta: Poetry in Mixed Language

The Emergence of Khari Boli Literature in North India

IMRE BANGHA - 3. Riti and Register

Lexical Variation in Courtly Braj Bhasha Texts

ALLISON BUSCH - 4. Dialogism in a Medieval Genre

The Case of the Avadhi Epics

THOMAS DE BRUIJN - 5. Barahmasas in Hindi and Urdu

FRANCESCA ORSINI - 6. Sadarang, Adarang, Sabrang

Multi-coloured poetry in Hindustani Music

LALITA DU PERRON - 7. Looking Beyond Gul-o-bulbul

Observations on Marsiyas by Fazli and Sauda

CHRISTINA OESTERHELD - 8. Changing Literary Patterns in Eighteenth Century North India

Quranic Translations and the Development of Urdu Prose

MEHR AFSHAN FAROOQI - 9. Networks, Patrons, and Genres for Late BrajBhasha Poets

Ratnakar and Hariaudh

VALERIE RITTER

Acknowledgements

T he present volume is based on a workshop on Intermediary Genres in Hindi and Urdu which took place at the Faculty of Oriental Studies, at a panel on North Indian Literary Cultures Before the Divide organised by Professor Vasudha Dalmia of the University of California at Berkeley and myself at the 18 th European Conference on Modern South Asian Studies in Lund (Sweden) on 8 July 2005. I would like to thank the Smuts Fund (Cambridge) for funding the workshop, and Aditya Behl, Vasudha Dalmia and Samira sheikh for presenting papers which unfortunately could not be included in this volume. I would also like to thank Christopher Shackle, Shamsur Rahman Faruqi and Alok Rai for having encouraged my first forays into comparative Hindi-Urdu perspectives, and Vidya Rao for her particularly informed editing. The further I proceed along this path, the more I discover that R.S. McGregor had already been there, and this book is dedicated to his exemplary scholarship.

A Note on Transliteration

T ransliteration broadly follows R.S. McGregor in the Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary (Oxford University Press 1993) for Hindi. For Persian and Urdu words we have followed F. Steingass's A Comprehensive Persian-English Dictionary (various editions). We have used transliteration and diacritics only for the titles of works, quotations and unfamiliar words.

Introduction

Francesca Orsini

This essay has benefited from prolonged discussions with the participants in the workshop I organised on Intermediary Genres in Hindi and Urdu held in Cambridge (UK) on 15 September 2004 and the panel on North Indian Literary Cultures Before the Divide set up by Vasudha Dalmia and myself at the 18th European Conference on Modern South Asian Studies in Lund (Sweden) on 8 July 2005. I am also indebted to Daud Ali, Sudipta Kaviraj, Imre Bangha, Lalita du Perron, Samira Sheikh, Katherine Brown and Jessica Bath, who took part in a monthly reading group that commented on the essays in Sheldon Pollock 2002.

P recolonial India was a deeply multilingual society, with multiple traditions of knowledge and of literary production conducted in specific languages and a marked diglossia between classical languages and the vernacular. Yet the first histories of north Indian literatures, written during the colonial and nationalist periods and deeply involved in crystallising communities around language and cultural identity, rewrote literary history in terms of separate, single-language traditions as the competitive and teleological histories of ('Hindu') Hindi and (Muslim or secular) Urdu. As a consequence, these literary histories have been marked by appropriation, neglect and exclusion (Bangha in this volume). So far, the alternative to this fractious history of Hindi vs Urdu has been a narrative of composite culture, where selective syncretic traditions have been taken as definitive evidence that culture acted as a great cohesive force in the mixed Indo-Muslim polity. Both narratives have had to exclude much of literary production to prove their point.

The myth-making and exclusions that were involved in the construction of separate Hindu-Hindi and Muslim-Urdu literary traditions have been discussed at length by scholars in recent years, but an alternative to those flawed narratives is yet to emerge. This volume is the first attempt to rethink aspects of past Hindi and Urdu literary production outside the straitjacket of Hindi and Urdu literary histories. Some of the names and genres taken up by the individual authors will be familiar ones to students of Hindi and Urdu literary historyKeshavdas, Malik Muhammad Jayasi, Tulsi, Sauda, Upadhyay, Hariaudh, Braj Bhasha riti poetry, Avadhi epics and Urdu marsiyasothers, such as Vajid, Makhdoom Sarvarhalai or Maqsud, will be less familiar. But even the familiar inhabitants of the Hindi-Urdu literary terrain have been considered in an unfamiliar light. The authors move beyond the constraints of teleological narratives of Hindi and Urdu to explore the more spacious framework of north Indian literature. These reassessments of canonical texts and poets, and explorations of less familiar works and genres will prove to be crucial in reconstructing the multilingual and multi-dimensional literary world before the divide.

CRITICAL ISSUES

The first problem faced by nineteenth and early-twentieth century works on Hindi and Urdu linguistic and literary history, and in the debates that suffused the era of their composition, was that of language definition. The problem centred on the obvious differences in script and vocabulary in what seemed to be the same language, and also on the uncertainty surrounding the correct name of the language(s). John Borthwick Gilchrist, the influential writer of language textbooks, professor of Hindustani at Fort William College in Calcutta and, as a consequence of that position, patron of Hindi and Urdu writers, thought of it as a continuum, in which Hindi was the rustic, unPersianised bottom register, Persianised Urdu the top register, and Hindustani the preferred middle level. Gilchrist was also perhaps the first to identify language with script and religion, suggesting that Urdu and Hindustani, in the Persian script, were largely the language of north Indian Muslims, while Hindi in the Devanagari script was that of Hindus. As such, Gilchrist has been reviled in Hindi and Urdu literary histories as a classic proponent of the colonial policy of divide and rule. With the benefit of hindsight, however, we can see that he was both reacting to the social and cultural hierarchy of north India at a time in which Persianised speech was prized, and to the need of identifying the one common vernacular of Hindustan, i.e. north India. His identification of language with script was no doubt problematic and opened a veritable can of worms for both colonial officials and Indian intellectuals. As far as language definition is concerned, we believe, with Imre Bangha (this volume), that Hindi and Urdu are names for a multitude of north Indian vernacular dialects that from an outsiders point of view were simply called Hindavi (language of India), or Bhakha, (simply, the spoken language), to distinguish them either from Persian and Arabic or from Sanskrit and Prakrit.

Next page