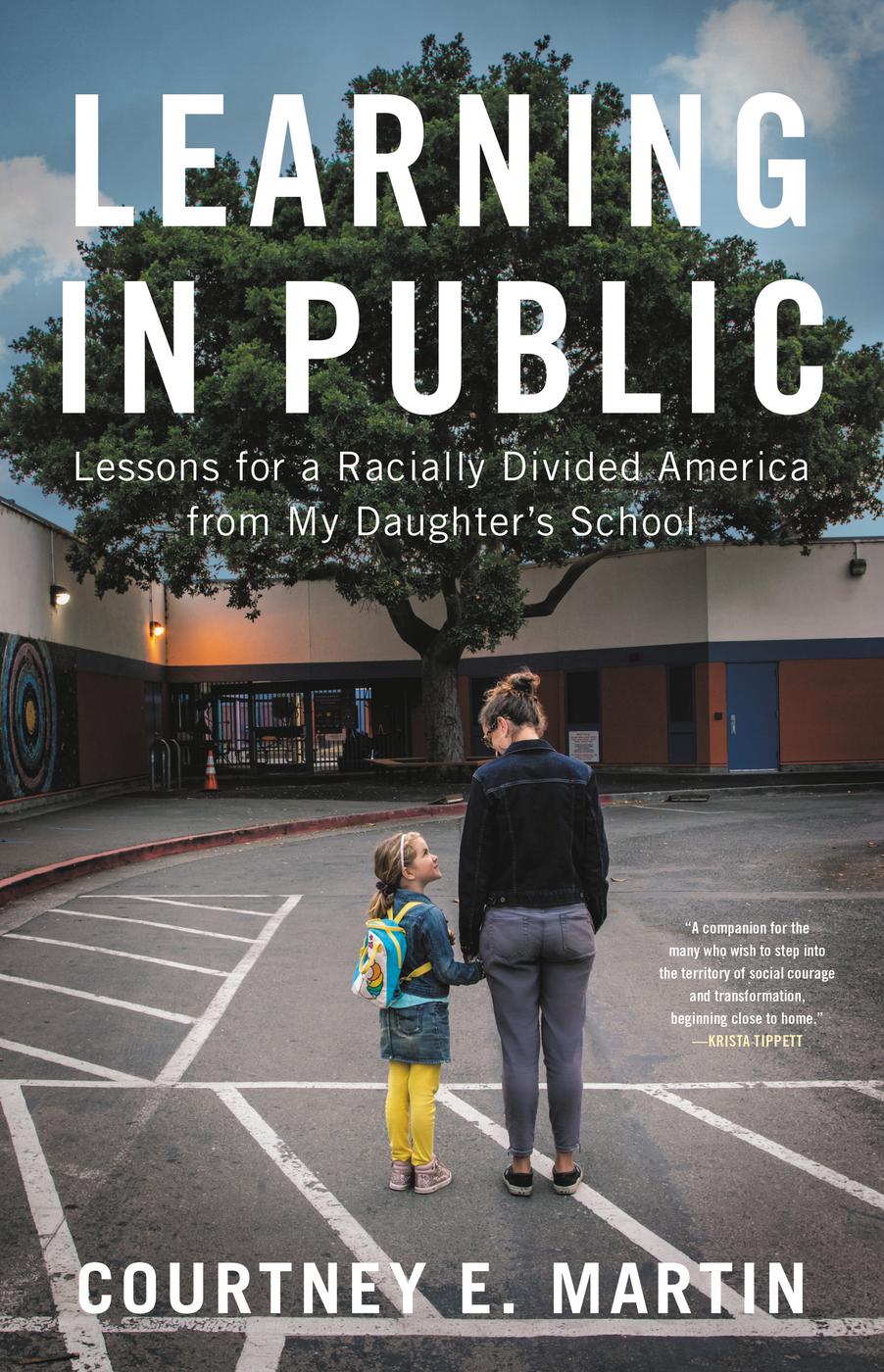

Courtney E. Martin - Learning in public lessons for a racially divided America from my daughters school

Here you can read online Courtney E. Martin - Learning in public lessons for a racially divided America from my daughters school full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Learning in public lessons for a racially divided America from my daughters school

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Learning in public lessons for a racially divided America from my daughters school: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Learning in public lessons for a racially divided America from my daughters school" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Learning in public lessons for a racially divided America from my daughters school — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Learning in public lessons for a racially divided America from my daughters school" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 2021 by Courtney Martin

Cover design and photograph by John Cary

Author photograph by Ryan Lash

Cover 2021 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

facebook.com/LittleBrownandCompany

twitter.com/LittleBrown

First ebook edition August 2021

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

1914 Emerson Elementary School class portrait () courtesy of Eileen Suzio

ISBN 978-0-316-42825-5

E3-20210630-NF-DA-ORI

For Maya, who is one of my greatest teachers already.

And for every kid who isnt her. Who deserves

just as much.

It is not a racial problem. Its a problem of whether or not youre willing to look at your life and be responsible for it, and then begin to change it.

That great western house I come from is one house, and I am one of the children of that house. Simply, I am the most despised child of that house. And it is because the American people are unable to face the fact that I am flesh of their flesh, bone of their bone, created by them. My blood, my fathers blood, is in that soil.

James Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro

How exactly do you cure bad blood?

Yaa Gyasi, 1932

W HEN I WAS A little girl, I went around and asked my neighbors for donations for the homeless. They handed me their loose change, and I listened as the metal hit the glass bottom of the jar satisfyingly.

I didnt actually know anyone who was experiencing homelessness. Or even anybody who was serving those who were. Where I live now, in Oakland, people who are unhoused are everywhereunder the highway a block away and even closer, under the stoop at the Glorious Kingdom Primitive Baptist Church across the street from our house. Once even in our black cherry Prius in our driveway, as happened when my husband, John, left it unlocked overnight.

John found an elderly Black man sleeping in the passenger seat, my daughters favorite book on CDMan on the Moonin his hand. John tried to wake him gently and asked him to get out. The guy looked up, clearly disoriented, and said, Ah, sorry, man. Is this mine or yours?

Ours, John said. Its ours, man.

Even at seven and eight and nine, I was confused about why some things were oursmy familys, my friends, my neighborhoodsand some werent. Even in that far less unequal time, there were dramatic differences between what Id heard called the haves and the have-nots. I was a have. I was born into a have familynot a trust-fund family, but a have family nonetheless.

I had a hunch that being a have had something to do with being White. And no one made much of an effort to explain it to me. We werent supposed to notice racenot others race, for sure, but not even our own. That would be racist.

I look back at that little White girlfrizzy hair, pile of friendship bracelets on her wrist, magenta high-top Chucks on her feetand I feel love and outrage. She was overcoming her shyness, circling the block in a misguided attempt at redistribution. From whom and to whom, she wasnt exactly sure. But she sensed something.

She needed truth. But she got loose change.

Unsure of what to do with the money, racked by guilt that she had asked for it but had no idea where to take it, she buried that jar of change in the dirt near her playhouse in the backyard.

This book is about the jar of good intentions that so many of us carry around these days. We set it on our bookshelves next to our copies of Ta-Nehisi Coates and Isabel Wilkerson. We put it by our tasteful succulent gardens next to our BLACK LIVES MATTER signs or on our nightstands. We stare at the ceiling in the dark, genuinely wondering why it feels so hard to be on the right side of history.

I left that sweet neighborhood in Colorado Springs when I was eighteen and went to Barnard College, in New York City. In new forms, I did lots of circling the block. I went to protest marches. I read slam poetry at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe. I made a short film about gentrification in Harlem. I joined the campus hip-hop club. I studied abroad in South Africa and lived in a township with a Black family. I graduated and moved to Brooklyn, as one does, and lived there for a decade. I wrote a book about activism.

The White moral life remained elusive. I was almost getting used to the idea that I would never have it, that it was a definitional impossibility. To have White skin and economic security in America was to be tangled up in the sin of what historian Aristotle Kallis calls the hierarchy of human life.

And then I became a mother.

And it was as if the universe dared me both to give up altogether on this quest for the White moral life, which felt like frivolous intellectual bullshit in the face of my kids real needs, and simultaneously to double down. The gift of adulthood is not a mortgage, I realized, but the freedom to pursue a moral life on your own terms, even if you are White, especially if you are White, and to let your children witness you trying.

This is the story of that trying.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

I HAVE AGONIZED OVER the ethics of telling this particular story at this particular time.

Journalists claim that they are objective, that once you interview a person, you have every right to use anything theyve said. Thats obviously bullshit.

Memoirists claim that they are subjective, that once youve witnessed or experienced something, you have every right to tell it your way. Thats obviously bullshit.

So here I am, somewhere in between, trying not to give you, my reader, or the people who got entangled in my decisions any bullshit.

I changed the names of all the kids except my own, and most adults, too. (Maya and Stella are already in the public record because the poor fools have a writer for a mom; dont worry, Im saving up for lots of therapy.) I kept the names of people who are public figures.

I showed sections of this manuscript to many of those described in these pages, which wasnt always easy. I tried to write no angels or villains, which wasnt always easy. I believe that our kids will do better when we, grown-ups, do the hard stuff of seeing one anothers humanity, even when we passionately disagree, and telling the truth about our own confusion and failures within education.

Ive capitalized ethnic designations throughout the manuscript, including White. Im following the lead of sociologist Eve L. Ewing, who writes that by not capitalizing White, we conspire with the myth that White people are normal, neutral, or without any race at all, while the rest of us are saddled with this unpleasant business of being racialized.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Learning in public lessons for a racially divided America from my daughters school»

Look at similar books to Learning in public lessons for a racially divided America from my daughters school. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Learning in public lessons for a racially divided America from my daughters school and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.