Copyright Page

30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA

Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier's Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (+44) 1865 843830, fax: (+44) 1865 853333, E-mail: permissions@elsevier.com. You may also complete your request online via the Elsevier homepage (http://www.elsevier.com), by selecting Support & Contact then Copyright and Permissions and then Obtaining Permissions.

Certain images and materials contained in this publication were reproduced with the permission of Autodesk, Inc., and/or its subsidiaries and/or affiliates 2008. All rights reserved.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, Elsevier prints its books on acid-free paper whenever possible.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Application submitted

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-0-240-81137-6

For information on all Focal Press publications visit our website at www.books.elsevier.com

09 10 11 12 13 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

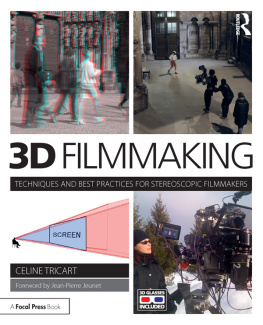

Preface Stereoscopic Technography

Ray Zone

In 2007 I was struggling with an assortment of 3D postproduction formats working with various digital geniuses to finish my independent short stereoscopic movie Slow Glass. The principle stereo cinematography had been completed in 2005 within a single week by Tom Koester and myself using a pair of JVC HD-10 digital cameras side-by-side on a bar. Now, almost two years later, the complex stereo blue screen compositing was slowly being finished. Terrific work had been completed by Brian Gardner, SFX supervisor Sean Isroelit, Tom Koester, co-producer and editor of the movie, and Bernard Mendiburu.

I had met Bernard in 2006 at the Stereoscopic Displays and Applications Conference held annually in San Jose, California. It was the centennial of the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco and Bernard had recently completed a wonderful short anaglyphic 3D documentary about the event combining historic stereoview card images and digital motion graphics. Subsequently I enlisted Bernards expertise to create an opening title sequence for Slow Glass and he did not disappoint. Within a week, and working in his spare time, Bernard created an amazing sequence, laying animated mirror-like 3D titles into the live action stereoscopic background plates.

Slow Glass would not have been finished without Bernard. The final shot, with complex blue screen composites, had been proving baffling to my geniuses. We called it the shot from hell. In this shot the actors walked across frame in front of a series of blue screen plates in the background and the 3D cameras panned with them as they moved. After the fact, I realized that all of the other blue screen shots in Slow Glass used a locked-down camera, except this final shot which came at the climax of the story. By shooting blue screen panels with panning cameras the complexity of the stereo comps had been logarithmically increased. It meant that every frame (or field) of the shot effectively became an individual special effect.

I see why everybody called in sick on this shot, Bernard told me when he saw the problem he had to solve. But all Bernard needed was a deadline, which I promptly gave him. Two weeks later the shot was finished. It worked perfectly, seamlessly, as a special effects shot should, by not calling attention to itself. Slow Glass went on to win two awards at 3D film festivals and is very well received today.

Bernard continued with his work to make stereoscopic contributions to the Disney/Pixar movie Meet the Robinsons, do 3D consultation with various software companies and to write this book. Up to the present day, stereo cinema has been such an intermittent format in theatrical exhibition, reappearing every few years, that no technological standards, or even consistent terminology, has evolved. This book marks a watershed in stereo cinema. As digital imaging fuels stereography at every level of image capture, generation, manipulation and display, the need for a fundamental pedagogy and toolset is daily evident. Bernard Mendiburu has opened up the stereoscopic toolbox and explained for us what is inside it. He has created a very useful overview of some of the tools and applications that exist today for the creation of digital stereoscopic motion pictures along with a clear explication of basic principles. And he has done this just in time for the desktop digital 3D revolution.

The digital 3D tools will continue to evolve along with the rapidly changing skillsets for motion pictures in general. Stereoscopic technologists, building or writing digital images on the z-axis, have always had to refashion existing tools for a perennially new application. No readymade tools for stereography have ever existed. But that is about to change, along with a fundamental understanding of how motion pictures can tell stories in a visual space that is elaborated both behind and in front of the screen.

For the creation of a technical primer on stereoscopic production, postproduction and exhibition, the ideal candidate was enlisted. He is a technological problem solver with a specific stereographic vision. This book will enable other workers, stereographers of the future, to share in that deep vision and participate in its enlargement in the coming years.

Ray Zone is an award-winning stereographer, 3D film-producer and writer who has published or produced over 130 3D comic books. Zone is the author of 3D Filmmakers: Conversations with Creators of Stereoscopic Motion Pictures (Scarecrow Press: 2005) and Stereoscopic Cinema and the Origins of 3-D Film; 18381952 (University Press of Kentucky: 2007).

Acknowledgments

Before I wrote this book, I never had a chance to understand why so many acknowledgments start by mentioning the authors family. Now I know. Thanks to Fabienne, Alienor and Lupin for supporting me and dealing with such a bad husband and daddy for the last two months. Chain writing is a painful experience, for the relatives too.

We are all Dwarfs on giants shoulders, and the giants that gave me a ride along my journey to the center of the 3D knowledge were, by order of appearance;

Bernard Tichit, franck verpillat*, Guy Rondy, Pierre Alio, Alain Derobe, Henry Clement, who collectively taught me all about video and 3D in Paris before I moved to new worlds.

All the 3D experts I met then and who shared their precious knowledge in interviews, conferences, or meetings; Rob Engle, Steve Schklair, Kommer Kleijn, Tim Sassoon, Michael Karagosian, David Seigle, Chris Yewdall, Brian Gardner, Yves Pupulin, Jeff Olm, Andrew Woods, Bruce Block, and, above all of them, the pioneer of modern stereography, Lenny Lipton.

Along with them, Im deeply indebted to Ray 3D Zone and Philip Captain 3D McNally for their help at learning the Hollywood 3D navigation rules.

I want to mention the members and employees of the movie professional associations that make sharing knowledge a reality. Here comes the acronyms soup; SMPTE, ASC, VES, CST, BKSTS, ISU, NAB, IEEE, SPIE... There would not be any magic without them.

I would like to express my appreciation to all the 3D professionals that provided me with illustrations and digital content for this book and its enclosed DVD.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, Elsevier prints its books on acid-free paper whenever possible.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, Elsevier prints its books on acid-free paper whenever possible.