CINEMA: From the Silent Screen to the Hollywood Blockbuster

Copyright Summersdale Publishers Ltd, 2015

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publishers.

Graham Tarrant has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Condition of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Summersdale Publishers Ltd

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

www.summersdale.com

eISBN: 978-1-78372-511-3

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Summersdale books are available to corporations, professional associations and other organisations. For details contact Nicky Douglas by telephone: +44 (0) 1243 756902, fax: +44 (0) 1243 786300 or email: nicky@summersdale.com.

For my three leading ladies: Abigail, Francesca and Rose.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

On my first few visits to the cinema I was six or seven at the time and accompanied by my parents nervous anticipation caused me to throw up, with the result that I never managed to see a film all the way through until I was into double figures. I like to think it was an early airing of my critical faculties, as Ive walked out of a few movies since, but in truth it was simply the excitement of being in that magical environment, an element of which has never left me. By the time I hit my teens I was an avid movie fan and once spent a wet day (and night) in London sitting through the programmes at five different cinemas back to back.

Nowadays these former picture palaces are just one of the viewing options open to the moviegoer. Films can be watched on planes, trains and in cars (providing somebody else is driving); on televisions, laptops, iPads and mobile phones though surely only those desperate for a cinematic fix resort to the latter. The point is that for many people viewing a film has become a solitary experience, like listening to music or reading a book. But if watching movies isnt quite the communal event that it used to be, it is certainly no less miraculous.

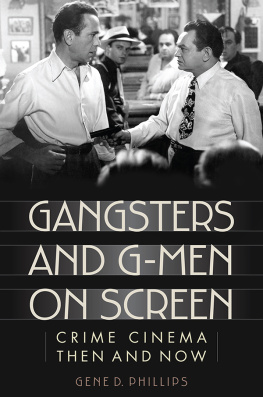

At the throat-lumping climax of Casablanca , Humphrey Bogart reassures a tearful Ingrid Bergman that well always have Paris. More importantly, for those of us mistily watching the scene for the umpteenth time, is that well always have Casablanca and much more besides. Thanks to the miracle of film (and the supporting technology of DVDs and downloads) we shall always have the curvaceous charms of Marilyn Monroe and the rebellious spirit of James Dean; a pigtailed Judy Garland will always be waiting for us on the Yellow Brick Road and John Wayne will forever be doing what a mans got to do. We can dip at random into half a century of Jack Nicholson or Michael Caine, or let the force of Star Wars be with us over and over again. Favourite movies from Brief Encounter to The Hunger Games can be digitally stored in a personal archive, to be viewed whenever the mood takes us.

Film-making is a protracted, costly and often tedious affair, with longueurs that sometimes drive actors in particular to distraction (having spent a year on the west coast of Ireland shooting David Leans 1969 epic Ryans Daughter , actor Leo McKern commented I dont like to be paid 500 a week for sitting down and playing Scrabble.). It can be a physically hazardous occupation with actors and, more predictably, stunt personnel being frequent casualties, along with cameramen and even directors. The financial rewards of course can be breathtaking but there are also damaging losses, to reputations as well as to bank balances. None of this need worry the movie fan, however, who can just sit back and enjoy the finished product or not, as the case may be.

Lets Go to the Movies sing Daddy Warbucks and the young eponymous heroine of the 1982 musical Annie . Its a fine idea and the underlying message of this book. Cinema has created a galaxy of stars (and superstars) since its tentative beginnings a hundred or so years ago. Countless directors, writers, composers, artists, cameramen and other technicians have displayed their distinguished talents on the big screen. Only a few can be mentioned in this brief celebration of cinema, though hopefully enough to send moviegoers down some hitherto unfamiliar paths.

In the year between writing this book and its publication thousands of new films will have been produced (close to 600 in Hollywood alone, though that is only half the annual output of Indias vast movie industry). Not all of them will get distribution or be worth watching, but plenty will. Some may in time become classics, others will certainly warrant a second or third viewing. Happily, our appetite for cinema shows little sign of diminishing, with a new crop of movies to feast on every year.

CHAPTER 1

THE FLICKERING IMAGE

Of all the arts, the cinema is the most important for us.

V LADIMIR I LYICH L ENIN

The American Thomas Alva Edison has harvested most of the credit for inventing moving pictures, though in fact it was a collaborative effort involving many European pioneers over a period of half a century or more. Indeed the process might be said to have started with the development of the magic lantern in the seventeenth century.

In 1876, Edison had come up with the phonograph. Now, with his brilliant assistant W. K. Laurie Dickson alongside (some film historians believe the bulk of the credit should indeed go to Dickson), he threw himself into the task of inventing a visual equivalent, a mechanical device that would project moving pictures.

The result of their combined endeavours, the kinetoscope, went on display in 1894 and took America by storm. The breakthrough had come a few years earlier with the development by Eastman Kodak of flexible celluloid film, the use of which was crucial to Edisons design. By looking through the peephole of the machine the viewer could see images of people or things in motion. It was jerky and grainy, but it was a moving picture.

The zoetrope

In 1834 a British mathematician, William George Horner, created the zoetrope (from the Greek zoe , meaning life, and tropos , turning). Horners popular optical toy was in the form of an open-topped cylinder or drum, with a number of equally spaced vertical slits around the side. On the inner surface of the drum was a sequence of pictures. As the drum revolved the viewer peered through the slits at the pictures opposite, the rotating images giving the illusion of moving action. When Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas set up their Californian film company in 1969, they called it American Zoetrope.

Moving pictures

Hundreds of kinetoscopes flooded onto the market and were set up in penny arcades and peep-show parlours. The visual content, produced in Edisons own studio, included erotic dances, slapstick routines and boxing bouts. With people queuing up to view at a penny a pop, the money poured in, and Edison the businessman was at first content to leave it at that, believing that to project his movies onto a larger screen for an audience to see together would simply reduce the market. However, as others moved in to capitalise on his invention and projection equipment improved, Edison changed tactics and sanctioned the screening of his material, initially in vaudeville theatres where for a while the new attraction eclipsed even the most celebrated stage acts.