Copyright 2018 by Summersdale Publishers Ltd

First Skyhorse Publishing edition 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Graham Tarrant has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover images Malchev (tall book stack), Kuroksta (chair), Don Pablo (open book), Isovector (glasses), vectorgirl (small book stack)/Shutterstock.com

Open book icon on pp.

Book stack icon on pp.

Cover design by Qualcom

Cover illustration credit by iStockphoto

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-4157-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-4158-4

Printed in the United States of America

For Abigail, Francesca and Rose.

And for Ricardo Oliveira Costa.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Books are companions for life and ideal companions at that. They are constantly there when you need them, uncomplaining if cast aside, always ready to continue the relationship wherever it left off. You can take a book (paper or screen) on a plane or train, to the beach or to a hospital appointment. Sitting alone in a cafe or restaurant becomes a less solitary experience if you are accompanied by a book.

Books, at their best, can nourish the mind and liberate the spirit. They can comfort, humour, thrill, intrigue and arouse. Reading can be a leisurely affair, allowing time for reflection or to retrace ones steps in an intricate narrative. It can be a white-knuckle ride, pitching the reader, wide-eyed and dry-mouthed, into the on-rushing story. And few experiences are more rewarding than reading to children, especially a much-loved book from ones own early years.

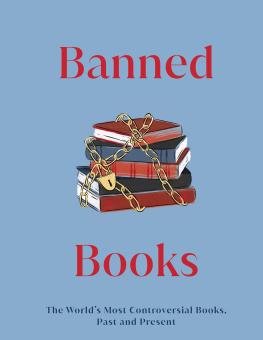

It is hard to imagine a world without books, though some dystopian novels have painted a grim picture of such an eventuality. Even in the real world the decline, if not the actual demise, of the book has been confidently forecast from time to time. Cinema, television, video games, the internet and social media have all been cited as threats to its survival. Yet the latest market trends (in the UK at any rate) show the book to be in rude health, with sales of the traditional printed form more buoyant than those of the electronic upstart. To those of us with a love of books, this comes as no surprise.

Authors vary as much as the books they write, though they all share the daunting challenge of getting words on paper. Some have led lives as unlikely and remarkable as any work of fiction. Many have struggled with poverty, prejudice, addiction and the dreaded writers block. Others have found it necessary (and financially fruitful) to channel their prolific outpourings through a pipework of pseudonyms.

This is a light-hearted book about books and the people who write them. It has stories, characters and plots, which are all the more compelling for being true. There are books and writers to discover, or perhaps to revisit. Readers with literary aspirations of their own can pick through the mixed experiences of those who have come before. All this and more will hopefully keep the pages turning. That is as much as any author can ask.

THE COMING OF THE BOOK

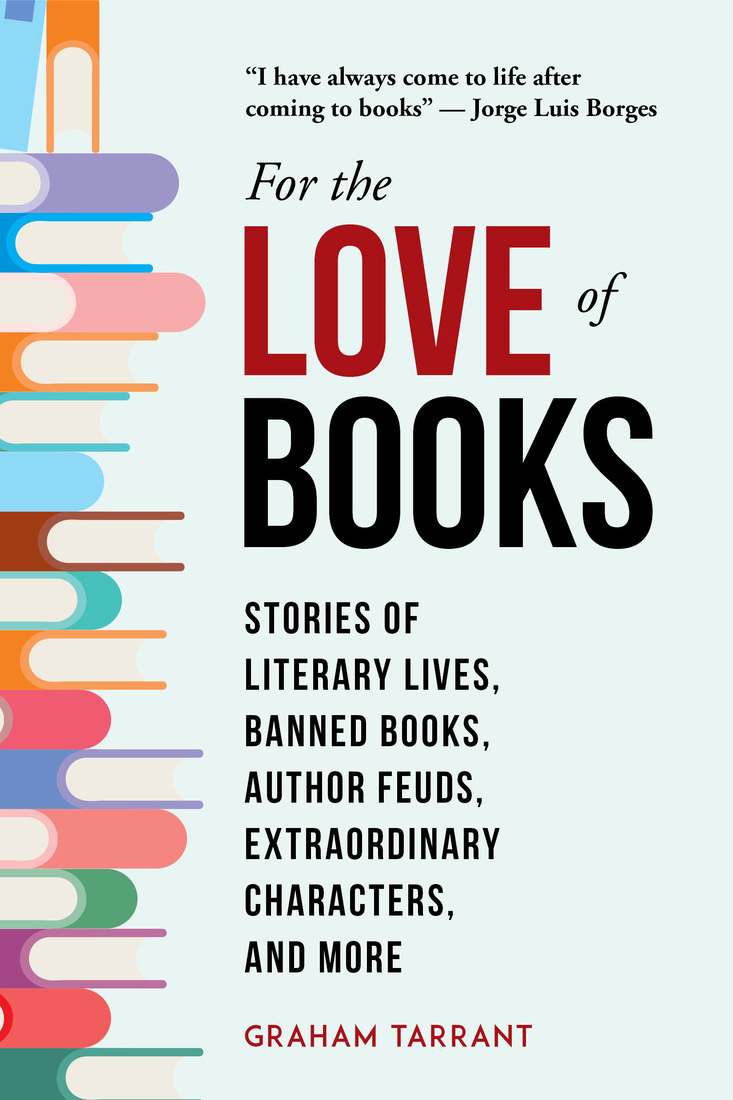

I have always come to

I have always come to

life after coming to books.

JORGE LUIS BORGES (18991986)

Before the invention of writing, the spread of literature was by word of mouth. Folk tales, legends and epic sagas were transmitted in spoken form, often by itinerant storytellers. Many were embellished over centuries. Some were later written down and are still read today, such as the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh ( c. 2000 BC ), said to be the oldest story in existence, and the Greek sagas of The Iliad and The Odyssey ( c. 750 BC ), attributed to the allegedly blind poet Homer but probably a combined effort involving other bards.

THE BOOK TAKES SHAPE

Writing is generally credited to the ancient civilisation of Sumer, later known as southern Mesopotamia, round about 3000 BC . The book began to take shape in many different ways. The Sumerians themselves wrote on clay tablets, while in ancient China, the earliest forms were made from wood or bamboo leaves bound with cord. In Egypt and Greece, the written word was committed to papyrus scrolls, which were unrolled to reveal their contents. The Romans, in the first century AD , moved things on with the introduction of the codex: manuscripts of vellum or parchment, stacked sequentially and attached along one edge so that pages could be turned.

ITS A FACT!

The word book is derived from the Old English bc , originally a document or charter. It is related to the Dutch boek and German Buch . Another associated word is beech, the wood on which ancient runes were often carved.

The Chinese chipped in with two seismic inventions, that of paper and printing. Paper suitable for writing purposes was first manufactured in AD 105. Woodblock printing (the characters and images carved onto wood before being inked and applied to paper) came a century or two later. The worlds oldest-known printed book, The Diamond Sutra a sacred Buddhist text, written in Chinese and dated AD 868 was produced using this technique.

The next significant development, in the eleventh century and again courtesy of the Chinese, was the invention of moveable type. Instead of cumbersome wood-carving, printers used individual characters made from fired clay to create an image or body of text. As a result, books could be created faster and in greater quantities.

LIBRARY OF ALEXANDRIA

Founded in the third century BC and dedicated to the Muses (in Greek mythology, the nine goddesses of the arts), this was the most famous library in the ancient world. The legendary book depository was created by Ptolemy I Soter ( c. 367282 BC ), a former Macedonian general who became king of Egypt. For close to 300 years under the Ptolemaic Dynasty, Alexandria would be a centre of Greek culture.

The contents of the library consisted mainly of papyrus scrolls, several of which might comprise a single piece of work. Estimates of the total number of books housed vary between 400,000 and 700,000. Some of the works were original, others painstakingly copied by hand. The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384322 BC ) and the playwrights Aeschylus (524456 BC ), Sophocles ( c. 496406 BC ) and Euripides (480406 BC ) were among those whose works lined the shelves. The acquisition of books was relentless, and at almost any price. Ships entering the harbour were often searched, any books found on-board being confiscated for copying. If a book was of particular value or interest, the library would hang on to the original version and hand back a copy.

Next page

I have always come to

I have always come to