Page List

First published in 2021 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

Katherine Brett 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 958 7

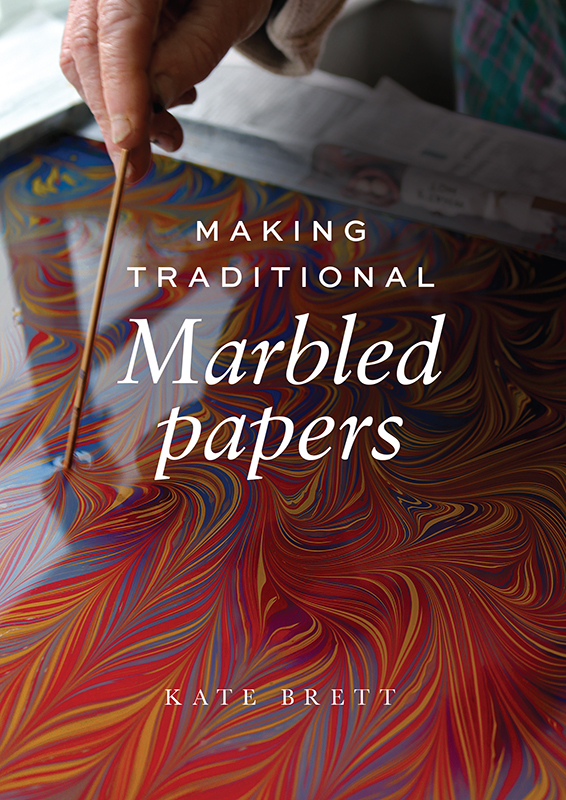

Cover design: Sergey Tsvetkov

Photographs and illustrations: Blythe Brett

Acknowledgements

With many thanks to Nick Abrams, J. & J. Jeffery (bookbinders and paper pattern makers extraordinaire), Jake Benson, Kubilay Diner, Barry Brignall, Chris and Sarah Shaw, Ola Snden University of Bergen Library, Asa Henningsson Uppsala University Library, Linda Sorensen National Library of Sweden, Peter Wrmling, The Schmoller Collection, Anne Ullmann, Anil Goutam Rahis Papers, Solveig Stone, William McCracken, Richard Renouf, Beth Scanlon, Rosi de Ruig, and enormous thanks to my daughter Blythe, without whom I could not have put this book together.

INTRODUCTION

The thousand-year-old craft of marbling is alive and well, and it can be practised and appreciated by everyone, from children to professionals. There are various different methods of marbling, and it can be used in commercial trade, as the basis for artistic or academic study, or as a source of relaxation, therapy or fun.

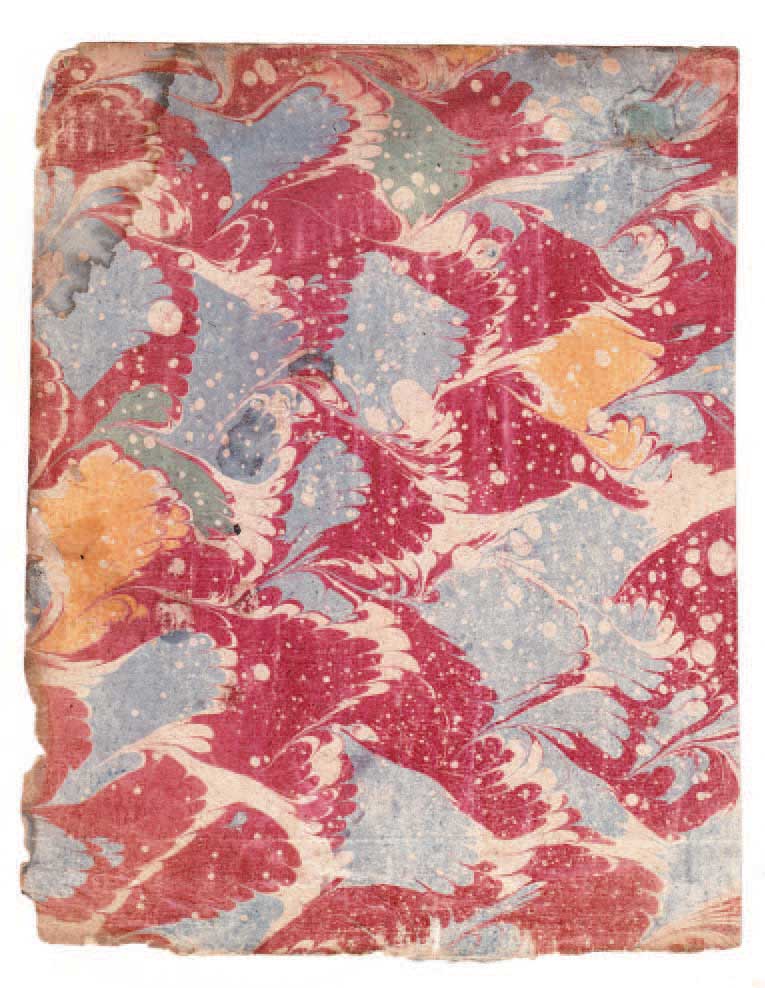

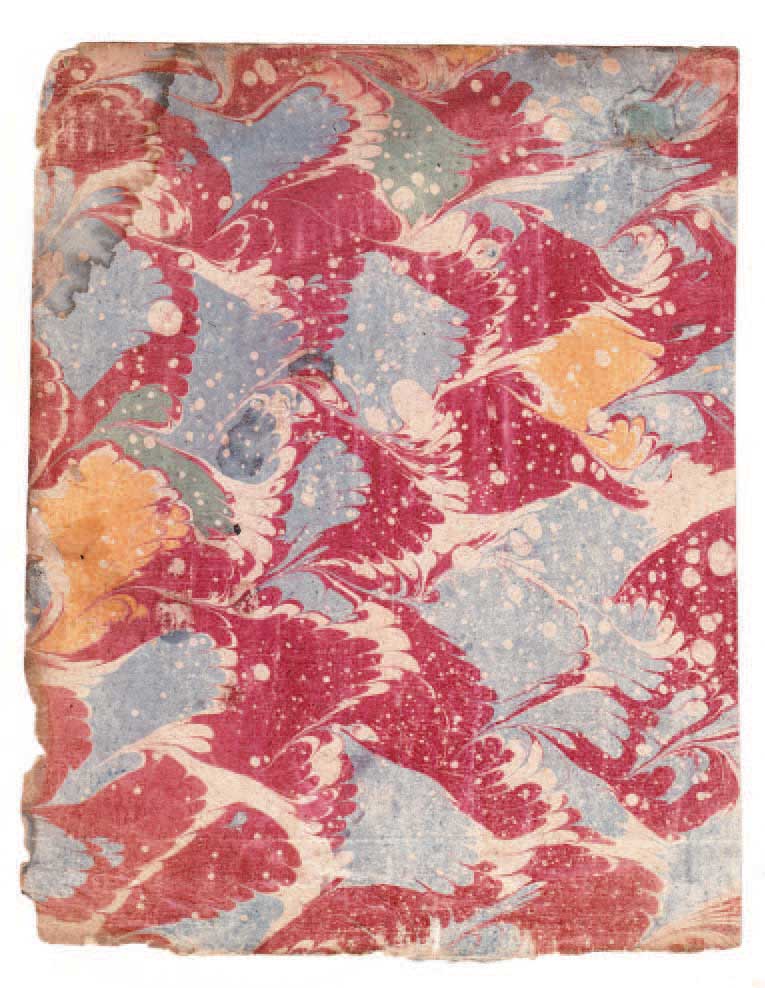

Endpapers from early eighteenth-century books, showing the colours generally used in early marbling Indigo, Red Lake, Yellow Ochre and Lamp Black.

The Placard a very early pattern first created and used for book decoration in France between 1680 and 1740.

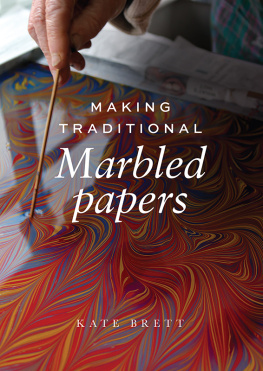

Marbling is the name given to the creation of designs and patterns on the surface of a liquid, which is then transferred onto paper or other materials. This book will concentrate on marbling paper in the traditional way, which is an old process using water-based paints floating on a jelly or size. In this book I will particularly concentrate on the history and making of marbled papers in Britain, and on the traditional patterns that are still popular today.

A Brief History of Marbled Paper

Historically there are two basic marbling traditions.

The first was found in Japan as early as 1118, and known as suminagashi. This was made by floating drops of ink on water, then a sheet of paper was placed on top and the design was transferred. These papers, apart from being works of art in their own right, were used as a background on which to do calligraphy and also as a unique security measure for documents. Suminagashi represents marbling in its initial and simplest form.

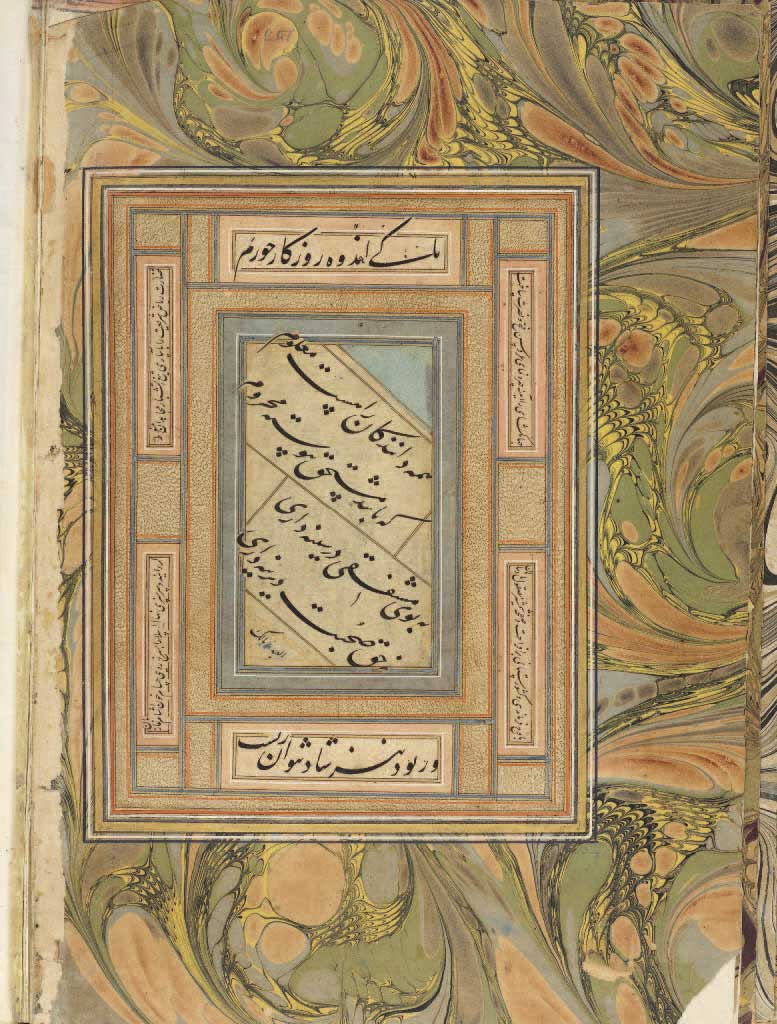

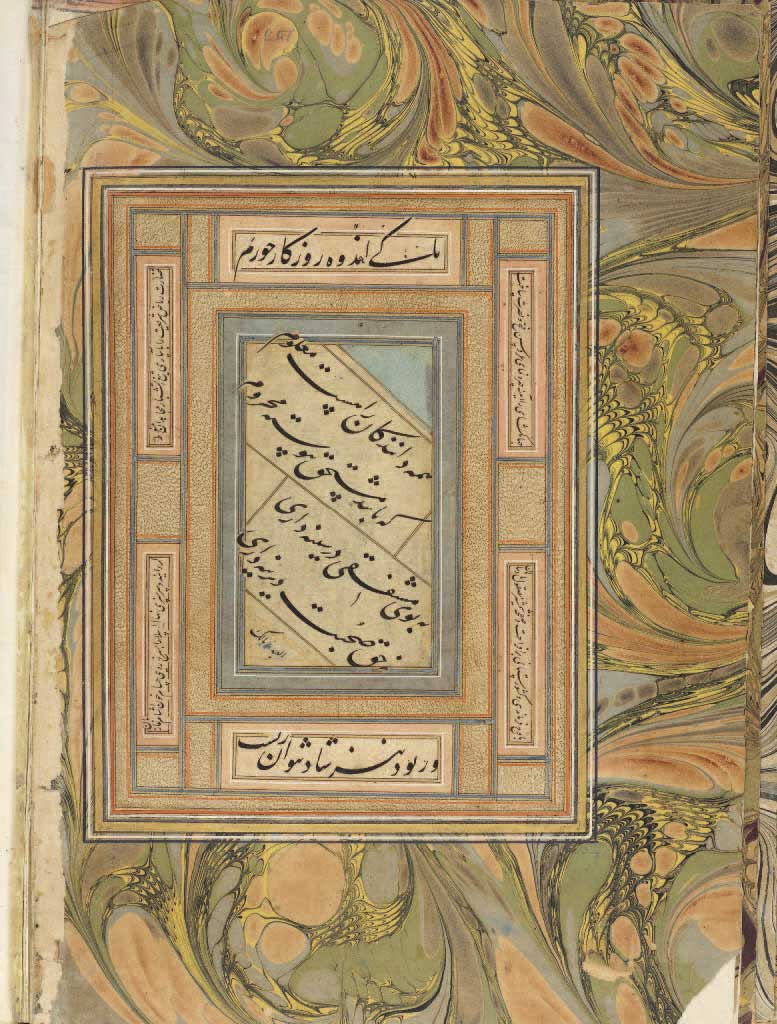

By the 1400s, the Iranian lite began migrating to the Deccan plateau of south India, where a new marbling tradition began. Lured to the region for many reasons, these poets, traders, statesmen and artists of all kinds left an indelible mark on the Islamic sultanate that ruled the Deccan until the late seventeenth century. By 1600, one Muhammad Tahir, an enigmatic Persian artist and migr to India, was producing highly innovative marbled papers with intricately worked combed designs, used as borders for paintings or calligraphy (from Iran and the Deccan, Jake Benson, Indiana University Press, 2020). Deccan marbled drawings are occasionally illustrated, and an elaborate technique was developed using stencils outlined in gold, with painted faces added to complete the work. The marbling on these documents and figures is of a very high standard. These methods of marbling quickly spread from India to greater Iran and the Ottoman Empire.

A page from Qitat-i Khushkhatt a Persian album of calligraphy and marbled paper, with marbled papers by Muhammad Tahir, c.1600. (Photo: University of Edinburgh Library)

Evidence demonstrates that Turkey was the conduit by which marbling arrived in Western Europe. A fledgling decorative paper industry emerged among professional stationers in Istanbul during the mid-to late sixteenth century. As early as the 1570s European travellers to Istanbul purchased these colourful Turkish papers and had them bound into small friendship albums (alba amicorum). These early sixteenth-century papers had rudimentary stylized drop-motifs and primitive spot patterns and have a distinctive smell of curry because the size that was involved in their making was extracted from fenugreek seed. Some of the albums containing old marbled papers still carry this distinctive smell because fenugreek was used as a size on which to float the colours in India and also in Persia.

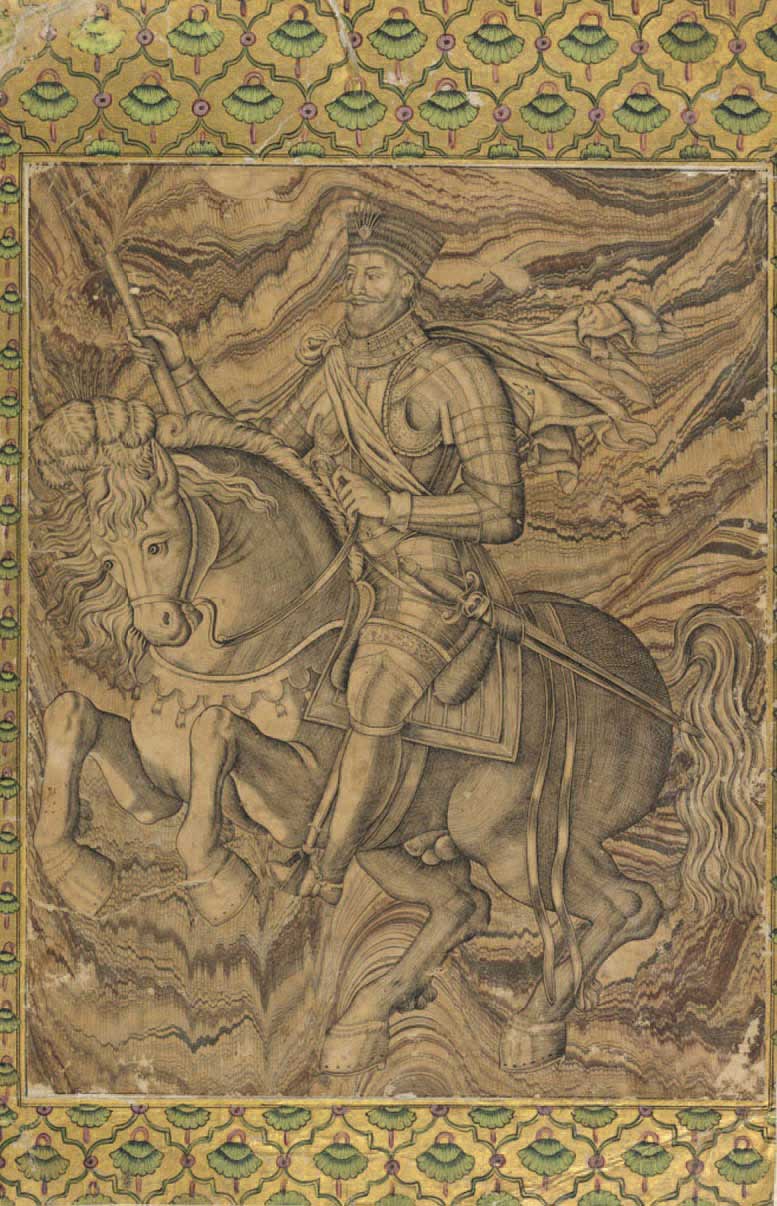

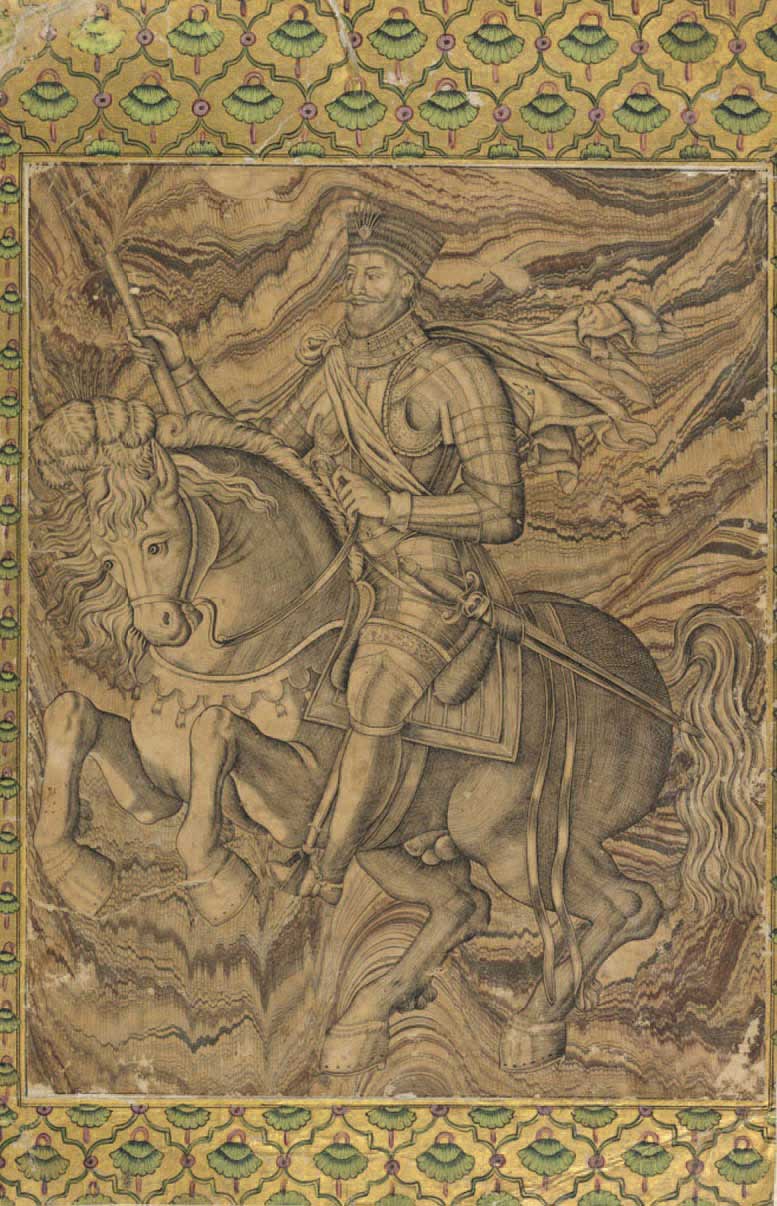

Pen copy of the engraved portrait of the Earl of Northampton, c.1599, ascribed to T. Cockson. Pen and black ink on marbled paper. (Photo: Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge)

The earliest English description of marbled paper appears in 1615. George Sandys, who travelled in the Islamic world in 1610, wrote that they curiously fleek their paper, which is thicke; much of it being coloured and dappled like chamolet; done by a tricke they have in dipping them in the water.

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries marbled patterns became more controlled and the water on which the paints were floated was thickened. Natural thickeners were used to create the jelly or size on which the paint patterns were created. Size ingredients such as gum tragacanth became common later.

Marbled papers became a popular covering material not only for book covers and endpapers, but also for lining chests, drawers and bookshelves. The marbling of the edges of books was also a European adaptation of the art. The golden age of marbling in France and Germany ran from the 1680s until the 1730s/40s. The patterns produced there were rather beautiful and formal in their design.

By the middle of the seventeenth century marbled paper had made its way to Britain. Goods were imported from Germany through Holland the Dutch acted as commission agents, buying and selling goods that they reexported. Marbled paper was first brought into England as wrappings on parcels of toys from Holland in order to avoid the heavy English duty tax on paper. Hence some of the earliest papers found in Britain are known as Old Dutch. The art did not fully blossom in Britain until the 1770s, and from then on it had a strong and energetic existence for the next fifty to seventy-five years.