As a medieval historian by training my PhD was in thirteenth-century state finance and fiscal history Ive always been drawn to this period, primarily writing about the financial institutions that were created to support the continental ambitions of Henry II and his family. However, my professional career has taken me down some unusual and interesting paths, including various TV projects researching stories about celebrity ancestors. These have demonstrated the fundamental importance of families throughout history. Nowhere do these two worlds collide with the same dramatic impact as in the late twelfth and early thirteenth century.

This book, though, would never have happened without the help of some special people. First, a thank you to Dan Jones, who kindly invited me to the launch party of his brilliant book The Hollow Crown in 2014 where I met his editor Walter Donohue, to whom the second vote of thanks must go for showing faith in my pitch for a new take on this period, and persuading his colleagues at Faber to agree that this was a story worth re-telling. As always, my agent Heather Holden Brown and her team turned the idea into a reality. Yet, the deepest debt of gratitude is reserved till last for my family of restless children, Elizabeth, Charlotte, Chloe, Alice and Matilda (who at three years old is already displaying some of the haughty confidence displayed by her namesake the Empress), and, above all, my wife Lydia an inspiration, always.

There was an eagle painted, and four young ones of the eagle perched upon it, one on each wing, and a third upon its back tearing at the parent with talons and beaks, the fourth, no smaller than the others, sitting upon its neck and awaiting the moment to peck out its parents eyes. When some of the Kings close friends asked him the meaning of the picture, he said, The four young ones of the eagle are my four sons, who will not cease persecuting me even unto death. And the youngest, whom I now embrace with such tender affection, will someday afflict me more grievously and more perilously than all the others.

GERALD OF WALES

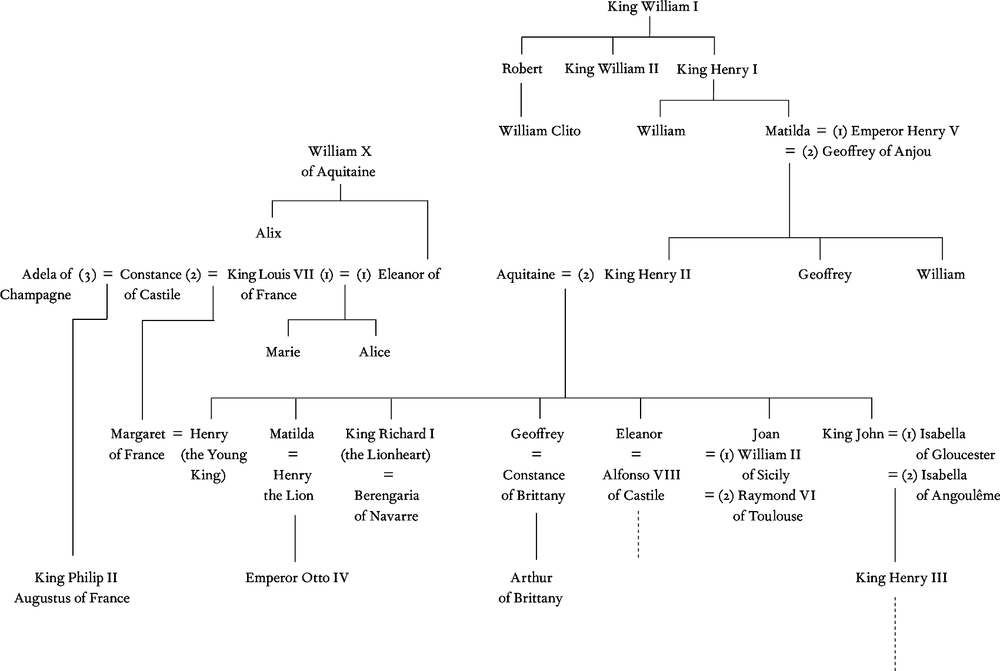

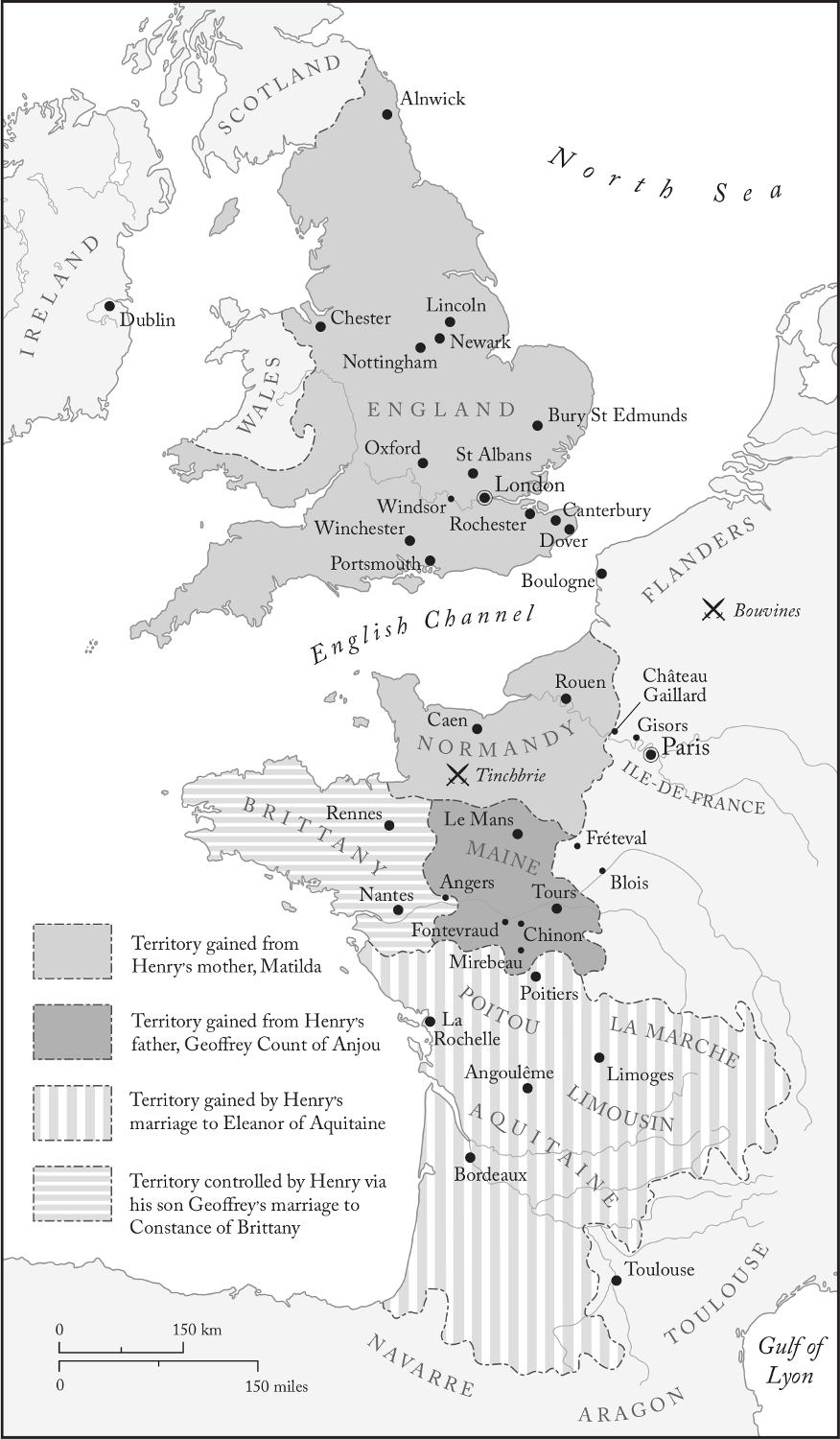

Thus wrote the twelfth-century chronicler Gerald of Wales, and his ominous choice of words proved to be tragically prophetic. On 4 July 1189, King Henry II of England, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Count of Anjou, Lord of Ireland, and possibly the most powerful man in western Europe, was forced to make a humiliating peace settlement with his eldest surviving son, Richard, who had rebelled against him with the support of Henrys arch-rival, King Philip Augustus of France. Even as he exchanged the kiss of peace on a hot, dusty summers day, Henry whispered into his sons ear, God grant I die not before I have worthily revenged myself on you! In his heyday this would have been no idle threat indeed, the cause of the dispute was Richards real fear that he was about to be disinherited. However, Henry was old, ill and wounded, suffering the effects of blood poisoning brought about by an injured heel, and wearily retired to nearby Chinon castle demanding to know who else formed part of the revolt against his rule. A messenger rode to the castle the next morning, with the news that Henrys youngest and favourite son, John, had joined the rebels. Henrys resolve was shattered; in despair he turned his face to the wall muttering: Now let everything go as it will; I care no longer for myself or anything else in the world. He quickly lapsed into delirium and died the following day in the castle chapel, his last words reputed to be: Shame, shame on a conquered king.

The internecine family struggle between Henry II and his children, played out on a stage that stretched from the foothills of the Pyrenees to the Scottish borders, remains a compelling, tragic drama in its own right a cross between Game of Thrones and The Sopranos, with plot twists that would stretch credulity had they been scripted for television. The sixty-two years between Henrys accession in 1154 and the death of John in 1216 included the murder of the archbishop of Canterbury; holy war in the Middle East; the capture and ransom of a king; the loss of a vast swathe of continental possessions, a disaster on the scale of the American War of Independence; and Englands subsequent descent into open revolt, civil war and invasion by French forces. Legend stated that the house of Anjou was descended from the devil, and at times it is hard to describe the behaviour of Henrys family as anything other than diabolical as father fought sons, brother betrayed brother, spouses plotted against one another, and a nephew was murdered by his uncles bare hands. These were violent and ruthless people, even by the standards of an era not known for its gentleness. Yet it would also be a mistake to paint a picture of Henry II and his family in such crude, simplistic terms, as they possessed a broad spectrum of characteristics that made them highly formidable and, after all these years, still intriguing to a modern audience. They embodied a fierce intelligence and military prowess coupled with an administrative flair that often bordered on genius, as the restless kings raced around their territories to dispense justice, collect revenue and ensure their authority was not challenged regularly displaying a warmth, humour and even kindness that shone through in their frequent interactions with European peers, leading magnates, and the members of the lesser ranks of society who appeared before their itinerant court.

Equally, it would be wrong to dismiss events from eight centuries ago as an irrelevant if bloody footnote in history textbooks, spanning the period between the Norman Conquest and Magna Carta, as part of an abridged national curriculum: a slice of history when England emerged from the rule of French aristocrats more interested in foreign affairs to develop its own cultural identity, as Victorian historians such as Macaulay and Stubbs would have us believe. In fact, if we are to understand some of the conventions that shape modern British society, we need to revisit the social, constitutional and legal developments that the Angevin kings introduced in England. These arose partly out of necessity whilst they were away ruling their vast continental territories, but also were possible because the foundations for centralised government were already in place, thanks to the unification of England under Alfred and his successors in the tenth century. Unlike most other territories under Henry IIs control or indeed most other European states of the time England had developed central administrative practices based on a cascading national, regional and local infrastructure rather than a network of semi-independent lordships that relied on castles to secure autonomous power. The collapse into anarchy and private warfare under King Stephen (113554), with a rash of unauthorised castles springing up as royal authority vanished, demonstrated a nightmarish alternative version of England more akin to continental practice that Henry was determined to avoid.

The twelfth century saw the birth of many of Englands governmental institutions such as the exchequer, the rise of powerful officers of state like the lord chancellor, the emergence of a judicial system dominated by the crown, and the strict enforcement of a class system based on concepts of overlordship and service, all soon to be counterbalanced by the articulation in Magna Carta that no man was above the rule of law the cornerstone of natural justice still in force on the British Parliaments statute book today. These innovations are a legacy of Henry II and his sons whether their actions were deliberate or inadvertent. Nevertheless, in one sense Macaulay and Stubbs had a point, as it would be a mistake to think of the story of the restless kings solely in terms of English history. Henry II and his children were culturally European first and foremost, as their dynastic name suggests: if their possession of England gave them their royal dignity and elevated them to the top table of European power brokers, their hearts and minds belonged to their family lands on the continent, centred on Anjou in the mid west of France.