ALSO BY MATT LEE AND TED LEE

The Lee Bros. Southern Cookbook

The Lee Bros. Simple Fresh Southern

Copyright 2013 by Matt Lee and Ted Lee

Photographs copyright 2013 by Squire Fox except as indicated

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.clarksonpotter.com

CLARKSON POTTER is a trademark and POTTER with colophon is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lee, Matt.

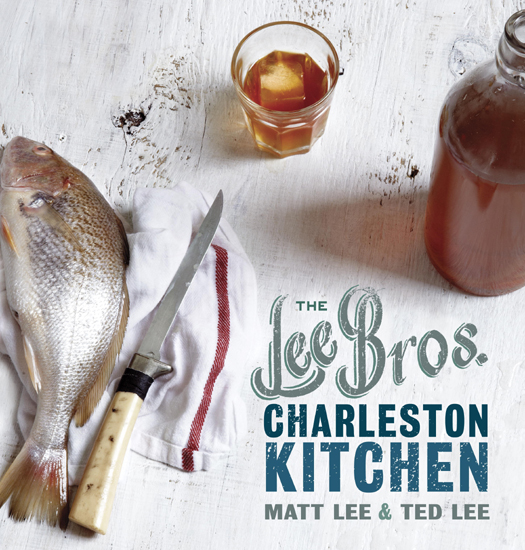

The Lee Bros. Charleston kitchen / Matt Lee and Ted Lee. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes index.

1. Cooking, AmericanSouthern style. 2. CookingSouth

CarolinaCharleston. I. Lee, Ted. II. Title.

III. Title: Lee Brothers Charleston kitchen.

TX715.2.S68L4448 2012

641.5975dc23 2012013331

ISBN 978-0-307-88973-7

eISBN: 978-0-7704-3395-6

Photographs copyright 2013 Matt Lee and Ted Lee.

Photographs reprinted with permission

Map illustrations copyright 2013 by David Cain

Design by Stephanie Huntwork

Jacket design by Stephanie Huntwork

Jacket photography by Squire Fox

v3.1

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO OUR FAMILIES

CONTENTS

WELCOME!

WE ARE WALKING THROUGH NEAT ROWS OF COLLARD GREENS AT Joseph Fields Farm on Johns Island, thirteen miles south of downtown Charleston. Its just after 8:00 A.M. on an early March morning and the sun struggles against a low fog. Carrying wooden produce crates, we step across furrows of sandy dirt, leaving deep footprints as we follow behind farmer Joseph Fields and a farm manager. They cut whole heads of collards at the stalk with pocket knives and toss heavy bunches of greens into our crates.

Were hosting an oyster roast tonight, an impromptu gathering at our test kitchen on Wentworth Street, to welcome a former roommate who popped into town on business. We called some people yesterday, and they called some more, and theres got to be nearly forty of us now. (By party time we may be fifty.) No problem: oysters for that many is easy in Charleston. Our beloved Crassostrea virginica, earthy and generously salty, grow one upon another in clustered, torch-shaped forms in intertidal marshes of the coastal plain. A single cluster may have four or eight or more bantam-sized oysters clinging to it. These arent white-tablecloth singles, but they are the correct, perfect oyster for the outdoor roast, where guests crowd a plywood table as shovelfuls come off the fire, and then set about the task of breaking the clusters apart, shucking around to find all the treasure within. Seafood markets in the area sell these oysters in white woven bushel bagsa single bushel might hold three hundred oysters but cost less than thirty dollars.

By far the larger challenge for this many people is the collards. Youve got to offer some sustenance other than bivalves and beer at an oyster roastsomething you learn from growing up here (and also that a good-sized bunch of collards might only feed two people, two and a half if youre lucky). Hence the journey to the farm: we need collards, lots of them. And while we might be able to buy twenty-five heads of New Jersey, California, or North Carolinagrown collards from a supermarket downtown, driving twenty-six miles round-trip for local collards well, thats just what Charlestonians do, honoring special occasions with the best, freshest ingredients we can find. Joseph Fields organic collards, just-picked, are our insider tip.

As we follow Mr. Fields down the row, we watch as he pinches off the top of the planta bright-green, bud-like form sprouting immature yellow flowersand pops it in his mouth. Collard topstastiest part of the plant, he says, and offers the next ones to us. And hes right: these shoots are tender like pea greens, but with an astonishing pepperinesslike horseradish and chiles in the same bite. In all our years growing up here, and cooking, eating, and writing here as adults, weve never encounteredor consideredcollard tops.

By the time our crates are full, the fog has lifted and chickens are scrabbling the ground near where weve parked our car. We pay Mr. Fields and say our goodbyes. In the car, we cant shake those collard topssomething virtually absent from the marketplace, but so plentiful if you know where to look. We get to thinking how we might focus that peppery flavor of the tops in a pot of greens, by backing off on the bacon and amping up the peppers. Thatll be the days experimentand the greens we serve at the oyster roast.

CHARLESTON HAS ALWAYS BEEN FOR US A PLACE OF DISCOVERIES , firsts, and small miracles in the realm of food. For kids born here, food is like language, a body of knowledge absorbed almost unconsciously; you taste your first oyster before youre two years old, and by the time youre five its just what you eat. But we were born in New York, and we moved to Charleston with our parents and our sister when we were eight and ten. We had so much catching up to do.

Our family landed in a 1784 townhouse on Rainbow Row, a stretch of East Bay Street where almost every house is attached, and each stucco faade is painted a different pastel hue (ours was warbler-yellow). The upper floors had an expansive view of Charleston Harbor that stretched past the boatyard of the Carolina Yacht Club to Fort Sumter in the distance, and we could take in the seagulls, the dolphins, the container ships cruising the middle distance. In the immediate foreground wasstill isthe baseball diamond at the Hazel V. Parker Playground, a park where we joined the phalanxes of kids riding around on BMX bikes and skateboards. It was here, climbing a tree that grew on the fence line between the playground and the yacht club, that we tasted mulberries for the first time. Our new friends showed us to look for the ripest, purple-black ones and we experienced their strangely mellow-sweet berry flavor. We ate until our teeth turned blue and our shirts were stained. There was also new vocabulary to learn: benne , for the sesame found in salty-sweet, molar-sticking candy and in tiny little crisp cookies; scuppernongs , grapes as syrupy-sweet as the word was funny to say, with a range of flavors depending on their ripeness. In time, we could tell just by feeling them which ones we would like best. We learned that peanuts could be eaten wet, boiled to a bean-like consistency, and in short order we discovered loquats, toofuzzy yellow-skinned fruits you could peel, eating the small amount of sweet-tart flesh that clung to the seeds. Or you could pop the whole thing in your mouth, munch on it, and then spit out the skin and the seeds.