The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Youre only as good as your last souffl.

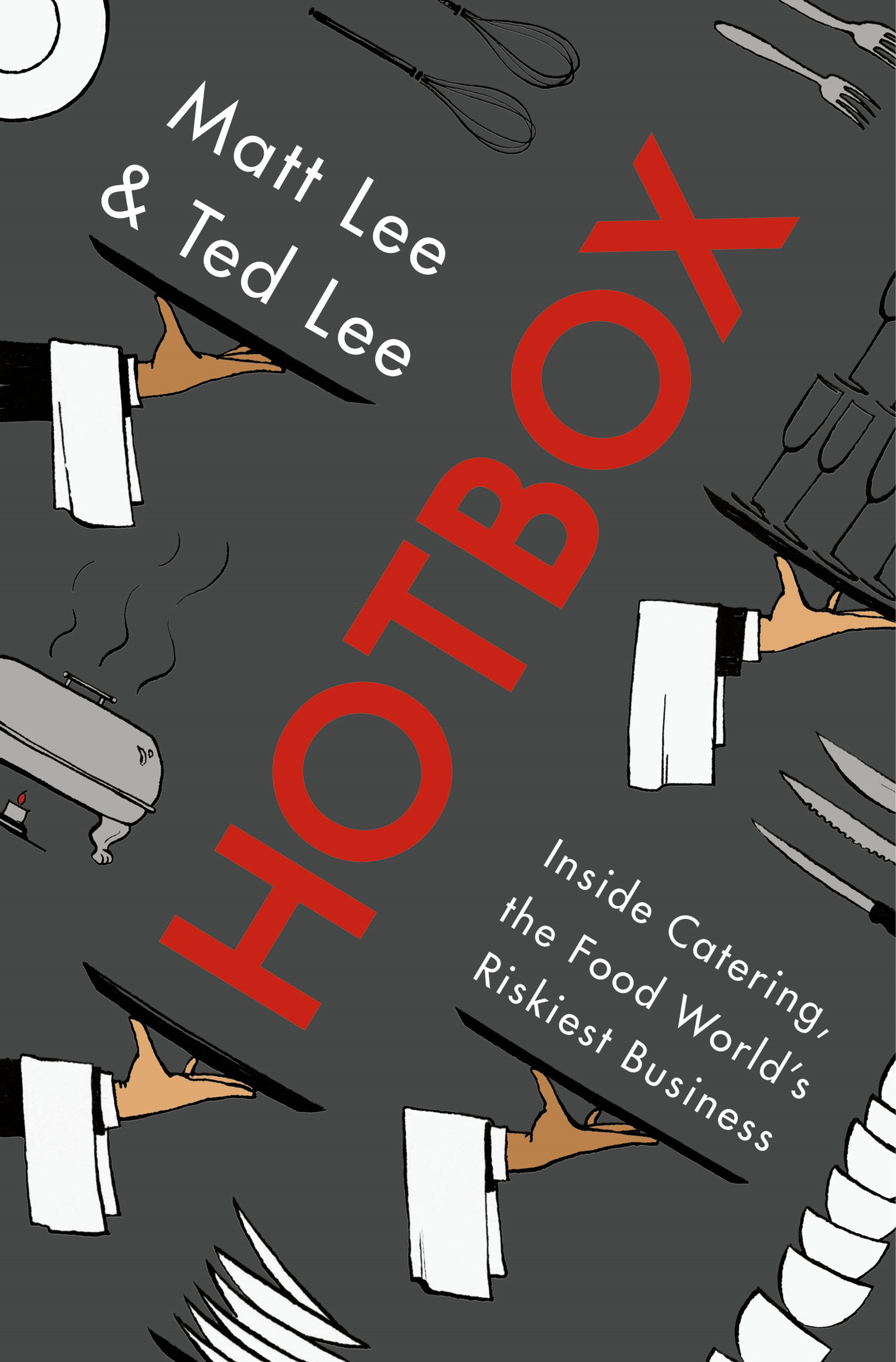

We Know What Youre Thinking Catering? Like, rubber-chicken dinners?

We know youre thinking this because we were once like you. Not so long ago, we considered catering the elevator music of the culinary arts: when a chef scales up the numbers of plates into the hundreds and thousands, how could the quality of food not suffer?

So just hear us out. And come along with us, to narrow, tree-lined West Twelfth Street in Manhattans Greenwich Village. Step inside the tall brick town houseas it happens, a landmark of American gastronomywhere a chance encounter with a trio of catering chefs lured us into their largely hidden world and utterly upended our thinking about rubber chicken and dry salmon.

Wed been invited by two friends, restaurant chefs from Atlantas acclaimed Miller Union, to observe a special dinner they were cooking at the James Beard House, the former residence of food journalist, cookbook author, and pope of American food, James Beard. Almost every night of the year, the James Beard House hosts guest chefs from restaurants all around the country, invited by the James Beard Foundation (the food worlds Academy, whose annual awards show is the restaurant communitys Oscars) to prepare their most impressive dishes for a crowd of eighty food-obsessed New Yorkers and members of the food press. Cooking at the Beard House is a great honor, but no single chef whos worked its kitchen there would say its a pleasure: the scale of the space is residential, but with hulking commercial ovens and dishwashers the ground floor heats up rapidly. That night was a ridiculously warm one in June.

Knowing well the challenges of the house, our Atlanta friends had recruited a buddy of theirs, Patrick Phelan, executive chef for a top New York caterer, Sonnier & Castle, to help them. And Patrick brought along his coworkers Juan and Jorge Soto. When the three caterersall in their thirtiesarrived in the kitchen, they had a wholly different mien from the Atlanta guys, Steven Satterfield and Justin Burdett. Youve probably seen your share of restaurant chefs in real life or on TV, and know they roll with a certain flair, with brio, tattoos and piercings, statement hair (or facial hair), rare Japanese knives, their names embroidered on their chef coats. By contrast, the caterers affect revealed almost nothing: Patrick, Juan, and Jorges chefs jackets bore no names and they wore black polyester pillbox-style beanies. They pulled generic knives wrapped in dish towels from fraying, lumpy backpacks. None of the three had seen this kitchen before the evening they arrived, nor had they ever cooked the recipes they were about to produce. They blended into the wallpaper, anonymous to almost everyone dining at and even working this event, but something about the way they sized up this unfamiliar kitchen nevertheless conveyed gravitas. These were Special Ops culinary mercenaries, poised for a battle.

Since there was barely room enough for the five chefs, we spent the evening observing the plating up of dishes from the kitchen doorway and ferrying deli containers of ice water into the inferno. Things started to really accelerate when it came time to fire the third and fourth courses, eighty servings each of a sauted quail and a braised oxtail crepinette (a crispy little puck), both of which needed to be burnished brown and cooked just rightnot overdoneand in an instant. For the next half hour the three caterers were everywhere at once, slammed as any restaurant line at 8:45 p.m., but entirely in control. (Satterfield moved to the other side of the serving counter, to expedite and apply finishing touches, and to otherwise stay out of the way.) Without a wasted gesture or motion, the catering chefs worked sheet pans in ovens and saut pans on every burnerat times sheet pans on raging burners, a makeshift griddle!as gracefully and agilely as modern dancers. Their clipped dialogue was inscrutable to us, the vocabulary unfamiliar, issued at low volume amid the clatter. Hand, elbow, and head gestures were sufficient for most of what they needed to say to each other.

The dinner was a huge success, due in no small part to Patrick, Juan, and Jorge, and the food that evening was everything the restaurant chefs could have hoped for: exquisitely delicious, perfectly executed, on a par with the food Miller Union serves every day back home in Atlanta. (Satterfield has since won a James Beard Award.)

Afterward we followed the Sonnier & Castle crew to a bar nearby. When we marveled at their virtuosity with an unfamiliar menu in suboptimal circumstances, both Sotos smiled and shrugged.

De nada, Juan said, laughing.

Jorge turned serious. You gotta understand. For us? This is fun.

We didwhat?eighty covers tonight? Patrick added. These guys can do lamb chops for fourteen hundred. I tell them I need three hundred well-done, three hundred rare, eight hundred medium-rare. I tell them what time to serve-out. And I can walk away.

Its not too hard, Juan said. You have to know the proofer.

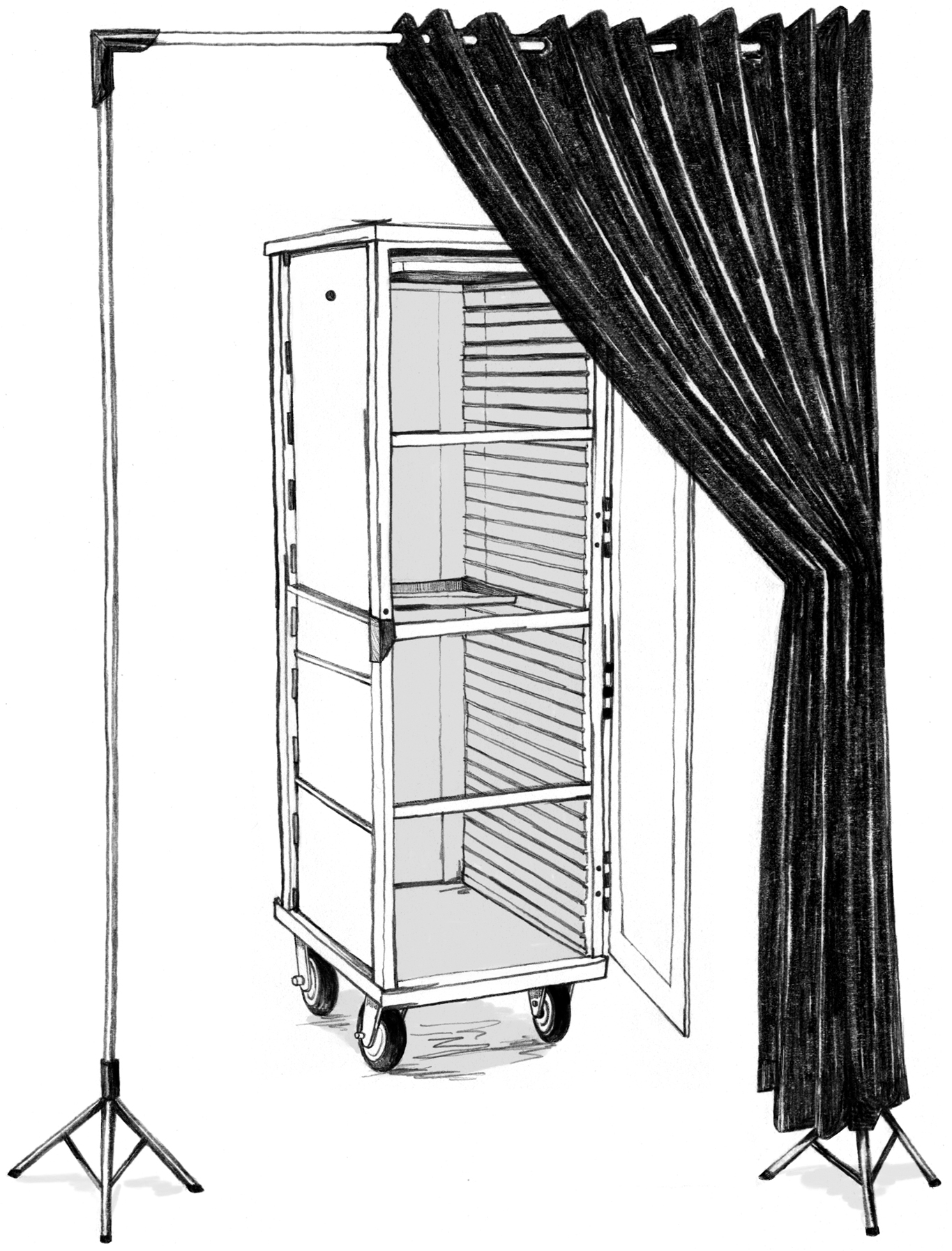

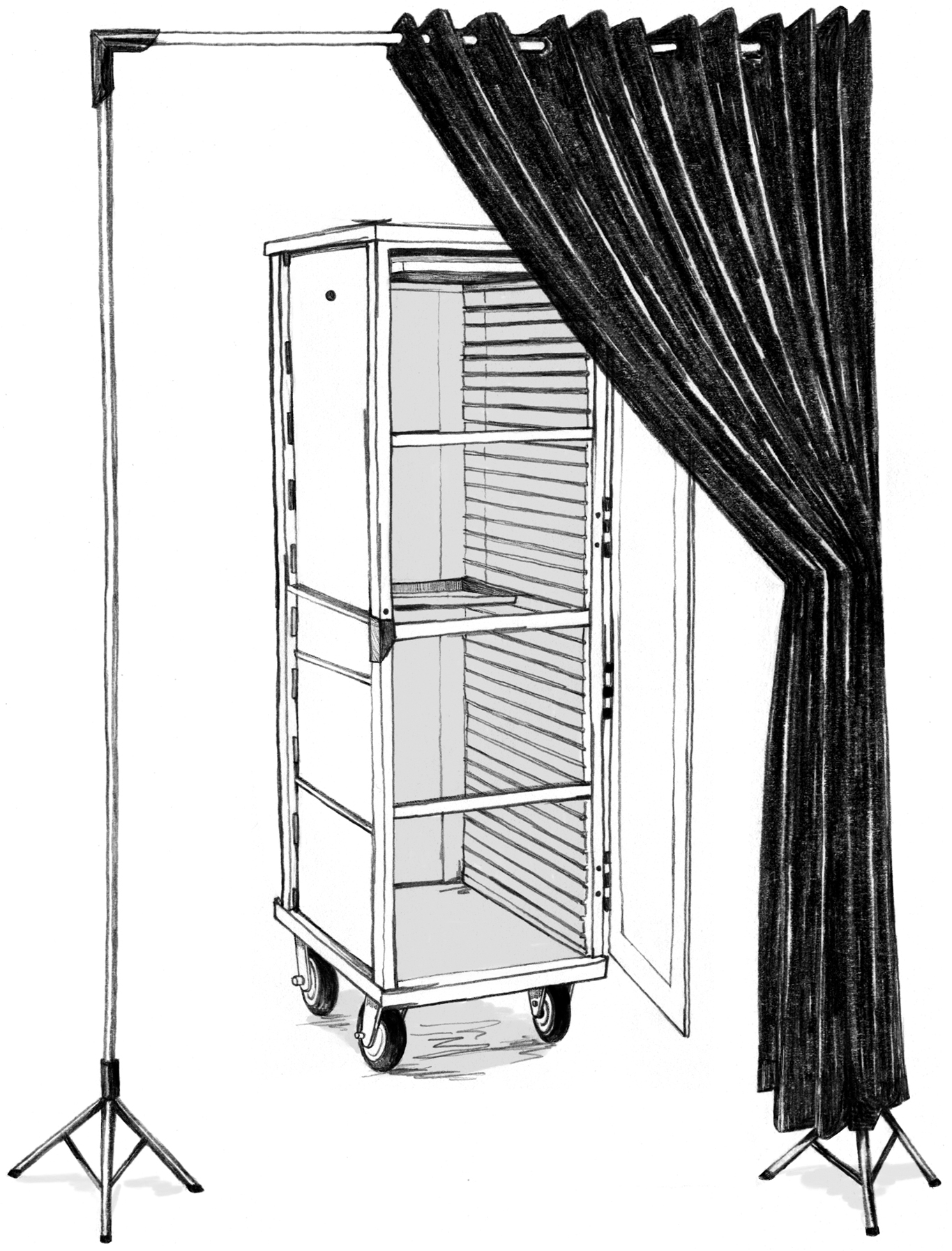

Patrick explained: the proofer is another word for the hotboxan upright aluminum cabinet on wheels, lifeblood for caterersthat conveys the partially cooked food from the refrigerator at the caterers prep kitchen to the site of the party. So those lamb chops for fourteen hundred would have been seared in advance at the caterers prep kitchen, just enough to get perfect coloring on the outside, but more or less raw inside. Then they slide on sheet pans into the proofer. The proofer rolls into a fridge to chill until its time to move them onto the truck for the ride to the venue. Once on-site, the hotboxes are emptied and transformed into working ovens, with each sheet pan of lamb placed over other sheet pans that hold only lit cans of Sterno.

Sterno? we protested. Isnt that for keeping chafing pans of rubber chicken warm on a hotel buffet?

Not in catering at this level, he explained. All hot event food consumed in New York City gets heated and finished in this way. The side dishes for that lamb, the quinoa, roasted parsnips, whatever. Even the bread and the plates. All of it comes out of a hotbox.

You have to watch, Juan added, pointing to his eye. Feel, he said, rubbing his thumb between his forefingers. And listen. He tugged an earlobe. And organize. Always organize. But if you do, you can get it right.

We were certain we could not get it rightneither of us has the sensory knowledge, the mettle, or the wits. But the more we listened to these catering pros, the more captivated we were by their strange world of food-crafting-in-the-field, unlike anything wed ever seen go down in a home or restaurant.

Patrick prodded Juan to tell us a horror story, about the time a hot proofer got too close to a sprinkler head at the New York Public Library and the plating linefood, chef, kitchen assistantsgot soaked in a rust-water rain and still managed to serve dinner to three hundred people oblivious to the back-of-house disaster. You had to be cool, calm, and, especially, resourceful, whatever situation you were dealt, whether it was being conscripted from the kitchen to translate Venezuelan president Hugo Chvezs Spanish into English for Oliver Stone, or discovering, only at the moment when she stepped into the yachts kitchen afterward, that youd cooked an intimate thirtieth birthday dinner for Kim Kardashian.