Also by William J. Bernstein

WILLIAM J. BERNSTEIN

To Jane

ix

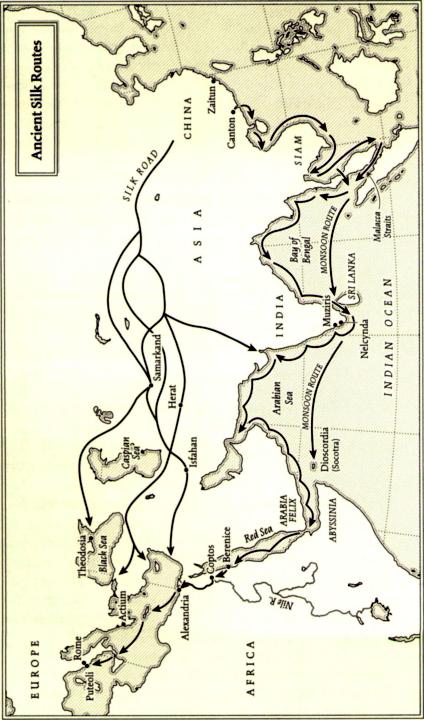

Ancient Silk Routes 3

World Trade System, Third Millennium BC 25

Ancient Canals at Suez 37

Winter Monsoon Winds and Summer Monsoon Winds 39

Athenian Grain Routes 45

Incense Lands and Routes 63

The World of Medieval Trade 80

The Spice Islands 114

Eastern Mediterranean Spice/Slave Trade, Circa AD 1250 126

The Black Death, Act I: AD 540-800 137

The Black Death, Act II: 1330-1350 141

The Tordesillas Line in the West 169

Da Gama's First Voyage, 1497-1499 171

The Global Wind Machine 201

Banda (Nutmeg) Islands 227

Strait of Hormuz 231

Dutch Empire in Asia at its Height in the Seventeenth Century 233

Coffee-Growing Area and Ports of Late-Medieval Yemen 250

The Sugar Islands 269

Pearl River Estuary 285

The Erie Canal and Saint Lawrence Systems in 1846 325

World Oil Flows, Millions of Barrels per Day 368

The circumstances could not have been more ordinary: a September morning in a hotel lobby in central Berlin. While the desk clerk and I politely exchanged greetings in each other's fractured English and German, I casually plucked an apple from the bowl on the counter and slipped it into my backpack. When hunger overtook me a few hours later, I decided on a quick snack in the Tiergarten. The sights and sounds of this great urban park nearly made me miss the tiny label that proclaimed my complimentary lunch a "Product of New Zealand."

Televisions from Taiwan, lettuce from Mexico, shirts from China, and tools from India are so ubiquitous that it is easy to forget how recent such miracles of commerce are. What better symbolizes the epic of global trade than my apple from the other side of the world, consumed at the exact moment that its ripe European cousins were being picked from their trees?

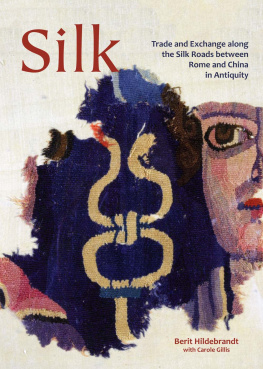

Millennia ago, only the most prized merchandise-silk, gold and silver, spices, jewels, porcelains, and medicines-traveled between continents. The mere fact that a commodity came from a distant land imbued it with mystery, romance, and status. If the time were the third century after Christ and the place were Rome, the luxury import par excellence would have been Chinese silk. History celebrates the greatest of Roman emperors for their vast conquests, civic architecture, engineering, and legal institutions, but Elagabalus, who ruled from AD 218 to 222, is remembered, to the extent that he is remembered at all, for his outrageous behavior and his fondness for young boys and silk. During his reign he managed to shock the jaded populace of the ancient world's capital with a parade of scandalous acts, ranging from harmless pranks to the capricious murder of children. Nothing, however, commanded Rome's attention (and fired its envy) as much as his wardrobe and the lengths he went to flaunt it, such as removing all his body hair and powdering his face with red and white makeup. Although his favorite fabric was occasionally mixed with linen-the so-called sericum-Elagabalus was the first Western leader to wear clothes made entirely of silk.

From its birthplace in East Asia to its last port of call in ancient Rome, only the ruling classes could afford the excretion of the tiny invertebrate Bombyx mori-the silkworm. The modern reader, spoiled by inexpensive, smooth, comfortable synthetic fabrics, should imagine clothing made predominantly from three materials: cheap, but hot, heavy animal skins; scratchy wool; or wrinkled, white linen. (Cotton, though available from India and Egypt, was more difficult to produce, and thus likely more expensive, than even silk.) In a world with such a limited sartorial palette, the gentle, almost weightless caress of silk on bare skin would have seduced all who felt it. It is not difficult to imagine the first silk merchants, at each port and caravanserai along the way, pulling a colorful swatch of it from a pouch and turning to the lady of the house with a sly, "Madam, you must feel this to believe it."

The poet Juvenal, writing around AD 110, complained of luxuryloving women "who find the thinnest of thin robes too hot for them; whose delicate flesh is chafed by the finest of silk tissue."2 The gods themselves could not resist: Isis was said to have draped herself in "fine silk yielding diverse colors, sometime yellow, sometime rose, sometime flamy, and sometime (which troubled my spirit sore) dark and obscure."3

Although the Romans knew Chinese silk, they knew not China. They believed that silk grew directly on the mulberry tree, not realizing that the leaves were merely the worm's home and its food.

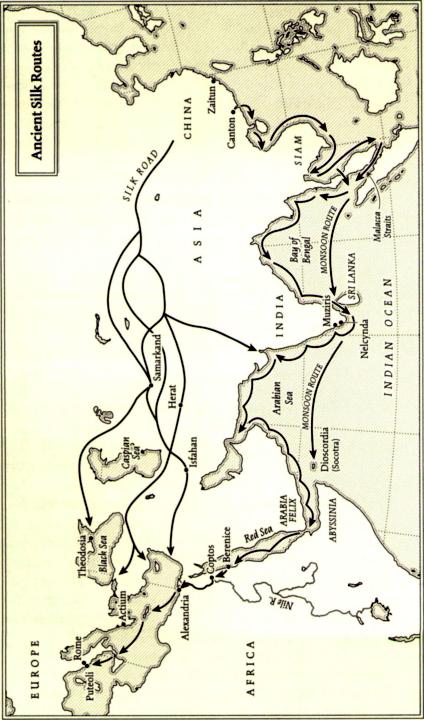

How did goods get from China to Rome? Very slowly and very perilously, one laborious stage at a time.4 Chinese traders from southern ports loaded their ships with silk for the long coastwise journey down Indochina and around the Malay Peninsula and Bay of Bengal to the ports of Sri Lanka. There, they would be met by Indian merchants who would then transport the fabric to the Tamil ports on the southwest coast of the subcontinent-Muziris, Nelcynda, and Comara. Here, large numbers of Greek and Arab intermediaries handled the onward leg to the island of Dioscordia (modern Socotra), a bubbling masala of Arab, Greek, Indian, Persian, and Ethiopian entrepreneurs. From Dioscordia, the cargo floated on Greek vessels through the entrance of the Red Sea at the Bab el Mandeb (Arabic for "Gate of Sorrows") to the sea's main port of Berenice in Egypt; then across the desert by camel to the Nile; and next'by ship downstream to Alexandria, where Greek Roman and Italian Roman ships moved it across the Mediterranean to the huge Roman termini of Puteoli (modem Pozzuoli) and Ostia. As a general rule, the Chinese seldom ventured west of Sri Lanka, the Indians north of the Red Sea mouth, and the Italians south of Alexandria. It was left to the Greeks, who ranged freely from India to Italy, to carry the greatest share of the traffic.

With each long and dangerous stage of the journey, silk would change hands at dramatically higher prices. It was costly enough in China; in Rome, it was yet a hundred times costlier-worth its weight in gold, so expensive that even a few ounces might consume a year of an average man's wages.5 Only the wealthiest, such as Emperor Elagabalus, could afford an entire toga made from it.