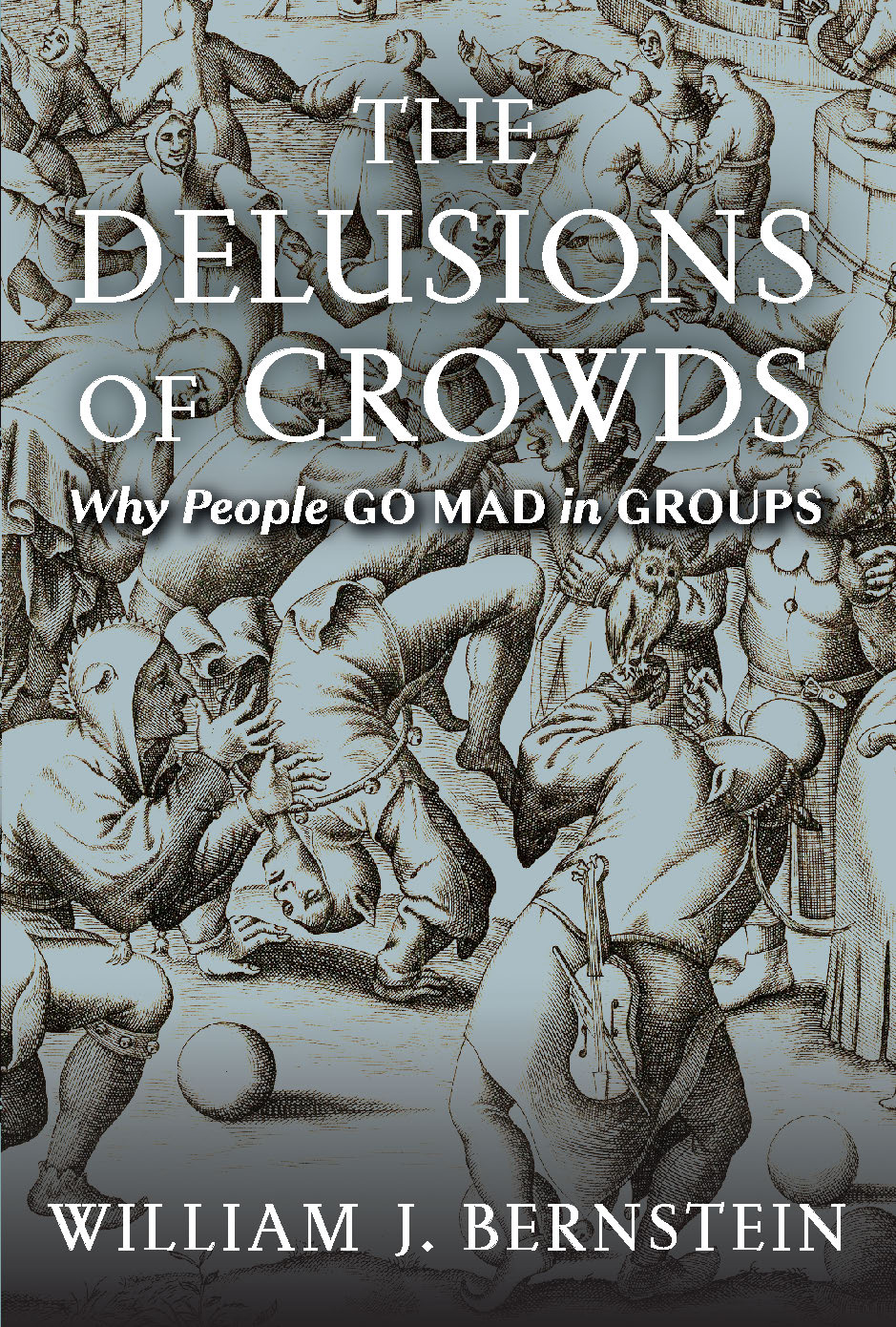

THE

DELUSIONS

OF CROWDS

Also by William J. Bernstein

Rational Expectations:

Asset Allocation for Investing Adults

Masters of the Word:

How Media Shaped History

The Investors Manifesto:

Preparing for Prosperity, Armageddon, and Everything in Between

A Splendid Exchange:

How Trade Shaped the World from Prehistory to Today

The Birth of Plenty:

How the Prosperity of the Modern World Was Created

The Four Pillars of Investing:

Lessons for Building a Winning Portfolio

The Intelligent Asset Allocator:

How to Build Your Portfolio to Maximize Returns and Minimize Risk

THE

DELUSIONS

OF CROWDS

Why People GO MAD in GROUPS

WILLIAM J. BERNSTEIN

Atlantic Monthly Press

New York

Copyright 2021 by William J. Bernstein

Jacket design by Brbara Abbs

Jacket artwork Festival of Fools , Pieter van der Heyden, (Holland, 1525-1569)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011, or .

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in Canada

First Grove Atlantic hardcover edition: February 2021

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

ISBN 978-0-8021-5709-6

eISBN 978-0-8021-5711-9

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

To Kate, Johanna, and Max

Contents

It has been in print ever since.

Mackay chronicled the end-times delusions that supposedly gripped Europe as it approached the year a.d . 1000, as well as the remarkable religious madness of the Crusades. The books best known chapters, though, detail the financial mass delusions of the Dutch tulipmania of the 1630s and the twin stock market bubbles in Paris and London in 17191720. These episodes, which constitute the first three chapters, are what propelled the book to its long-lasting fame.

Mackay was certainly not the first to intuit the contagious nature of human irrationality. Consider, for example, this passage from Herodotus:

When [Darius] was king of Persia, he summoned the Greeks who happened to be present at his court, and asked them what they would take to eat the dead bodies of their fathers. They replied that they would not do it for any money in the world. Later, in the presence of

The Greeks, after all, were antiquitys intellectuals, and Darius must have been tickled to box their rhetorical ears. His unspoken messages to the Greeks: You may be the most learned among humankind, but you are just as irrational as the rest of us; you are simply better at rationalizing just why, despite all evidence to the contrary, you are still right.

While the ancients and Mackay were well acquainted with human irrationality and popular manias, they could not know their precise biological, evolutionary, and psychosocial wellsprings. Mackay, for example, must have asked himself exactly why groups of people, from time to time, chase the same ludicrously overpriced investments en masse.

Today, we have a much better idea of how this happens. In the first place, financial economists have discovered that human beings intuitively seek out outcomes with very high but very rare payoffs, such as lottery tickets, that on average lose money but tantalize their buyers with the chimera of unimaginable wealth. In addition, over the past several decades, neuroscientists have uncovered the basic anatomic and psychological mechanism behind both greed and fear: the so-called limbic system, which lies close by the vertical plane that divides the brain between its right and left hemispheres. One symmetrically placed pair of the limbic systems structures, the nuclei accumbens (singular: nucleus accumbens), lie approximately behind each eye, while another pair, the amygdalae (singular: amygdala), sit just under the temples.

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), researchers have found that the nuclei accumbens fire not only with reward, but even more intensely with its anticipation, be it culinary, sexual, social, or financial. In contrast, the amygdalae fire with disgust, fear, and revulsion. If, for example, you adore your aunt Flos lasagna, your nuclei accumbens and their connections will fire ever more rapidly on the way over to her house, and likely peak just as the aroma wafts from the serving dish. But as soon as the first bite is taken, their firing rate decreases, and if your

The benefit of an active anticipatory circuitry seems obvious; Mother Nature favors those who anticipate and strive, whereas the enjoyment of satiation, once achieved, offers little evolutionary advantage. And few things likely stimulate the nuclei accumbens as does the knowledge that some of those around us are becoming effortlessly wealthy. As economic historian

Novelists and historians have known for centuries that people do not deploy the powerful human intellect to dispassionately analyze the world, but rather to rationalize how the facts conform to their emotionally derived preconceptions. Journalist

Over the past several decades, psychologists have accumulated experimental data that dissect the human preference of rationalization over rationality. When presented with facts and data that contradict our deeply held beliefs, we generally do not reconsider and alter those beliefs appropriately. More often than not, we avoid contrary facts and data, and when we cannot avoid them, our erroneous assessments will occasionally even harden and, yet more amazingly, make us more likely to proselytize them. In short, human rationality constitutes a fragile lid perilously balanced on the bubbling cauldron of artifice and self-delusion so lucidly illustrated by Mackay.

Mackays own behavior demonstrated just how susceptible even the most rational and well-informed observers can be to a financial mania. Shortly after he published Extraordinary Popular Delusions in 1841, England experienced a financial mania that revolved around the great high-tech industry of the time, the railroad, which was even larger than the twin bubbles that swept Paris and London in 17191720. Investors, greedy for stocks, underwrote the increase in Englands track mileage from two thousand in 1843 to five thousand in 1848, and thousands of more miles were planned but never built when shares finally went bust. If anyone should have foreseen the collapse, it was Mackay.

He did not. During that mania, he served as the editor of the Glasgow Argus , where he covered the ongoing railroad construction with a notable lack of skepticism and when he published the second edition of Extraordinary Popular Delusions in 1852, he gave it only a brief footnote.

Financial manias can be thought of as a tragedy like Hamlet or Macbeth , with sharply defined characters, a familiar narrative arc, and well-rehearsed lines. Four dramatis personae control the narrative: the talented yet unscrupulous promoters of schemes; the gullible public who buys into them; the press that breathlessly fans the excitement; and last, the politicians who simultaneously thrust their hands into the till and avert their eyes from the flaming pyre of corruption.