vii

IN THE 196os, when I began writing profiles of scientists for The New Yorker, an obvious subject would have been Robert Oppenheimer. In the first place, I knew and admired him. During the two years I spent-1957-1959-at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, where he was the director, I was able to observe him on an almost daily basis. We also had some private talks, one of the most memorable of them on a train ride from Princeton to New York, during which he spoke a little about what he referred to as his "case"-the famous 1954 hearing before the Atomic Energy Commission in which he lost his securih' clearance. This aside, many of my teachers had either been at Los Alamos or before the war had studied under Oppenheimer in California. They told me all sorts of stories.

I also knew something about his physics. There is a tendency to dismiss Oppenheimer as a physicist, perhaps partly because he seemed disappointed in what he had been able to do. But his standards were impossibly high. He was a superb physicist. Had he lived longer-he died in 1967, at the age of sixty-two-the pioneering work that he and his students did on neutron stars and black holes would have, I am convinced, been widely honored, possibly by a Nobel Prize. Because of his ability in physics, and his astounding charisma, he did at Los Alamos what I think no one else would have been able to do. If Oppenheimer had not been the director at Los Alamos, I am persuaded that, for better or worse, the Second World War would have ended very differently-without the use of nuclear weapons. They would not have been ready. In short, Oppenheimer was a profile writer's dream. Nonetheless I decided that he was not a subject for me.

There were several reasons, two of them involving The New Yorker. About this time William Shawn, its editor, told me that he had asked Oppenheimer to write something for the magazine. Oppenheimer was willing, but only on the condition that nothing he wrote could be changed in any way, including punctuation. Mr. Shawn explained to me that he could not possibly turn over his editorial responsibilities to Oppenheimer or anyone else. That ended that.

The second incident involved me directly. On November 18, 1962, Niels Bohr died at the age of seventy-seven. In the hierarchy of twentieth-century physicists I would place Bohr just below Einstein. I composed a tribute to him for The New Yorker, which was designed to go into the Notes and Comments section of the Talk of the Town. I wrote what I thought was an affectionate, brief profileobituary. In it I quoted something that Oppenheimer had written about Bohr's contribution to the quantum theory. As was the custom of The New Yorker's fact checkers, they called Oppenheimer. Not only did they vet the quote, they read him the whole piece as context. They then called inc to report that Oppenheimer had told them that what I had written was terrible and that I should call him. When I did so, he more or less repeated this to me but offered no suggestions as to how I might improve the piece except to insist that I remove his quotation. Needless to say, I was crushed.

As it happened, I was then spending a fair amount of time at the Rockefeller University, where one of the senior professors was the late George Uhlenbeck. Uhlenbeck, who had been born in Java and schooled in Ilolland, was well known in our community as both a physicist and a person of great wisdom and common sense. lie had known both Oppenheimer and Bohr for decades. Oppenheimer had spent time in Leiden and had learned Dutch. I decided I would show what I had written to Uhlenbeck, and if lie too said it was awful I would withdraw it. Uhlenbeck read it and told me it was fine. Ile conjectured that Oppenheimer was annoyed because he had not been asked to write Bohr's obituary. Uhlenbeck also supplied the lyrics to a song they used to sing in Holland to the tune of the Dutch national anthem. Each verse ended with "En Bohr, en Einstein hebben wij atijd vereed" (And Bohr and Einstein we have always revered). This replaced the Oppenheinmer quote in my obituary for Bohr. Incidentally, after Oppenheimer died I wrote his obituary for The New Yorker.

But there was an even deeper reason why I did not want to try to write Oppenheimer's profile. The way I worked was to spend hours taping interviews with my subjects. These recorded interviews really are oral biographies. If I was to do Oppenheimer, that is what I would have attempted. But even assuming he would grant me the time and access, I did not think I could ask him the questions I wanted to. I probably could have asked him how he felt about nuclear weapons and his role in them. Did he still feel, as he told President "Truman, that he had "blood on his hands"? I am sure I could have discussed his physics and the physics of his contemporaries. But what about his personal life? Could I have asked him about his affair with Jean Tatlock in the late 1930s which led to his flirtation with the Communist party? Could I have asked him about his ambiguous feelings about being Jewish? Is this what caused him to drop his first name "Julius" for the letter "J," which he always insisted stood for "nothing"? I might have asked him why he never added anything to the art he inherited from his father-the van Goghs, among other things. These were the kinds of things one would wonder about if one was writing a biography as opposed to a hagiography. In short, I felt I would run into a wall, so I never got started.

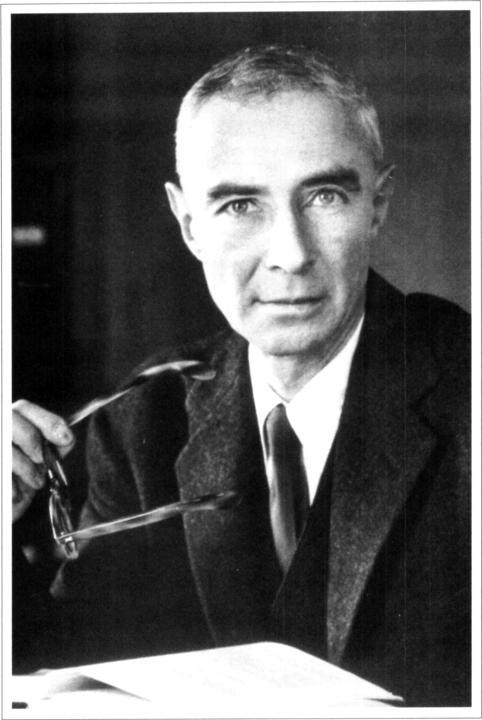

Nonetheless the subject pursued me. Inevitably it came up in profiles of other scientists. I read and reread the transcript of Oppenheimer's hearing-a sort of tragic play-and any of the biographies that mentioned him. Facts kept accumulating like bales of hay. On the wall of the room in which I am writing there is a photograph of Oppenheimer. It is one that he gave my father. Oppenheimer is clearly dressed in one of the specially tailored shits he bought at Langrock's in Princeton. (They too had a picture of him.) His hair is cut very short, and his right ear protrudes. He looks both extremely intelligent and very wary. He is not looking at the photographer, and since the photo is in black and white you cannot see the remarkable blue of his eyes. He has a cigarettethey eventually killed him-in his left hand held between two tapered fingers. It is a face that would get your attention anywhere, even if you did not know anything about the person it belonged to. Someone once said that when Dr. Johnson entered a room he changed its electric charge. This was true of Oppenheimer. You could not be neutral.

As I accumulated my facts I kept staring at this picture and wondering if I now had enough distance from the events to write the profile I had meant to write in the ig6os. Things are both easier and more difficult-for the same reason. Nearly all the actors in this drama are dead. There are still a few of Oppenheimer's California students left, and a few of the people who were at Los Alamos with him, but nearly even' week I read a new obituary. This means that I am no longer constrained by their presence, but it also means that I can no longer get their advice. I make no pretense of trying to write a "definitive" biography of Oppenheimer. I leave this to others. Rather this is The New Yorker profile I never wrote.