VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

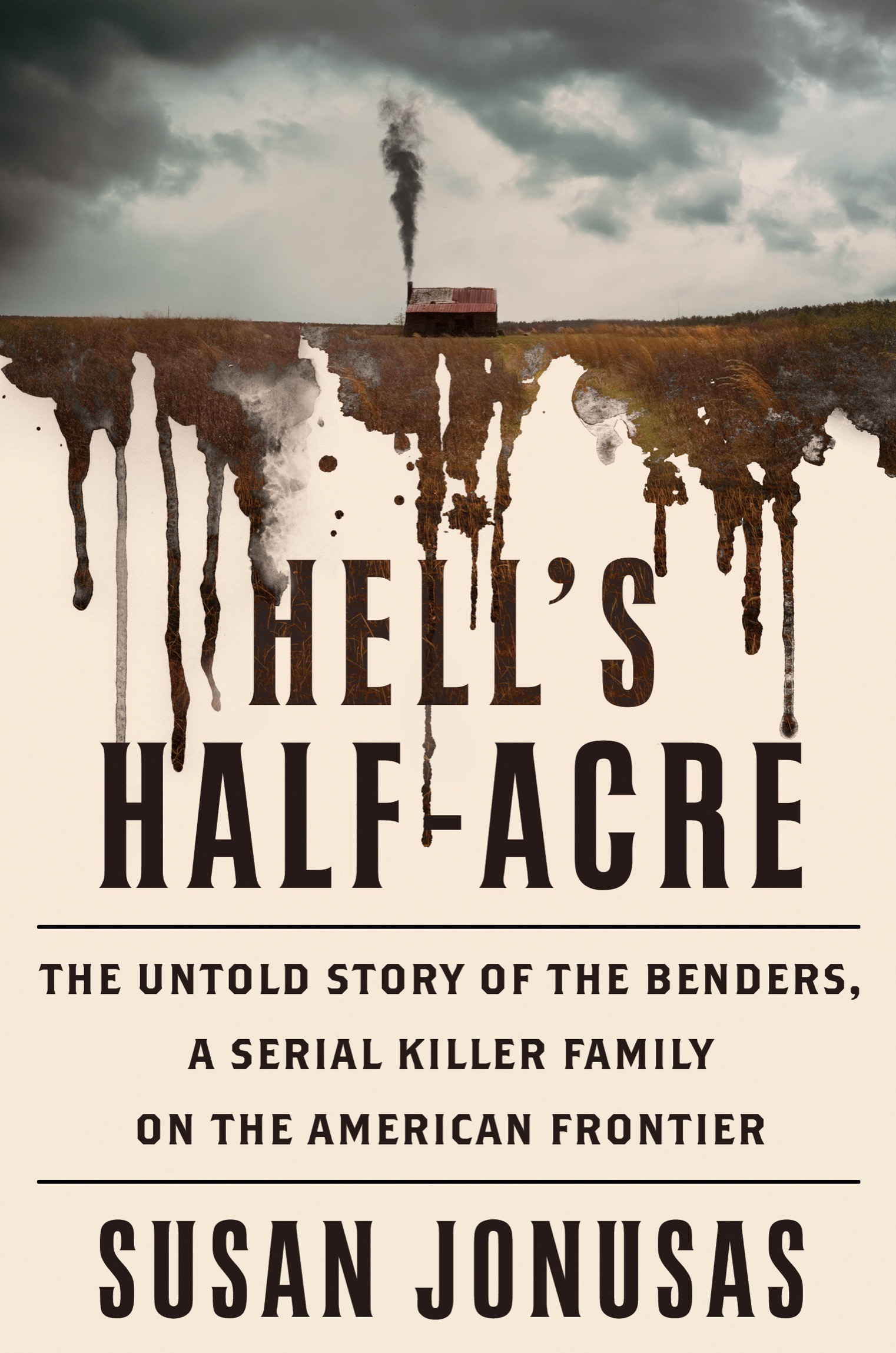

Copyright 2022 by Susan Jonusas

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Image credits: Kansas State Historical Society

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

Names: Jonusas, Susan, author.

Title: Hells half-acre : the untold story of the Benders, a serial killer family on the American frontier / Susan Jonusas.

Description: New York: Viking, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021024138 (print) | LCCN 2021024139 (ebook) | ISBN 9781984879837 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781984879844 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Bender family. | Serial murderersKansasLabette CountyHistory19th century. | Frontier and pioneer life.

Classification: LCC HV6533.K3 J66 2022 (print) | LCC HV6533.K3 (ebook) |

DDC 364.152/320978196dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021024138

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021024139

Cover design: Caroline Johnson

Cover images: (house) Amanda Greene / plainpicture; (clouds) Fiore / Shutterstock; (ink) iStock / Getty Images; (smoke) Trifonov Evgeniy / Getty Images

Book design by Daniel Lagin, adapted for ebook by Cora Wigen

Maps by Meighan Cavanaugh

pid_prh_6.0_139338311_c0_r0

For the victims

James Feerick, William Jones, Henry McKenzie, Benjamin Brown, William McCrotty, Johnny Boyle, George Longcor, Mary Ann Longcor, John Phipps, William York

and those who remain unknown

Evil is unspectacular and always human,

And shares our bed and eats at our own table.

W. H. Auden

Contents

Introduction

In the history of the American West, few historical figures have captured the public imagination like the outlaw. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the exploits of Jesse James, Pearl Starr, Billy the Kid, and numerous others filled newspapers and spilled over into dime novels. Their legacy continues to this day, cemented by Hollywoods technicolor Westerns and the grittier reimaginings of more recent years. In these stories, outlaws who cut a swath of violence across the high plains are struck down by the hand of justice. Alternatively, if the narrative suits, they are permitted a last-minute escape or tragic end defending others, perhaps against crooked lawmen or a greedy railroad tycoon. The outlaw, like its more law-abiding relative, the cowboy, is one of the most universally recognizable figures in American history. The word itself evokes nonconformity, the promise of freedom, the choice to carve out your own path against the status quo. Its a much beloved part of country music, a stock character whose reach spans nearly all genres. But it is also a central part of the mythologization of the West, a colonial narrative that obscures the reality of life on the frontier, sacrificing the more unpalatable history in favor of the overarching theme of progress.

The foundation for this narrative was laid over several centuries but came fully into being in the second half of the 1800s as America grappled with its identity in the aftermath of the Civil War. Stories of outlaws, gunslingers, Indians, sex workersknown colloquially as soiled dovesregulators, gamblers, prospectors, and pioneers entertained children and adults alike, solidifying their place in the fabric of the nation. A gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, exploded onto the newspapers and garnered those involved a notoriety that Wyatt Earp, a law enforcement officer at the scene, succeeded in transforming into celebrity later in his life. In 1883, Belle Starr, a wily female outlaw who harbored bandits at her ranch in Indian Territory, finally stood trial for horse thievery and found herself in a Detroit prison. The same year, William Cody, more recognizable by his nickname Buffalo Bill, founded Buffalo Bills Wild West. The touring attraction of actors, dancers, and popular frontier figures re-creating famous events from frontier history was a roaring success. Several rival productions emerged, but none could boast a cast list that included sharpshooter Annie Oakley, Hunkpapa Lakota leader Sitting Bull, and frontierswoman Calamity Jane. Buffalo Bill took his show all over the world. It was a glittering spectacle of gunpowder and horsemanship fundamental in shaping the international perception of the West and America as a whole at a time when the young country was still finding its place on the global stage. But it was also a PR stunt that allowed Americans to believe in a world that did not really existone where people did not stray into unknown moral territory or ask difficult questions about the state of the country.

If the Wild West shows presented a romanticized vision of the frontier, the numerous publications focused on the periods nastier individuals sought to capitalize on humanitys long-standing fascination with villains. A book entitled History, Romance and Philosophy of Great American Crimes and Criminals of the Various Eras of Our Country promised readers 161 superb engravings of the celebrated criminals. In its pages lurk familiar and unfamiliar faces. Some, like Cullen Bakeran unpredictable outlaw with ties to the Ku Klux Klanbarely made it out of the nineteenth century, their crimes too unpalatable for even the more lurid writers. Others, like Jesse James, became staples of cinema and literature for decades, reinvented as folk heroes despite their violent behavior and unwavering support for the Confederacy. Then there are the Bendersthe Kansas fiends, a family of murderers whose crimes sent the newspapers and the nation into a frenzy. Their case is a stark reminder that buried beneath the myth of the outlaw are very real criminals whose violence left an indelible imprint on communities across the frontier.

I first came across the story of the Bender family in a large, ghoulish book entitled More Infamous Crimes That Shocked the World. The book was from a local thrift shop, its blood red cover held together by decades-old tape. Within its pages, a chapter called The Bloody Benders introduced me to the family who committed a series of murders in southeast Kansas that caught the attention of the entire United States. At the heart of the case was Kate Bender, an enigmatic young woman whose involvement in the crimes catapulted them into notoriety. I was fascinated by her role in the story, having focused a large part of my studies on the treatment of the female criminal during the nineteenth century. Aligned with my work on criminal history is an enduring interest in America, imbued in me by my grandma, whose photo albums packed with images of the West enthralled me as a child. More Infamous Crimes presented me with a case that drew these existing interests together, but the chapter on the murders was vague and offered virtually no details about the victims or the historical context of the crimes. Tantalizingly, it also revealed what came to be the defining feature of the Bender murders: the culprits had simply disappeared.