Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

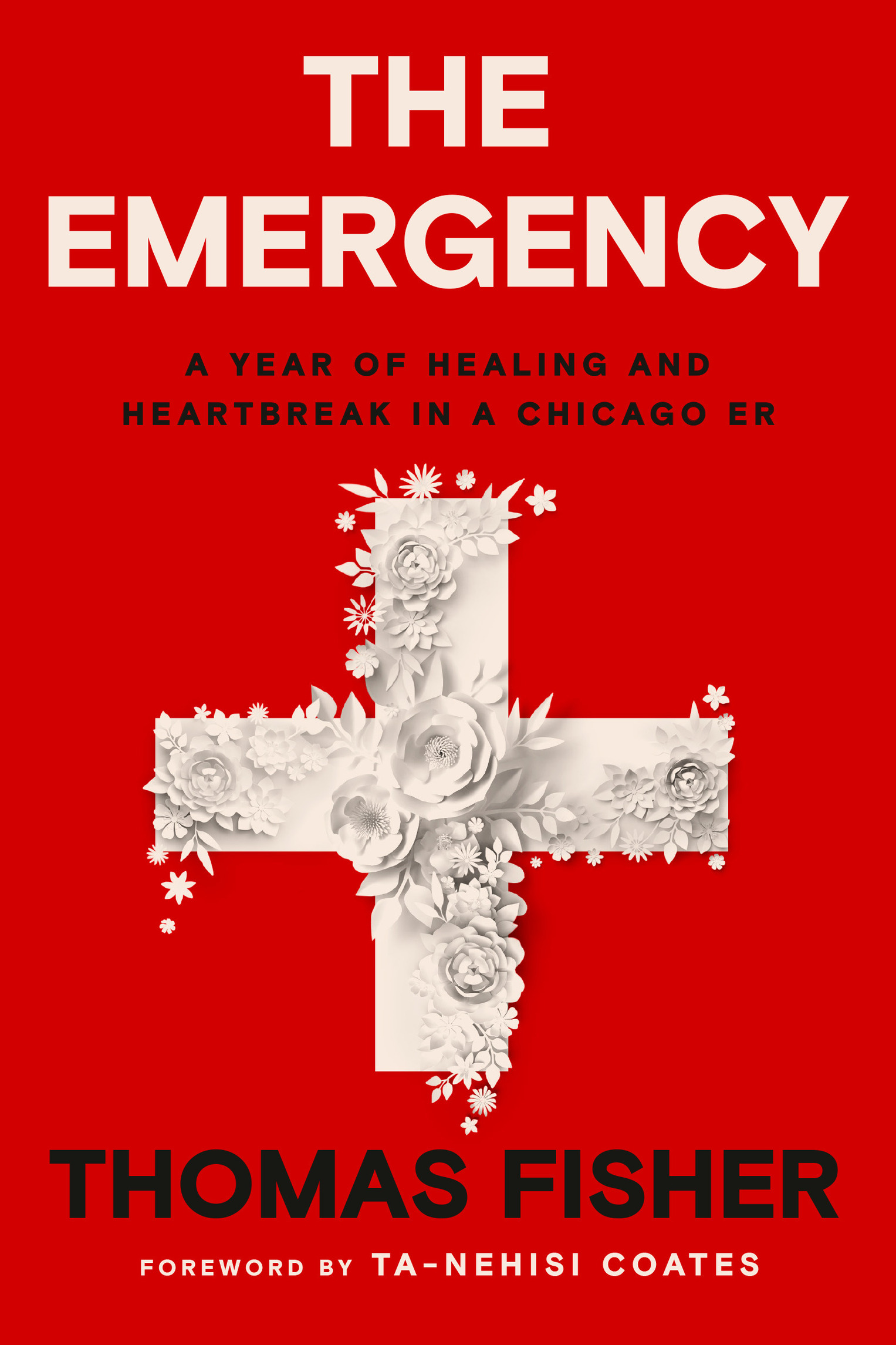

The Emergency is a work of nonfiction. The stories told in this book are based upon or derived from real-world medical situations. Most names and identifying details have been changed. With few exceptions, characters (both patients and hospital personnel) are edited composites of real people. The timing of when these medical experiences happened in relation to one another has also been changed. Resemblance to persons living or dead resulting from these changes is entirely coincidental and unintentional. While the events discussed in this book took place at the University of Chicagos Emergency Department, the events described can and do occur at other medical centers, clinics, and hospitals.

Copyright 2022 by Thomas Fisher

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

One World and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fisher, Thomas, author.

Title: The emergency: a year of healing and heartbreak in a Chicago ER / by Thomas Fisher.

Description: First edition. | New York: One World, [2022] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021039073 (print) | LCCN 2021039074 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593230671 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593230688 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: African AmericansMedical care. | African AmericansHealth and hygiene. | MinoritiesMedical care. | Medical careSocial aspects. | Discrimination in medical care. | EqualityHealth aspects. | HospitalsEmergency services.

Classification: LCC RA448.5.N4 F57 2022 (print) | LCC RA448.5.N4 (ebook) | DDC 362.1089/96073dc23

Ebook ISBN9780593230688

LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2021039073

LC ebook record available at lccn.loc.gov/2021039074

oneworldlit.com

randomhousebooks.com

Designed by Debbie Glasserman, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Michael Morris

Cover illustration: Michael Morris (cross), wacomka/shutterstock (flowers)

ep_prh_6.0_139458029_c0_r0

It should not be doubted that human life could be prolonged, if we knew the appropriate art.

Ren Descartes, Discourse on Method (1637)

Contents

FOREWORD

Ta-Nehisi Coates

ONE EVENING IN 2005, I drove over to see an old friend and classmate in the Bronzeville section of Chicago. Natalie MooreBig Nat, as we called herhad attended Howard with me and worked on the school newspaper. As young journalists, we had probably planned an evening of catching up and comparing craft notes. But there wasnt much craft discussed that evening, if only to keep from boring Big Nats other guest: Thomas Tom Fisher. Tom and Nat had both grown up on the South Side and had been friends since childhood. Id met Tom at Howard, where he would occasionally visit Nat. Beyond a love of food, drink, and crude jokes, what the three of us shared was a deep sense that our work must serve our community. For Nat and me, that responsibility manifested itself in our approach to journalismthe stories we told, the people we highlighted, the arguments we advanced. But for Tom, whod just finished his residency in emergency medicine, that responsibility was always more direct.

I remember how we commiserated over takeout and libations. I remember the oh my people jokes we made as music videos scrolled across the screen. But more than anything that happened in that apartment that night, I remember what happened outside it. When Id first arrived hours earlier, Id seen a group of young brothers seated on the stoop across from Nats apartment. They were having a party of their own. I pulled up, got out of my car, nodded the silent greeting of Black people the world over, and kept it moving. A few hours later, we heard gunshots. There was almost no alarm among us, save for the collective note that the shots seemed rather close. But we kept the party going until we saw police lights strobing through the windows. It was time to leave anyway. When Tom and I stepped outside, what we saw in the streets of Bronzeville was no great shock to either of uspolice tape on the sidewalk, the body of a young Black man laid out on the concretebut the moment is still indelible for me. And whatever weight it put on me, I knew even then, did not compare to what Tom would have to carry.

It was not merely that Tom was an ER doctor directly caring for those affected by the plague of gun violence that covered the country and levied a particular toll on Black neighborhoods. It was that those bodies were rushed into the ER from the streets that Tom called home. He was working not just for the Black community in general but for the same South Side of Chicago where his parents had settled and where he had been raised; he was caring for the lives and bodies of his neighbors. I dont think its too much to say that the lions share of Toms professional life has been consumed not only by treating the kind of violence we bore witness to that evening, but by an urgent attempt to understand why that violence tends to fall with such weight on the South Sides of America while barely grazing its Gold Coasts. It is those two labors that fill the pages of The Emergency: the work of Dr. Fishers hands, treating patients in the midst of a pandemic, and the work of his mind, trying to understand the larger system that delivers so many broken bodies from these streets into his care.

The answers he arrives at are not comforting. African Americans rank at the bottom of virtually every socioeconomic indicator. Health care is no exception. Explanations for this tend to focus on individual behavior. Confronted with the shocking death rates befalling Black people in the wake of COVID-19, Surgeon General Jerome Adams asserted that the Black community needed to step up and avoid alcohol, tobacco and drugs. Do it for your Big Momma, Adams asserted. Do it for your Pop-Pop. There is no data that shows Black people drinking, smoking, or drugging more than anyone else (and some that indicates they do so less.) But the point is comfort, not data. And it is simply more comforting to believe that the disproportionate impact of the worst pandemic in American history could have been avoided if Black people were monastic.

But TheEmergency joins a disturbing consensus increasingly being reached in the scholarship of powerthe vast chasms between the haves and have-nots of America are rarely benign mistakes amenable to behavioralism. The work of Ira Katznelson, Beryl Satter, and Richard Rothstein has demonstrated that the yawning wealth gap is the result not of poor spending habits but of federal policy. Eve Ewings research into Chicagos schools shows how school reform in Black communities ultimately destroyed the last outposts of the state, short of law enforcement. Devah Pagers studies of employment and incarceration show that employers evaluated Black men with no criminal record the same as white men with a criminal record. Moreover, this scholarship has demonstrated that the relationship between the powerful and the powerless is parasitic. The historian Edmund Morgan does not merely condemn American slavery but demonstrates how American notions of freedom depended upon it.

This is the tradition out of which The Emergency emerges. What it shows is that the health-care chasm is not an accident but a feature of white supremacy and American capitalism. But unlike the journalists, sociologists, and historians who must painstakingly recreate events and power dynamics from archives and interviews, Tom is a direct observer. He has seen the machine from every possible vantageas a doctor operating within it, as a public health scholar studying it, as a White House fellow working to shape policy, and as health-care leader trying to implement that policy. He comes to understand that long wait times in ERs like his on the South Side cost lives and allow for the spread of misery; that those wait times differ drastically from those in hospitals mere miles away; that the misery in one ER and the satisfaction in another are linked. He shows how even within a hospital ostensibly serving a poorer and blacker clientele, the relentless laws of capitalism lead the hospital to consider erecting a system of de facto Jim Crow health care.