EMILY C. FRANCOMANO

1. San Pedro, Diego de, active 1500. Crcel de amor.2. San Pedro, Diego de, active 1500 Translations Historyand criticism.3. San Pedro, Diego de, active 1500 Adaptations.4. San Pedro, Diego de, active 1500 Criticism and interpretation.5. Translating and interpreting Europe History 16th century.6. Books and reading Europe History 16th century.7. Spanish literature Classical period, 15001700 History andcriticism.8. Europe Intellectual life 16th century.I. Title.

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the Government of Ontario.

Acknowledgments

This is a book that I have wanted to write since my first semester in graduate school, when I took a seminar on the Spanish Sentimental Romances and learned that the works of Diego de San Pedro and Juan de Flores had been widely translated and used as language-learning tools in the sixteenth century. I am ever grateful to Patricia Grieve for introducing me to these works and for her unfailing guidance as I entered, and stayed in, academia. The idea that had been simmering away on the back-burner of my brain for more years than I wish to number here at last began to take shape with the support of an American Council of Learned Societies research fellowship in 2008, for which I am deeply grateful. The National Endowment for the Humanities summer seminar, The Reformation of the Book, 14501700, in 2009, directed by John King and James Bracken, provided invaluable space, time, and mentorship as the project took on more definite outlines. The Folger Library colloquium, Early Modern/Renaissance Translation, led by Anne Coldiron in the 201415 academic year, was a wonderful forum for testing my ideas as work on the book reached its conclusion. I was immensely fortunate to participate in these programs, which gave me the opportunity to discuss Book History and translation with many extraordinary scholars.

I wish to thank colleagues who so generously shared their expertise, read and commented upon drafts, invited me to give talks, and asked fruitful questions at conferences over the past years, especially Lourdes Alvarez, Heather Bamford, Lucia Binotti, Marina Brownlee, Joyce Boro, Robin Bower, Linde Brocato, Anne Coldiron, Vronique Duch-Gavet, Elizabeth Einstein, Irene Finotti, Leonardo Funes, Ethan Henderson, Gwen Kirkpatrick, Debbie Lesko-Baker, Sarah McNamer, Clara Pascual-Argente, Peter Pfeiffer, Sol Miguel Prendes, Joanne Rappaport, Jonathan Ray, Isidro Rivera, Ron Surtz, Chris Warner, and Barbara Weissberger. Georgetown University has been generous in its support for this project in the form of several summer grants, a semester of senior research leave, and in securing the publication subvention. I owe many thanks to the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at Georgetown, not least for contributing to the publication subvention, but first and foremost for providing talented research assistants from our graduate programs, some of whom are now colleagues: Tyler Bergin, Yoel Castillo Botello, Ins Corujo Martn, Mara Jos Navia, Sacramento Rosell Martnez, Maureen Russo de Rodrguez, Estefana Tocado Orviz, Martina Thorne, and Jovanna Zujevic. I am also grateful to Allison Brice, who was my undergraduate research assistant in the summer of 2012. I also wish to thank Suzanne Rancourt, at the University of Toronto Press, for sharing my enthusiasm about the book from the time I first pitched it to her and for shepherding it into print.

Heartfelt thanks go to friends and family whose hospitality and company was invaluable during my travels to libraries in England, France, Switzerland, Spain, and the United States: Vivian and Roger Cruise, Nick Francomano, Borja Ibarz, Mara Ibarz, Lola Lpez Ibarz, Tanya, Steve, Jackson, and Lucy Schlemmer, and Harriet Welch. Above and beyond their unflagging support, I thank my mother, Nina Rulon-Miller, the comma queen, for her willingness to read drafts, and my father, Frank Francomano, for his help with sixteenth-century Italian. There is no way to thank Eugenio and Pablo enough for their patience, encouragement, and readiness to travel with me. Nor can I thank Eugenio enough for reading every page I have written.

Parts of and the conclusion first appeared in Reversing the Tapestry: Prison of Love in Text, Image, and Textile, Renaissance Quarterly 64, no. 4 (2011). I am grateful to the British Library, the Fondation Bodmer Library, and the Hispanic Society of America for allowing me to reproduce images from their collections in this book without permissions fees.

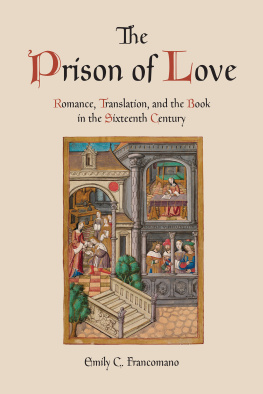

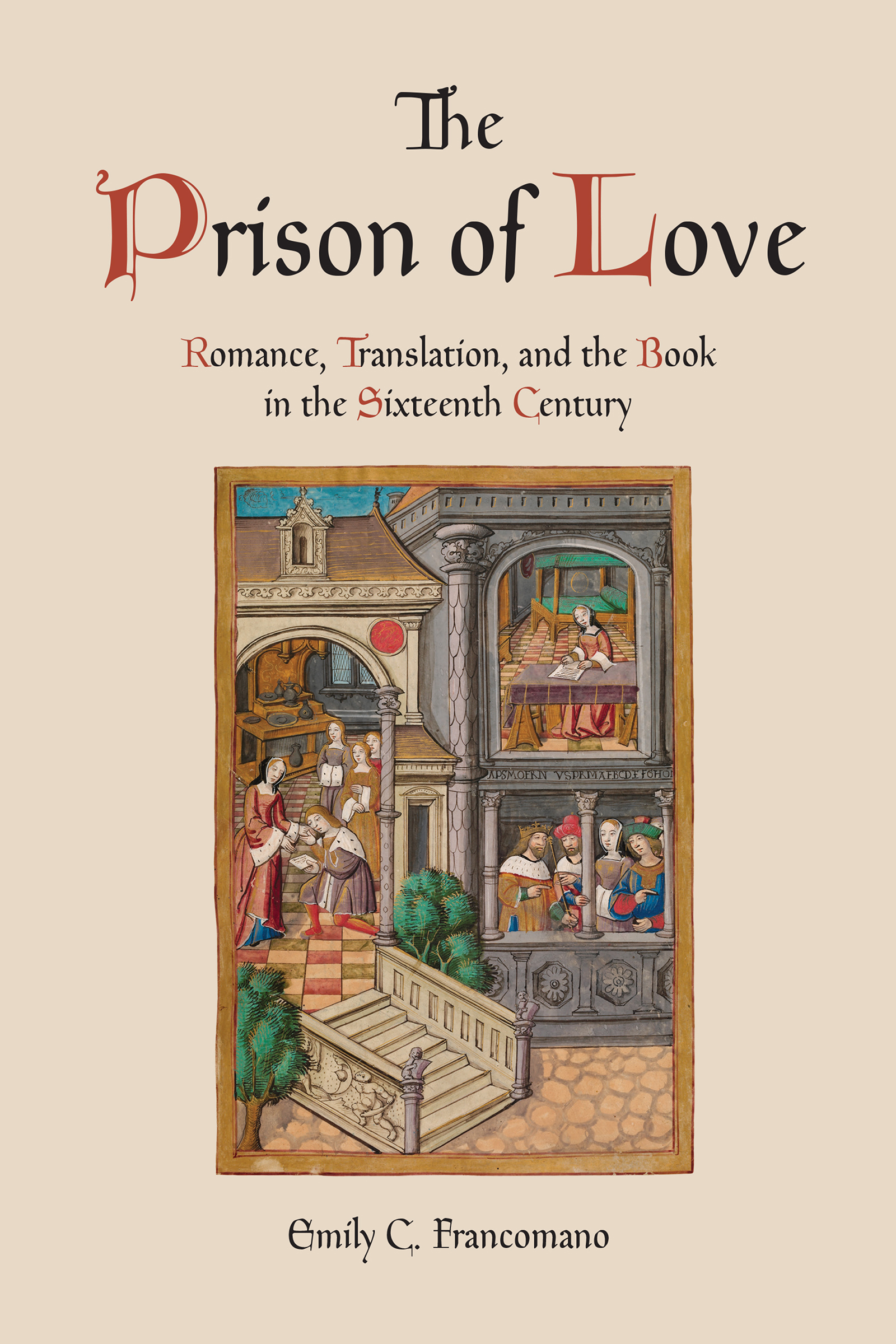

THE PRISON OF LOVE

Introduction: A book that could not be read in peace

Aquella Crcel de Amor

que ass me plugo ordenar,

qu propia para amador,

qu dulce para sabor,

qu salsa para pecar!

Y como la obra tal

no tuvo en leerse calma,

he sentido por mi mal

cun enemiga mortal

fue la lengua para el alma.

[That Prison of Love / it pleased me to so compose, / how fitting for a lover, / how sweet to the taste, / what a sinners sauce! / And, since that work / could not be read in peace, / I have felt, for my sins, / just what a mortal enemy / was my tongue for the soul.]

In the late 1490s, the Castilian author and courtier Diego de San Pedro submitted his works to a poetic inquisitorial review, lamenting the danger that his romance, Crcel de Amor (The Prison of Love), posed for readers. His self-recrimination, be it sincere or not, aptly captures the fervour with which readers in Spain and across Europe took up this work that, as he wrote, no tuvo en leerse calma (could not be read in peace). First composed in the 1480s for the entertainment of the Castilian elite in the Court of the Catholic Monarchs, Crcel de Amor was printed in Seville in 1492. After Crcel de Amors appearance in print, multiple Spanish editions and a Catalan translation by Bernad Vallmanya soon followed. From 1496 on, Crcel de Amor was printed

Taken together, these editions form a strikingly diverse array of printed formats including elegant and illustrated prestige editions, tiny pocketbooks, and Spanish-French bilingual editions advertised as language-learning aids. But the romances sixteenth-century media presence was not limited to print. The Prison of Love was read in manuscripts, some hastily copied, others produced as luxury items and richly illuminated. The romance also appeared as a three-dimensional visual narrative in sumptuous tapestry sets created for the French nobility. Indeed, at the end of the fifteenth century when he wrote to repent of its ill effects, Diego de San Pedro had only seen the very beginning of that

Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable-based inks.

Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable-based inks.