Table of Contents

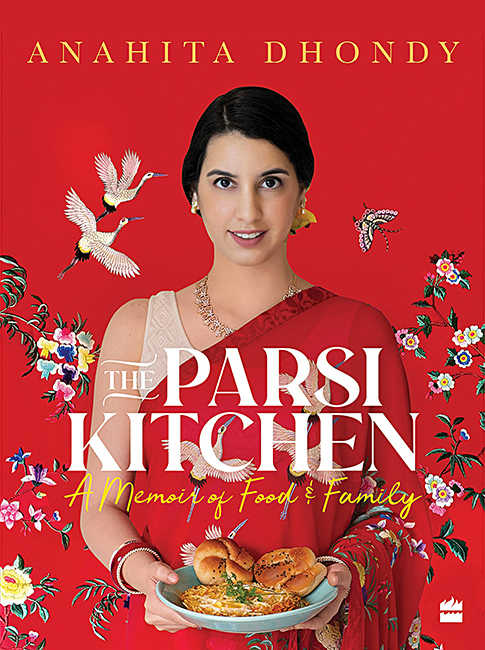

To the strong women in my life

Contents

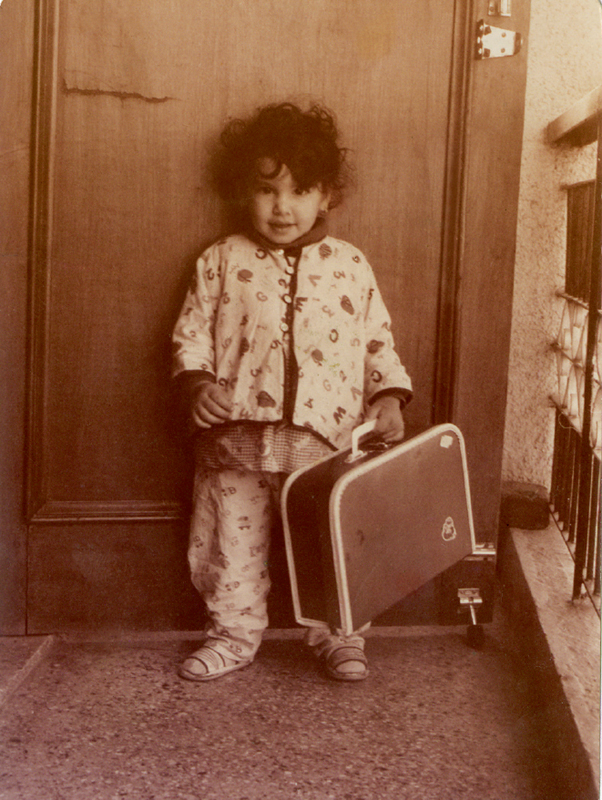

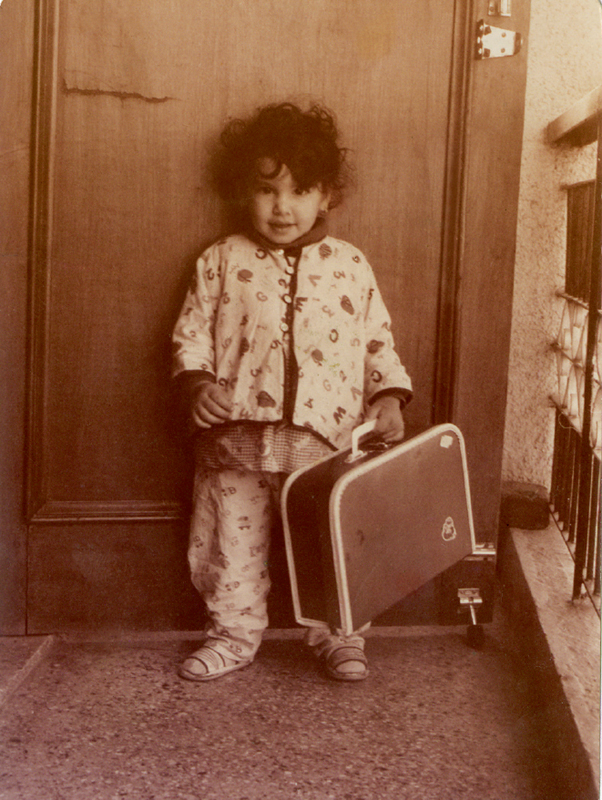

ONE OF MY MOST VIVID MEMORIES is of sitting, cross-legged, on the floor of my mothers kitchen, licking cake batter from a bowl. I was maybe five or six years old, but that was where it all began.

Growing up, I spent almost every free moment in the kitchen, helping out and asking questions. My mother, Nilufer, saw that I had a passion for food and encouraged me to experiment. By the age of eleven, I was icing all the cakes she baked for her home business.

When I turned twelve, I knew that I wanted to be a professional chef and my parents urged me to pursue whatever I was interested in. In class ten, we took a family trip to Aurangabad and along with the Ajanta and Ellora caves, made a sightseeing detour to the Institute of Hotel Management (IHM), where I eventually enrolled.

Ask any eager culinary student and they will tell you that world cuisine is what excites them. Everyone wants to make the most creative sushis and experimental flat breads. Indian food is just shoved to the side. I mean, whos going to study it?

In London, at Le Cordon Bleu (LCB), I had an epiphany. My classmates came from all over of the world, but the one thing they had in common was how proud they were of their ethnicity. It was evident from the respect they showed their traditional food; they revered it. And then there was me: a budding chef who was dismissive of Indian food. I loved to eat it, but I didnt want to cook it.

Until an incident with a pork dish which got me thinking about my own regional cuisine in a way that I never did when I was at home. How strong the flavours are, how complicated the masalas, how ancient the techniques! I asked myself, why am I chasing all these global cuisines when I can do so much with the food back home?

I came back to India, disheartened that I couldnt get a job because of my visa status. My father, Navroze, said, When one door closes, another opens.

And I met ace restauranteur AD Singh. What was meant to be a one-hour conversation stretched to four as we spoke about his to-be-launched project, SodaBottleOpenerWala (SBOW), Parsi food and culture. I was excited because it seemed like a chance to learn more about my roots.

Its been eight years since I made that pivotal decision to take the plunge with Parsi food, and every year I have evolved both as a chef and as a person. Ive had the freedom to create, and discover so much about my cuisine, heritage and indigenous ingredients. Ive learnt to appreciate Indian food and advocate a place for it among the best in the world. From speaking at a summit to mark United Nations Week in New York to representing India at the Chefs Manifesto in Stockholm, Ive been blessed with so many opportunities.

Making the Forbes Asia 30 Under 30 list in 2019 was a huge accomplishment, but what thrilled me even more was that I had the chance to cook for three hundred guests who attended the event.

To think, at age 15, all I wanted was to be a pastry chef!

Who I am is where I come from, so I knew that if I ever wrote a book, Id want to give readers a peek into everyday life in a Parsi household. A bit of bickering, some amazing anecdotes and, of course, classic recipes handed down through the generations. I hope to take you to a place where you get a glimpse of Parsi culture, my family and my roots, and everything that Ive learnt along the way.

Enjoy the journey!

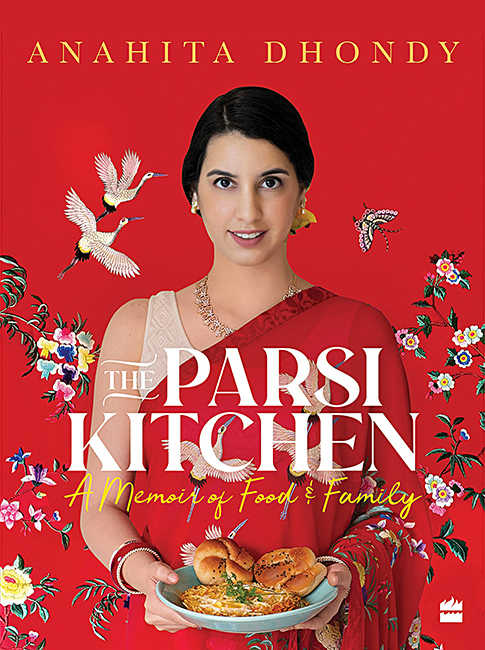

ANAHITA DHONDY

THERES AN AMAZING STORY that every Parsi child has heard from their grandparents or parents, a tale that explains why our community was quick to absorb local practices and traditions on settling in India. An age-old favourite called Milk and Sugar, it describes how the Zoroastrians arrived in India and goes a little like this.

When the Parsis first landed in Sanjan, Gujarat, they were met by the local ruler Jadi Rana. Alarmed by the influx of foreigners, Jadi Rana invited my people to make a case for being allowed to enter his province. Legend has it that he used a silver bowl filled to the brim with milk to symbolize how crowded his lands already were, to make it clear that there was no room for newcomers. The Zoroastrian elders added a pinch of sugar to the milk and said, The way the milk has not overflowed, but been sweetened, we too will mingle with you and add sweetness to your lives.

Wisdom won the day, and the Hindu ruler granted permission to the foreigners to settle and practice their faith.

But the license to settle was not unconditional, and the Zoroastrian high priest was asked to explain his faith to the gracious ruler.

The Kisseh-i-Sanjan by Dastur Bahman Kaikobad, one of the earliest accounts of the Parsi arrival in India, refers to the conditions Jadi Rana laid down before our ancestors. The foreigners would learn to speak the local tongue (Gujarati). The women would eschew their traditional Persian attire for the Gujarati-style saree drape. The men would give up their arms and swear fealty to the ruler and his successors. There was no talk of conversion, as both Hindus and Zoroastrians believed in the right to practice a faith of ones choice.

Thereafter, the Zoroastrians came to be known as Parsis, a term derived from the last port in Persia that they came fromPars. And honouring this sweet story of assimilation is a classic Parsi milk and sugar dessert called Ravo.

IF YOU FLIP THROUGH a Parsi cookbook, you will see a lot of attention given to fish, chicken, meat, rice, eggs and vegetables. Then there are pickles, chutneys, preserves and relishes. The sweet dish section is smaller, and that is because the Parsi repertoire of desserts is so limited. Most of them are adapted from British dishes like puddings, custards, cakes and cookies. Many are also inspired by traditional Indian sweets; Dar Ni Pori, for instance, is a thicker derivation of a Puran Poli while Badam Pak is similar to Badam Barfi.

Ravo, on the other hand, can be called a purely Parsi dessert because its inspired by the story of sugar in milk. A little bowl of goodness, its a dish prepared on auspicious occasions. Ravo made birthdays, anniversaries and festivals more special. Even after Arush and I got married, Ive continued the tradition of making Ravo to mark the Parsi New Years. I dont make it on my birthday, though, because Mom still does.