2019 University of South Carolina

Published by the University of South Carolina Press

Columbia, South Carolina 29208

www.sc.edu/uscpress

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/

ISBN 978-1-61117-996-5 (hardback)

ISBN 978-1-61117-997-2 (ebook)

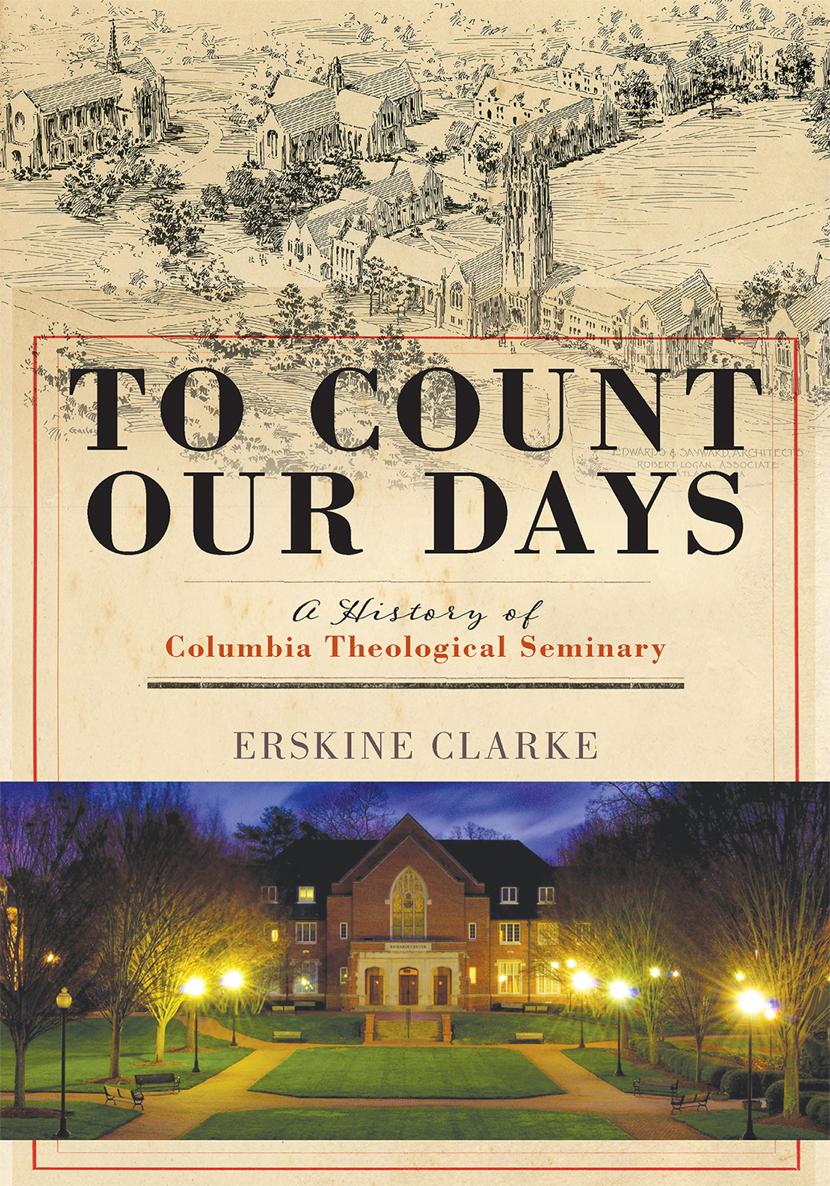

FRONT COVER ILLUSTRATIONS

top, architectural plans for the Decatur, GA, campus;

bottom, J. McDowell Richards Student Center,

Columbia Theological University, Decatur

Front cover design by Adam B. Bohannon

PREFACE

Institutional histories can invite a yawn. They are important for specialists and for those with a personal interest in a specific institution, but as a category of historical writing they do not evoke an imagine of a page-turning narrative. Yet institutions have cultures with their own rituals and character, and they reflect in their own internal life larger historical developments. And institutions, perhaps especially smaller institutions, have within them individual players with their own histories and commitments, quirks and oddities, and those individuals not only help to shape the institutions life but also bring the complexities and mysteries of the human personality to the story of an institutions history. Moreover when an institution exists over many generations, its history is an unfolding story of tension between continuities and change, between remembered ways and practices and the demands of new social and cultural contexts. At least all this has been true for Columbia Theological Seminary.

For the author this has meant that as I studied the seminarys history I became increasingly fascinated by itby Columbias distinctive and peculiar character, by the personalities of the major players and their eccentricities, and by the ways its history tells a larger story of the American South and of religion in the United States. To be sure, I have a personal interest in Columbia as a graduate and as a longtime member of its faculty. But I hope that others without such personal connections will find in the history of Columbia a story that intrigues and that helps to inform their understanding of southern history with all its ironies and of the religious life of the American people with all its complex intermingling of peoples and traditions, of light and deep shadows.

The story of the seminary emerges from the antebellum world of the American South and begins to unfold in an antebellum mansion in Columbia, South Carolina, across the street from the home of Wade Hampton, the Souths largest slave owner. In and around this particular place a brilliant and conflicted cluster of white Presbyterian intellectuals gathered, and from that place they exerted an extraordinary influence on the culture and religious thought of the white South. They included theologians and educators, political leaders and scientists, reformers (the kind white southerners could tolerate) and lovers of a southern home and homeland. With them were wives who were helping to shape in their own ways the male-dominated culture of Columbia and who were quickly becoming a part of dense networks of closely connected families. There among them as well in that particular place were black men and women, enslaved servants, who cleaned houses, cooked meals, and stood beside dinner tables listening to the conversations of white Presbyterian professors and students as they discussed religion and politics and related the latest news of personal interest. Meanwhile on distant plantations black men and women, people with names and distinct personalities and histories, were providing in their labors and in their very bodies the wealth that made the seminary possible.

To this place came students from all over the country and from the nations most prestigious colleges. Most who graduated after three years of Greek and Hebrew, of Latin texts and of dense histories by German scholars, went out to a southern world intent on building what they called our southern Zion not only on the established eastern seaboard but also in what they regarded as the howling wildernesses of south Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. They were to be gentlemen theologians, Presbyterian bearers of civility and a paternalistic tradition and of a Carolina culture by which they meant the ways and social institutions of the South Carolina and Georgia lowcountry, of Charleston and Savannah and their hinterlands of rice and sea island cotton plantations. They sought to be prudent and moderate menthose who avoided the dangers of extremes as they navigated between rationalists and revivalists and between proslavery radicals and abolitionists. But when they discovered in 1860 that they had to make a choice between slavery and freedom, they abandoned their much-vaulted moderation and with unrestrained wrath cast their lot with slavery and their southern homeland.

When Shermans army left Columbia a burned and smoldering city, the seminary campuswhich had escaped the firesbecame a refuge for city residents and for frightened survivors of a ravaged countryside. During the coming years the seminary was to be a refuge for white southerners in other ways as well. From the campus and its professors came attempts to explain the ways of God in allowing such massive destruction and death and to explain how God could allow a corrupt and oppressive North to be victorious in its fight against a righteous South defending its independence and property rights. The seminary was also to become a refuge, a Presbyterian bastion, against the assaults of the modern world and a rising industrial capitalism with its radical individualism. An ideological wallcomposed largely of the phraseology of the past, the language and remembered history of the white South and Presbyterian orthodoxywas constructed to keep out the infidelity and chaos of modernity and to protect a southern way of life.

When an apparent threat to orthodoxy and a white South appeared within the seminary in the guise of Darwinism, a fierce internal war ensued. Forty years before the famous Scopes monkey trial in Dayton, Tennessee, an intellectually rigorous debate broke out on the Columbia campus in the 1880s over evolution and over the concept of development not only in biology but also in human cultureincluding religion. While the conclusions were ambiguous, the debate left the seminary with its horizons narrowed and its world constricted. A comfortable and genteel mediocrity settled over the seminary as it became as intellectually impoverished as it was financially poor. In this it reflected the realities of its constituency in the Southeast and the social and intellectual climate in the little city of Columbia and at its University of South Carolina.

Remarkably seminary graduates from this period included not only those who were serious and faithful pastors but also some of genuine distinction including Rhodes Scholars and those who played important roles in defense of human rights in distant lands. Nevertheless a comfortable and tightly knit mediocrity marked the seminary during the last years of the nineteenth and the early years of the twentieth centuries. And closely tied to that intellectual mediocrity was ideological support for a white South where blacks were kept in their place. That place on the Columbia campus and in faculty homes was largely behind the scenes where food was cooked and rooms were cleaned. And from such a place in the shadows, black men and women, even as they went about their work and their lives, observed and listened to preoccupied white Presbyterians.