The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2016 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2016.

Printed in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-39719-1 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-39722-1 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-39736-8 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226397368.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sylvanus, Nina, author.

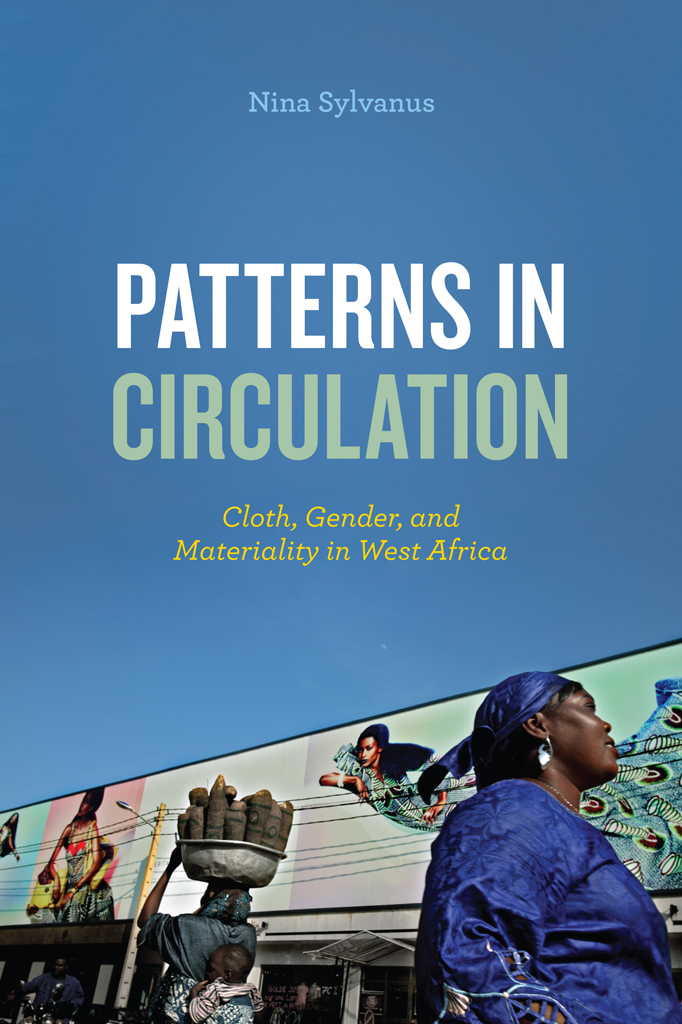

Title: Patterns in circulation : cloth, gender, and materiality in West Africa / Nina Sylvanus.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016017205 | ISBN 9780226397191 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226397221 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226397368 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Textile industryTogo. | Women textile designersTogo. | Textile fabricsTogo. | Clothing and dressTogo. | TogoPolitics and government.

Classification: LCC HD9868.T6 S95 2016 | DDC 338.4/767702dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016017205

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

For my father, Bernd, and in memory of my mother, Renate.

The market I stepped into on my first fieldwork stint during the summer of the new millennium was a confusing and contradictory one. Prior to my arrival in Lom (Togo), I had visited the headquarters of wax-print textile giant Vlisco in the Netherlands, which arranged my introduction to Fabrice Ruiz, the Togolese director of the Vlisco Africa Company (VAC). A former member of the French military, Ruiz ran the Lom subsidiary with an authoritarian handa forceful style I naively assumed had disappeared with French colonialism. His assistant, Livingstone Agbobli, like many Togolese employees and traders in the market, resented Ruiz and his neocolonial style. Agbobli later told me that surely the Dutch considered this type of character to be required in a place like Togo. Furthermore, in the aftermath of the companys restructurings, Agbobli conjectured, They probably needed someone like him to deal with the women. When I asked him to explain what he meant by this, he responded in a slightly amused way, Well, you know, our women are strong-headed, they are powerful!

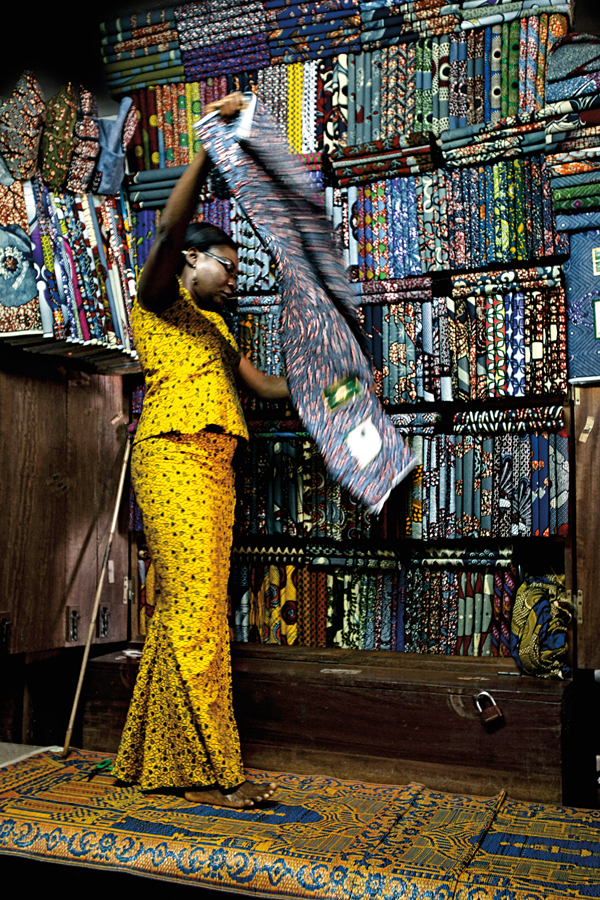

Prosper, an employee at the VAC warehouse, took me on one of my first trips to the famous cloth market, Le Grand March de Lom or Assigam (which translates as womens place). It was there I first encountered one of the powerful women Agbobli had mentioned. The director had instructed Prosper to accompany me through the market labyrinth to visit the shop of Dd Evelyne Trenou, a wholesale trader and VAC client.Benz and their daughters. The term Nana Benz refers to the powerful Togolese cloth traders of the 1950s to 1990s who controlled the West African wax cloth trade until political crisis and global shifts in production derailed their hold on the economy. One of the most potent economic and political forces in Togo for decades, the Nana Benz legendarily defined the nation through their vehicular power when they lent their Mercedes-Benz (hence the name) cars to the postcolonial state.

Ha! There are only Nana 2Chevaux today, Dd laughed, amused by her reference to the small two-horsepower Citron car. Theres no money to be made in this market. Look around you, the market is dead!

I glanced out the window at the lively scene. Why is the market dead? I asked.

Before, every day the market was full. On Mondays the Ghanaians came, on Tuesday cest Cte dIvoire, Wednesday, Benin... Nigeria, and Congo on Thursdays, also Cinquass and Niger and Burkina on Fridays. Everyone came to Lom to get our cloth! she replied, exhilarated at the memories alone.

What happened, and where do all these traders get their cloth from now if they dont come here anymore? I inquired.

Ha! she sighed and turned to the counter, where she pulled out several cloth samples. I looked through the different samples as she continued, You see this design here? They call it Fish Scale in Nigeria (see ). These are classic Igbo colorsred, black, and gold. I used to own this design. In fact, I inherited it from my mother! Its a very old pattern. My mother, you know her father was Yoruba, so she specialized in the Nigerian market. She spoke several Nigerian languages. She owned several Igbo, Yoruba, and Hausa designsand the Igbo especially, they dont like changing color or pattern, each year they come and will buy the same cloth over and over again. But they took it away!

Who took your designs? I asked, surprised by her peculiar reference to design and product ownership. Vlisco, she shot back, its in Cotonou now; we only get the leftovers! Dd and her peers had indeed recently lost control over the distribution of so-called classic designs whose prestige and value the Nana Benz had built and made fortunes from. Vliscos classics are designs that have been in print for more than sixty years, and they make up a large portion of the Dutch companys sales today. The leftovers to which Dd referred were patterns and hues for the Ghanaian and Ivoirian market as well as the new designs Vlisco launches at regular fashion intervals.

Over the next couple of weeks, I met the majority of the cloth traders. The women spoke of their struggles and kept referring to the market in the past tense. One day, to my surprise, a trader invited me to her two-story villa to attend a major market transaction, which cloth traders call une vente (a sale). The merchandise she had ordered from the Netherlands two months before at VAC had finally arrivedand so had her clients. About ten women, covered from head to toe in colorful wax cloth, sat on opulent leather couches and chairs in front of a big-screen television in her living room. I watched a wealthy trader from Kinshasa pull out $50,000 in large bills from a black plastic bag. Indeed, the spectacular amounts of cash that were exchanged on this day made me doubt the traders previous complaints about the dead market. For several hours, I observed these women counting and recounting money and making calls on their cell phones. A group of three Ivoirian women arrived next. Soon after speaking to the hosting trader, they tabled large sums of money from Gucci handbags. The transactions were punctuated by moments of waiting, with snacks served by the traders domestic workers. La vente lasted many hours; the three women from Abidjan stayed overnight, catching the next days flight back to Cte dIvoire.

A decade later, Dds concerns about her shrinking business were unquestionably real. Although she was still a top-tier wholesaler, the markets material and spatial composition had changed profoundly. In the past, she had worked exclusively in wholesale. By 2010, however, she was also selling cloth by the piece (a twelve-yard lengthenough for two outfitsis the wholesale trades standard measure). It was only on rare occasions that she could transact the kinds of volume she had traded a decade earlier, when each of her clients bought between one hundred and three hundred pieces. I walked into her store one day just as an employee was cutting a piece of Dutch wax in half upon a customers request for a

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).