Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by Jim Lampos and Michaelle Pearson

All rights reserved

E-Book year 2020

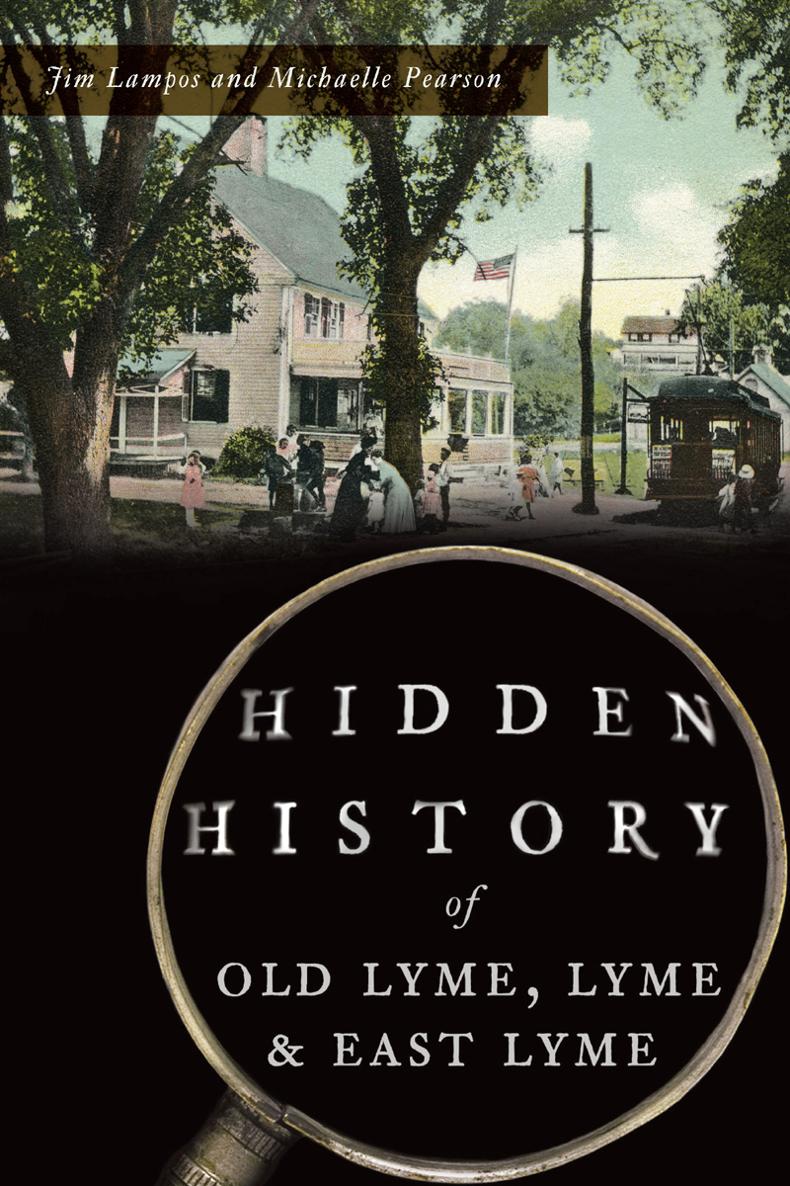

Cover: Ye Golden Spur Inn, Ye Golden Spur Park, on the New London and East Lyme Street Railway. Elizabeth Kuchta collection.

First published 2020

ISBN 978.1.4396.6999.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020930487

Print Edition 978.1.4671.4340.0

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To our children, Phoebe and Silvanos, with love.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

You dont have to listen very hardthe land itself prompts questions: whys that there? Whats this all about? We see things in our daily commute that remain with us as lingering curiosities, which in the rush and thrum of making a buck and living our lives, we often dont have time to explore. I guess thats why we write history booksits an excuse to investigate. Its permission to stop time, borrow a minute to sneak off the highway and check out that old dam, that pile of stones, that weird crook in the road or that impossibly old tree. The funny thing is, they all have stories to tell. And their stories are ours. The land made decisions for us long agohow we made our living, how we made our way to-and-fro. And we, in turn, made our mark on the land. The choices of our illustrious predecessors, to a great extent, still guide our steps today. We are under the sway of their thoughts; we travel their routes; we repurpose their constructions. As the land made them and they made their mark on the landscape, so, too, do we engage with themand in this dance of the past and present, we create the future. This book is dedicated to the hope of an enlightened journey in the days to come.

A NOTE ON PLACE NAMES AND LANGUAGE

For those unfamiliar with the area, all this talk about the Lymes may be a bit confusing. Todays Old Lyme, East Lyme and Lyme were once one town called Lyme, a political entity that corresponded to the Lyme parish of the Congregational church. As the population grew in the eighteenth century, a second parish, or society, was established in the eastern portion of town, with another in the north part of town. In the nineteenth century, these three societies each became their own towns. The second society became the town of East Lyme in 1839, and the first society and north society became the towns of Old Lyme and Lyme, respectively. Today, while the three towns have a shared identity, each also retains its own unique character. Lyme is the most rural, maintaining its agrarian tradition. Old Lyme remains a traditional New England hamlet, while East Lyme has embraced modern development.

Adding to the confusion are the villages within each town, some of which have a more defined character than the town itself. Niantic, in East Lyme, is a good example. Today, it is known as a seaside community of charming cottages and shops, though its identity as a distinct entity goes back to Algonquin times, as it was the center of the Nehantic tribe. Flanders, also in East Lyme, has an entirely different character. In the nineteenth century, it was home to a thriving group of mills, and it remains a commercial district today, though the mills have been replaced by strip malls. Similarly, some neighborhoods in Old Lyme and Lyme maintain their own special character, such as Lymes Hamburg section or Silltown in Old Lyme. Confusing though these distinctions may be, they are part and parcel of the quirkiness that makes the Lymes so alluring.

As we discuss the various parts of these towns, we may use place names anachronistically; we may, for example, refer to Old Lyme in 1750, when in fact no such town existed. It was simply called Lyme. This was done for the sake of clarity, so the reader may understand where a place would be located in the modern landscape.

Similarly, the reader will notice some nonstandard spellings or word usage in quotes from early town records, letters and memorials. We have chosen to retain the idiosyncratic spelling of these original documents to convey the flavor of the language at the time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the following organizations for their kind assistance:

Connecticut Historical Society

Connecticut River Museum

Connecticut Spiritualist Camp Meeting Association

Connecticut State Library

East Lyme Historical Society

East Lyme Library

East Lyme Town Hall

Indian and Colonial Research Center

Lyme Grange No. 147

Lyme Public Hall and Local History Archives

Lyme Public Library

Lyme Town Hall

New York Public Library

Old Lyme Historical Society

Old Lyme Phoebe Griffin Noyes Library

University of Connecticut Library, Thomas J. Dodd Research Center Archives and Special Collections

With special thanks to Linda Alexander, Arthur Skip Beebe, Nancy Beebe, Carolyn Bacdayan, Tara Borden, George Carfi, Maureen Caswell, Sandra Downing, Baylee Drown, Katie Huffman, Ellis Jewett, Elizabeth Kuchta, Mark Lander, Eric Lehman, Marcus Mason Maronn, Dani McGrath, James Meehan, Alison Mitchell, Amy Nawrocki, Mary Jo Nosal, John Pfeiffer, John Pote, Cathy Shields, Laura Smith and Abigail Stokes.

THE BURYING GROUND

The dead tell no tales, it is said, and perhaps thats true. But their gravestones do, and on a morning when the fog hangs low, swirling like a wraith among the sandstones, granites and slates, a curious explorer in the Duck River Cemetery, along the banks of the river that lends its name, will be rewarded with true tales and fanciful myths told from the earliest mists of Lymes history. These are the stories we have told ourselves for three centuries and more and that mold who we are as citizens of this seacoast town.

On Memorial Day, all and sundry march down Lyme Street, following flags, fire trucks, fife and drums corps and schoolchildren into the cemetery, where they will honor dead and living veterans and hear fine speeches from venerable neighbors and luminaries. The ceremony will end with a three-round salute, fired amid gravestones dating to the seventeenth century, and thus the living will commune with the dead and honor them, as the departed live among us stillthe legacy of their deeds forming and informing our world.

It seems fitting and proper that the founding myth of a New England town of considerable antiquity should concern a vow to preserve and protect the grave and memory of a beautiful, red-haired lady and, in exchange, a considerable estate would be granted. Such is the case with the founding of Lyme. Matthew Griswold was given his estate, Black Hall, at the mouth of the Connecticut River in exchange for a promise to perpetually care for the grave of Lady Fenwick. This legend has more than a grain of truth to it, as Griswold is known as one of Connecticuts early gravestone carvers, who not only fashioned Lady Fenwicks table stone in Saybrook but also carved those of the colonys earliest founders, which can still be found at the Ancient Burying Ground in Hartford. Now in their twelfth generation, the direct descendants of the first Matthew Griswold still reside at Black Hall and maintain Lady Fenwicks grave and keep her memory, as promised.